After a couple weeks attempting to convince people to edit and finding out through reduced traffic that no one really wants to do it (could have told myself that one), I have decided it’s time to branch out towards more general writing once more. Reading the work of several aspiring and new writers, I’ve found that one of the big problems with a lot of writing today is how often people strive to meet certain criteria without understanding the criteria.

It’s a problem that haunts many. So today I’m going to tackle a set of character archetypes that it seems almost everyone stumbles on once or twice and try to decipher just why they fail.

1. “Underdogs”

What you’re trying to do:

Inspiring, sympathetic characters that capture the struggle of the common man – the underdog is the symbol of every average person that ever had to try to take on a bigger, more powerful challenge. Everyone in the world feels overwhelmed about something eventually. So of course you want to have a character people can relate to who is facing something just as overwhelming as what a person would face in the real world.

The underdog is a vital part of literature because it is the person that readers can most relate to. In fact, they would be the insertion point for just about everyone in your audience. How could that possibly go wrong?

What you actually do:

People often mistake all “misfits” to be “underdogs” and thus put those “misfits” in the underdog role by default without considering whether or not the misfit actually…fits.

Your character isn’t an underdog if the thing that is stopping them happens to be a personal defect they have control over. In other words, your character isn’t the underdog unless someone else is stepping on their neck. Wayne from Wayne’s World wasn’t the scrappy underdog, he was a satirical piece reflecting the absurdity of Generation X thinking they were disadvantaged. They weren’t, they were incredibly advantaged and were just jaded and looking for something to complain about. Your character can’t be jaded or shiftless unless there’s something for them to be jaded or shiftless about.

In Wayne’s World, despite the fact his antagonist is usually better connected and wealthier, Wayne’s still a flake. Think about it, why did Wayne almost lose in both of those movies? Did the other guy actually do anything to put him down or did he do it to himself? In both of the movies, he did it to himself. He made an ass out of himself to the girl that was willing to see beyond his flaws…twice.

How to fix it:

Make the opposition bigger.

No, seriously, you don’t need to make your character worse to make them the underdog, you just need to scale up their opposition. Case in point is Batman up there. Batman, Bruce Wayne, is a billionaire with vast resources at his disposal, superb physical conditioning and years of training in martial arts. As a part of the 1%, Bruce is pretty firmly not the underdog in any real world context. But as you see above, when fighting a god, Bruce Wayne is suddenly not the big dog in the fight.

That is the point of the underdog, not the claim of oppression, the actual act of being overwhelmed and still coming out on top.

2. “Well-Rounded Characters”

What you’re trying to do:

You want your character to be likeable, so they’re going to have to have a lot of likeable traits. You’re going to want to make them the outdoorsy type, but still nerdy, you’ll want to give them a cultured side, but not so cultured that they don’t happen to alienate people. You want to make them kind, compassionate, insightful. You want to make them just all around well balanced and capable of winning the hearts and minds of everyone.

What you actually do:

And you will name him or her “Mary Sue” or “Gary Stu”. And he or she will be the most perfect person of all time and will be beloved by all except for those select few haters who just don’t understand the depth of what you’ve written for this world! Then someone will sneak up on you and try to strangle you as you giggle uncontrollably at the pencil sketches you’ve made of Gary while gingerly stroking it and calling it your precious.

How to fix it:

When you’re trying to build a well-rounded character, you’re not actually trying to make them the jack of all trades, you’re trying to make them more human.

The problem is that “well-rounded” is actually a poor descriptor of what you want to make. The truth is that realistic characters are actually jagged and uneven. Realistic characters have flaws and rough spots. The most classic characters ever weren’t the perfect characters, they were the imperfect ones that reflected some of the insecurities and imperfections of the audience.

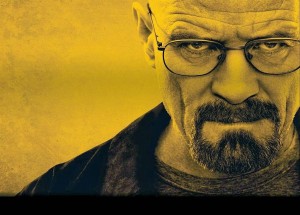

A recent example is Breaking Bad, a show that gripped people so effectively that there was an outcry over people possibly spoiling the end to it. And part of the reason was that Walter White, the protagonist of the series, was both sympathetic and incredibly messed up at the same time. People were intrigued by this common, simple man in a horrible situation being drawn into dark places so easily when under pressure.

He was a mess and didn’t know what to do when put under pressure… just like the rest of us.

3. “The Smart Guy/Girl”

What you’re trying to do:

It’s a complicated world with complicated facets that you just have to get a character to explain. This character has to be able to solve the mysteries and explain the things that keep your plot moving along. Maybe you need a hacker to explain how other hackers are controlling the world’s power grid. Maybe you need a forensic scientist to point out that a very special bullet was used to kill your victim. The smart characters make the world go round and you need one now. So why wouldn’t you put one in?

What you actually do:

Unfortunately when you think of “smart” characters you actually think of socially inept and dysfunctional characters who hide in basements and haven’t talked to a member of the opposite sex in a casual conversation in 20 years.

Stereotypes are bad in almost all cases, but for a long time this one was accepted because the mainstream culture was separate from nerd cultures and thought that just acknowledging these people were smart was enough to make them positive figures. But place yourself in their shoes and consider what you’ve just said about people who happen to know how the world works.

- they have poor hygiene

- they’re uncoordinated

- they don’t belong with human beings

- they may look like Gollum wearing a pair of glasses

- they subsist on a diet of Cheetos

- the only human contact they’ve had is when they touch themselves while no one’s looking.

