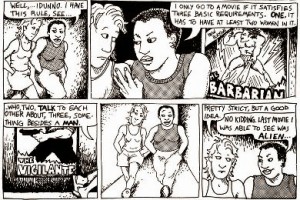

As I stated yesterday, I proudly support equality among all people regardless of their race, creed or gender. But along the way I have had trouble calling myself a “feminist” because there were certain parts of the community that I felt had been too extreme. One of those things is the frequent misuse of something infamously known as the “Bechdel Test”.

In the 1980s, cartoonist Alison Bechdel put forward an observation in her comic strip “Dykes To Watch Out For” that the film industry had failed to treat women fairly in their movies. In the strip, one of her characters says that she wouldn’t watch any movie that didn’t follow three key rules.

Sadly, this has led to many writers, including myself, to become too caught up in trying to figure out ways to make their stories work with this test. A lot of feminists will argue that there’s no real need to hold the Bechdel as an absolute. But from the point of view of someone creating stories, it’s terrifying to think you may have failed it. It’s only after a lot of careful consideration that people like me realize that trying to chase that test is a fool’s errand and a bit damaging to the creative process.

You see, while the Bechdel Test works very well as an observation on the industry, it fails horribly as an actual “Test”. Most moderate feminists have pointed out, quite accurately, that it is not at all a true representation of what would be considered “feminist values”. Often times, horribly sexist depictions can actually pass the test with flying colors while much more positive female characters can fail or nearly fail the test due to one of the rules not passing. Need proof? Consider this:

So what I’d like to show is that the Bechdel test isn’t the end-all, be-all. I’ve found four characters in four movies that fail or nearly fail the Bechdel test who I believe are actually stronger female protagonists than Bella Swan (I know, aiming high). The goal behind this is that I want to show that, even if you feel like you can’t quite pass the Bechdel test, there are other ways of looking at these characters that are just as respectful to women.

The “Mako Mori” Test

The rules according to the Mako Mori test are as follows:

This part here is actually lowering the bar a bit too much, but it passes because the people who proposed it only had two rules and thought this would even out the three rule standard. If I were to be involved in rewriting it, I would have amended it with #1 from the “Ryan Stone” test (see below).

This is incredibly important in movies where there’s only one female character with speaking lines. Mako Mori is essentially the only woman who says anything of value in the course of the entire movie. So it would be incredibly easy for her to be sucked into the story of the male protagonist and not have one of her own. The fact that she does get her own narrative which features so prominently in the movie’s overall plot is something worth giving credit for.

3) That is not about supporting a male character’s arc.

Once again, it would just be so damn easy for her to be sucked into the male character’s arc. Avoiding this in a film that should have easily put her in that position is remarkable and note worthy.

|

| also like to point out, no ass shots on the poster |

The Sarah Connor Test

Consider for a moment that Twilight, a series who’s female protagonist once tried to kill herself so she could imagine her ex-boyfriend, has actually passed the Bechdel test successfully, while Sarah is given a dubious credit due to the fact she rarely talks to anyone that isn’t in a group (a group which tends to include men). Sarah, in Bella’s position, would have killed Edward Cullen for being a threat to the future and buried his ass in an unmarked grave with a cache of guns to be used on him if he ever rises again.

Sadly, Sarah doesn’t pass the Mako Mori test either because her character arc is primarily about protecting her child – a boy. This means that for all intents and purposes, Sarah’s narrative arc supports a male narrative arc, even if that “male” is portrayed by a young Edward Furlong.

|

| Sporting a somewhat feminine haircut |

So for Sarah, I propose these:

1) A female character must have internal motivation.

Sarah’s motivations may be about her son, but they’re entirely her own. Some may argue that Sarah was given her motivations by Kyle Reese in the first movie. But remember for a moment that Kyle wanted specifically to meet Sarah because she had been a legend in his time. Kyle did give her the motivation – by telling her that one day she was going to be so badass she was going to inspire her son and everyone that followed him in the future.

She had a self-fulfilling prophecy of badass.

2) Be proactive without requiring involvement of men.

This here could be seen as a strength or a weakness in her case, but feminist none-the-less. Despite being in an asylum, working with a machine that has knowledge of the future and generally being in a scenario that is controlled by masculine figures – Sarah does whatever the hell she wants to do and in two instances goes completely rogue of her own accord. Stuck in the asylum? Break out. The future is in danger from the work of an engineer? Shoot him dead.

One could argue that she’s a bit too much of a loose cannon. But even Mako Mori had to ask permission.

3) And be competent in its execution.

When Sarah does go rogue, she does it with extreme efficiency. She knows how to get shit done and does things with cunning and skill. In the process of breaking herself out of the asylum, she successfully achieved more steps than should have logically even been possible. And, were it not for the interference of killer machines from the future, she likely would have found her way to freedom regardless.

In fact, in terms of Sarah’s competency, let us remember that John Connor ends up saving the future, a fact entirely credited to Sarah’s mentorship as a child. That means, for all intents and purposes, Sarah saves the future by leaving someone with her knowledge and skills in her place.

And, as a final note, unrelated to the three rules but pointing out just for the sake that I do not want that ugly mark to remain on her record: Sarah Connor does pass the Bechdel test in the Sarah Connor Chronicles series, which was cancelled far too soon and also featured a much better female terminator than Terminator 3.

