As of this writing, it’s been about a week and a half since the end of NaNoWriMo and a little over a week before the #Pitchmas event on Twitter. Your editing should be getting along if you listened to me at all last week. But there are some aspects of editing that always gall writers to no end, even after they get that feedback from their readers. How do you know when to keep a scene and when to throw it aside?

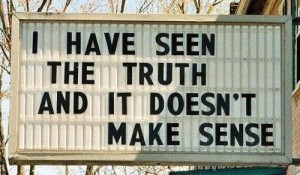

The general rule of thumb by the writing community is William Faulkner’s quote “In writing, you must kill all your darlings”. But William Faulkner’s line being applied to editing is the worst advice that I’ve ever seen and it still confounds me to this day that people keep using it in these conversations. That’s right – the emperor has no clothes, damn it.

The reason why people use this line is because they’re trying to tell you to not be so attached to your work that you ignore the flaws. You may have loved a scene that just doesn’t work anymore. But the advice itself is so vague that it’s basically saying, “delete all the scenes you find likeable and see what you get.”

That’s incredibly stupid.

So when thinking of an alternative to this piece of advice I started to consider just how you would go about determining what scenes to keep and what to throw out. It’s hard to really know for sure what you can and can’t keep because there’s so many factors to consider. But then, my nerd side spoke up and told me: “Hey, Asimov provided a solution to the conflicting functions problem years ago!”

That’s right, I’m going three laws on you guys even though you’re all fleshy humans (for now). In a hundred years, when this blog is found on some lost archive and is viewed again by my future counterparts, they’re likely to be robots anyway.

This is the highest priority for everything you do. When you’re editing and you realize that your scene makes no sense, it may be time to get rid of it. I’m not saying that you should get rid of everything that people don’t “get”. I’m saying that if you ask yourself “what is this scene about?” and your answer is “I don’t know” or “I can’t explain it”, you may need to get rid of it.

This isn’t an effort to dumb down your work, either. The thing about scenes that don’t make sense is that they break your narrative flow. You have to make sure that when people stop to question those plot points that there’s an answer waiting for them somewhere, even if it’s not immediately in front of them. This is especially true of mysteries – it’s perfectly okay if people don’t get it, so long as they get their answer eventually.

Sometimes there are scenes so complex that the audience isn’t going to understand them. Maybe there’s an extra detail of knowledge that isn’t well known to the audience but makes sense of everything in hindsight when you eventually reveal it to them. These are not crimes. It is perfectly okay for the reader not to know what exactly is going on at any given moment so long as you know what is going on. And most importantly, if you’re planning for the long con (a series for example), then you could and should be allowed to leave some scenes in there that don’t make immediate sense to the audience.

The point is, it has to make sense and be explained by the time you’re done, not necessarily as you write it.

This is another key thing to remember. A lot of times you will find, especially if you wrote your manuscript during NaNoWriMo, that there are scenes in your story which you wrote because you were either filling space or began to write it and forgot why you started. This is understandable and sometimes you end up with these completely by accident. But the point here is that your scenes have to have a point of some sort as you write them or decide whether or not to keep them.

However, it’s not as simple as just having a purpose. That purpose has to make sense (like the previous law states). If the purpose doesn’t make sense, then you still may want to consider getting rid of it. If you don’t want to get rid of it then you’re going to have to rewrite it to conform with the first two laws here, give it a purpose (any purpose) and have it make sense.

Once again, this isn’t about whether or not the audience can see that purpose right away. Maybe your purpose is hidden from them or it’s building towards something you plan to do later. These are perfectly okay so long as that purpose exists and that purpose makes sense. If both of these are true, then you keep it as is, unless, of course, it also violates the third law.

The scene must be concise so long as its brevity does not cause a violation of the first two laws

This one is simple and is also incredibly hard to follow through on. Thankfully, a lot of work today has also shown that it’s the least important of the three.

You must keep your scenes flowing quickly. The average reader’s attention span is a valuable and finite commodity that you have to treat with the utmost respect. To maintain their attention you’re going to have to make the story feel like it is running along at a steady pace.

This isn’t about word count, this is about the ease of which a person can get from point A to point B in your story. We’ve all read stories that were short but felt like they went on forever. These stories are violating the third law without even having the length for it. What you have to do as a writer, and an editor, is make sure that your story doesn’t drag. If you can make it read smoother and more naturally, then you’re going to succeed. If you can’t do that, then it’s time to start cutting out the needless bits in favor of something that will do the job without ruining your pace.

Mind you, only do this if cutting the material won’t erase the purpose of the scene or make the scene more confusing. If your cuts make the end result come off looking less natural, even if they read faster, your draft has regressed. If it reads naturally and quickly but in the end has no purpose and/or doesn’t make any sense, your draft has regressed. So this law is to only be applied when you can also manage to follow the other two laws.

It’s a simple, common sense method of moving ahead, even if it’s a little… mechanical.

So you can thank Asimov’s ghost for inspiring this one.

One thought on “The Three Laws of Rob-Edits”

Comments are closed.