This isn’t going to fly, especially if you’re writing in a genre that happens to have an audience full of these people.

How to fix it:

|

| A little dysfunctional? Yes. But his fans still call themselves “Cumberbitches” |

Try to keep in mind that intelligence and personality are separate aspects of a person. A smart person isn’t necessarily going to be drawn to Dungeons & Dragons or videogames. In fact, the number of well educated and intelligent people in the media is staggering and some of the most successful people in entertainment are actually sporting very challenging degrees.

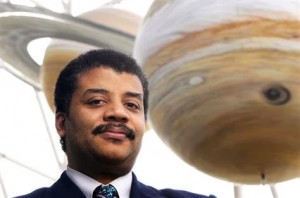

|

| Pictured: Harvard Psychologist, no shit! |

The point is: create a character, a “well-rounded” character (read: messy one), and make one of their traits a higher than average intelligence. Sherlock Holmes did drugs, Indiana Jones is a college professor and Vin Diesel plays Dungeons & Dragons: stereotypes don’t always stick.

4. “The Outcast”

What you’re trying to do:

Humans are a pack animal, we thrive in groups and we struggle to operate when we’re excluded from a group. It’s a deep seated fear that we could be rejected and singled out. Because of this, everyone can see some sympathy for the outcast and the person who is restricted from being a part of the world.

Hell, it even works for reindeer.

What you actually do:

There’s a thin line between an outcast, a misfit, and a whiner or a “poser”. Generally it’s okay for your outcast to be displeased with their position, but you have to make sure that their complaints are measured against just how bad things are for them. If your character is part of an actual group, you can have them complain about their mistreatment, but the more they complain about being isolated the more you risk losing the sympathy of the audience unless you justify their complaints.

The other side of the coin is when you have someone removed from society for no clear reason. If someone is a beautiful person who has everything right with them and no reason for anyone to hate them (see Mary and Gary above), then making them an isolated loner is a bit of a stretch that no one is going to believe. The only way one of these could happen to be believable is if the removal from society is internal rather than external – i.e. if the character has a personality issue that makes their interaction with people difficult.

How to fix it:

Give them something to bitch about. If your character acts as an outcast, they should be depicted as an outcast. You need to keep it reasonable, there needs to be a problem with them that makes their status as an outcast understandable. It’s not enough to simply say no one likes them simply because no one likes them. There must be a reason these people aren’t part of the pack as a whole, whether it be something superficial or deep down.

If they have a reason to feel rejected, it’s okay for them to bring light to it.

5. “Strong Female Protagonists”

What you’re trying to do:

There need to be more female protagonists in just about every genre of fiction, especially speculative fiction genres like SciFi and Fantasy. And the protagonists we do have in the genre are a bit…weak.

So if you want to set a new standard then you’re going to want to make your female protagonist one of the strongest female protagonists that you could ever achieve! Hopefully people will be motivated by your work and change the world. Maybe you’ll create the next Katniss.

What you actually do:

Usually when someone tries to create the strong female protagonist… they hit all four of the previous entries head on like they suddenly forgot everything they ever knew about character development. But don’t worry because even the professionals do this sometimes.

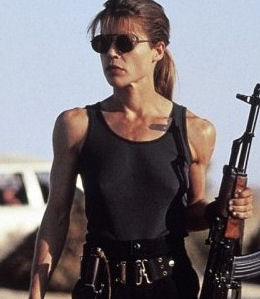

Ellen Ripley’s picture is up here twice for a reason. In the first three Alien movies, Ellen Ripley was pretty much the face of strong female protagonists in science fiction: a normal human woman trapped with an alien beast and overcoming it despite the loss of her crew. In Alien Ressurection, however, she was turned into a god damned half-alien hybrid super-soldier (see: “Underdog” and “Well-Rounded”) with deep personal knowledge of the Xenomorphs (“Smart Girl”) that the rest of the crew were afraid of for no real spoken reason except she was intense and could suddenly dunk (“Outcast”).

The movie was horrible.

But don’t worry, because you know who wrote this? Joss Whedon.

So if you managed to make these mistakes and roll out an unfathomable mess of a Strong Female Protagonist, don’t feel so bad about it. After all, Joss recovered from his mistakes, so can you.

How to fix it:

Apply all of the fixes from the previous four entries on this list and you will have a damn good character to begin with. A great example of this is Sarah Connor, who was facing the threat of human extinction at the hands of killer robots while the rest of society could either choose to stand with her or against her. A lot of people chose to stand against Sarah in her crusade to make sure her son would live to see a better future. But Sarah never gives up and trains herself to become an expert in every skill she needs to be able to pass onto her son so he could someday be the soldier he needs to be.

If you look at her (or any classic strong female protagonist) you’ll find that they have all of the “fixes” designed into them: a strong opposition, flaws, a non-stereotypical personality and a justified disagreement with society.

Some could argue that Sarah is too masculine to be considered a good example of Strong Female Protagonist. I’ve heard people argue that her willingness to resort to violence and her general aggressive personality speaks of men more than women. But there have been a lot of similar instances of female characters in other works going to great lengths to do exactly what Sarah was trying to do.

In fact, if you look carefully, you’ll find even the most unassuming of characters can transform into this figure when given proper motivation. In the end, I’d argue that if you want to see someone who’s willing to kill…

You’ll never find a good mother who wouldn’t protect her child.

(Hopefully, the characters in my books are a good example to follow. If they aren’t, no worries, Joss recovered too. Give them a read and see my potential Whedon-ness)