The Slim Test

For equality’s sake, I think that some of the most positive figures you can find are going to be the figures who start out in a diminished position and then find their footing and fight back regardless. Sarah Connor from the previous entry started out this way in the original Terminator, only to become the dominant figure she was in the second. Mako Mori survived a Kaiju attack and stood up against them again later in life. But characters like “Slim” get abused by a man and suddenly the growth she experiences later isn’t quite as positive as it is in the other cases? That doesn’t feel right to me.

So for Slim, I propose these:

Slim’s entire narrative is about finding her courage and having the will to fight back. When she begins the story she has long hair and very few cares in the world. In fact, in the early acts of the film you could say she was an incredibly shallow person. But by the end of the film she has transformed herself physically and mentally for the sake of ending her torment.

Some have argued that the film romanticizes spousal abuse by making it look like “any woman should be able to fight back if she really wants to”. But that’s not the point of this. The point of this is that Slim does not submit to her treatment and grows in order to get away from it. I feel like that’s something worth acknowledging.

2) While acting in favor of her own needs.

Once again, it would be incredibly easy to make this solely about another character. But in the things she does, Slim is acting for herself and her daughter and no one else. It’s true that in her case she is left with few other options, but once again, that’s not the case for all characters in her situation and the fact she continues to operate for herself and her child is something she, and other characters like her, should be acknowledged for.

And this one, this is the crux. Slim gets the shit kicked out of her time and time again over the course of the movie, terrorized and chased down relentlessly by her abusive ex-husband. In all respects, he is doing everything he can to prevent her from being alive and well without him. How easy would it have been to portray her giving up and being saved by one of the other men in her life? Way too easy for us not to give credit for her standing up for herself.

The Ryan Stone Test

So for her, I propose these:

This probably should have been rule 1 for the Mako Mori test. I don’t think, if you have only one or two female characters, that it’s just enough they exist. I think that if you have one or two female characters they should be prominent in the story to the point that you could make an argument that they are the protagonist like Ryan Stone or deuteragonist (one of two primary characters, potentially a protagonist in their own right, but not necessarily presented as such) like Mako Mori.

Ryan Stone gets a bit emotional over the course of Gravity. In fact, one could say there are parts in the film where she loses her proverbial shit. But here’s the thing, Gravity presents one of the most terrifying experiences that a real person in this world could have. From the moment things went wrong in space, Stone and her companion are utterly screwed. So when she loses her shit, she is not being a fragile little snowflake, she is having an honest moment of realization that she is possibly in the worst situation conceivably possible for someone in her profession. No one would belittle a male character for breaking down and starting to hallucinate, so I won’t belittle her for it either.

Over the course of Gravity there are very few characters, period. She is flying through space in a spacesuit with contact only with one other person at any given time. Because of this, trying to hold her to the two women rule would require Stone be a few miles closer to the ground where there would simply be more people to interact with. And, frankly, I don’t think a character should have to survive re-entry to hold a conversation with another woman to be able to be acknowledged as a positive figure – but that may just be me.

Conclusion

These tests, like the original observation of Alison Bechdel, are not actually meant to be a set of steadfast rules, or even a guide. They’re observations that failing the Bechdel test doesn’t necessarily equate to failing at being a positive figure. For that matter, I think the fact that Twilight passes the test for the entire run despite the actions of Bella goes to show that passing it just simply doesn’t make you a positive feminist role model either.

But here’s the saddest part. For all of the effort to frame that these characters above may actually be better depictions of women than Bella ever was – the tests are still not perfect and never will be. Why do I say that? Because if you look carefully you’ll realize that Twilight still passes several of them without very much rule bending.

And, faced with that, I turn to an underrated wordsmith of our time, a man that has mastered the one true sentence as Hemmingway strived to do. I give to you… Ron Simmons.

Pretty much sums it up.

“Often times, horribly sexist depictions can actually pass the test with flying colors while much more positive female characters can fail or nearly fail the test due to one of the rules not passing.”

EXACTLY my problem with the Bechdel Test: It applies a binary pass/fail judgment to all films regardless of internal context or intent.

A film where a bunch of men abuse and beat the crap out of two women for two hours, but those women have a single conversation about something stereotypical like shoes and babies and shopping: PASS

A film full of several incredibly strong female characters who topple the patriarchy but never interact with each other (or if they do, they talk about their male oppressors)? FAIL.

The best way I’ve found around this is simple: Write complicated, fleshed-out women with the intention of creating interesting characters, not the intention of fulfilling or shoehorning in an agenda. If anyone finds fault with that, they’re doing it wrong.

The truth is, people should be writing well fleshed out characters in general. But one thing that I’ve seen happen often is that a lot of people who are just starting as a writer look towards guidelines and a structural backbone to show them what to do. Too often, this leads them in the exact wrong direction.

One example I remember was when a not so decent writer was asking for help from a much more skilled writer and that skilled writer pointed them out to look into the Hero’s Journey. To the skilled writer, this was just pointing out a new piece of research that was going to give them an idea of how other stories have been structured and what that says about writing in general. But the inexperienced writer? They tried to duplicate it almost exactly like a checklist.

That’s really where the worst damage is done, new writers learn how to do things wrong because they’re so concerned about the structure and then they never grow past it. Bechdel, Hero’s Journey, the three act structure (which actually tends to break down into many more acts when you look closer): these are all meant to be research, but people take it far too literally.

That’s why I made sure at the end to go “this is NOT a metric and they STILL fail when applied to a bad character”. Because I’m fairly sure that if I hadn’t, someone out there would have used them like that. Frankly, they still might.