There’s a lot of pros and cons to being an Indie. On the plus side, you can determine your own fate and you can be at the helm for every major decision. On the other hand, you don’t have the benefit of the advice given to the traditionally published authors as they go through the process of entering the market. You don’t have an editor, a publisher, a publicist and an agent to tell you what’s the “right” and “wrong” of your work as you go out into the world. And for some people that can be terrifying, especially as we enter a time when independent works are so easily adapted into more mainstream formats. It is possible, today, that an independent author could have their work adapted into a film or something to that effect. And because of that, it’s hard to look at certain debates and not be concerned about what your role is in it all.

Last week, I talked about a recent article about Elysium and the fact that a lot of modern science fiction movies spend a great deal of time focusing on action and other elements of their plot in order to make it more mainstream. While I didn’t agree with the idea that these features made Elysium and movies less “sci-fi” than more quiet films, I did see one point in the article that I felt was really worth considering. Agree or disagree, violence is a large part of our culture and the artwork our culture creates. And because of that, there’s a constant debate over the idea that the violence may be contributing one way or the other. As a traditionally published author you would have a lot of voices to give you helpful advice, but on your own? Not likely.

What is your responsibility? It’s a question so haunting that the professionals tackle with it constantly. Some of them argue to one side, some of them argue to the next. Hell, the pilot episode of Castle opened with the concept as the lead character Richard Castle was suddenly involved in the investigation of murders that perfectly mirrored his novels.

|

| Sadly, this fictional author has sold more books than me in the real world. |

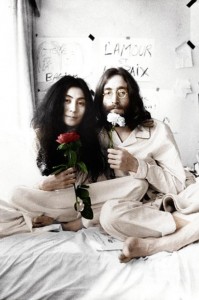

J.D. Salinger could have never predicted the way lunatics perceived his work with Catcher in the Rye. And, in an ironic twist of fate, the victim of one of those lunatics, John Lennon, could have never have imagined that someone would cling to a song from the White Album while preparing for a supposed race war. George Orwell likely didn’t expect governments to take his works as a field manual decades later. (Though one could argue the real problem is no one in the government has read Orwell’s books)

But, regardless of what their intention was, the debate will forever continue. Catcher in the Rye was at one point the most censored book in the United States. Helter Skelter is now forever linked to the heinous actions of Charles Manson. In fact, in Lennon’s time it wasn’t unheard of to have his music labeled the work of the devil.

|

| One can only guess the horrible things they did with those flowers |

But what exactly is the responsibility of the creator when it comes to their impact on society? For every generation there’s something that’s considered a corrupting force. As creative works explore the realms of sex, violence, drugs and the darker sides of human nature, does this somehow inspire problems in society itself? The people involved in these creations come to grapple with these questions and address them in their own ways. Recently, Jim Carrey, faced with the realities of recent school shootings, decided he could no longer condone the role he played in creating Kick Ass 2.

|

| Seen here, laughing about a man having a dog gnaw at his balls. |

“I did Kick-Ass a month before Sandy Hook and now in all good conscience I cannot support that level of violence. My apologies to others involved with the film. I am not ashamed of it but recent events have caused a change in my heart.”

Of course, it wasn’t so much that Carrey was saying that movies cause violence, rather that he didn’t want to be a part of such violence. It’s an understandable stance, but it does make you wonder if Carrey has come to the conclusion that such movies actually perpetuate the violence themselves. Mark Millar, the writer behind the Kick Ass comics (which were far more violent than the movies based on them) had a very different reaction to the same issue… in typical Millar fashion.

As you may know, Jim is a passionate advocate of gun-control and I respect both his politics and his opinion, but I’m baffled by this sudden announcement as nothing seen in this picture wasn’t in the screenplay eighteen months ago. Yes, the body-count is very high, but a movie called Kick-Ass 2 really has to do what it says on the tin. A sequel to the picture that gave us HIT-GIRL was always going to have some blood on the floor and this should have been no shock to a guy who enjoyed the first movie so much…

… Like Jim, I’m horrified by real-life violence (even though I’m Scottish), but Kick-Ass 2 isn’t a documentary. No actors were harmed in the making of this production! This is fiction and like Tarantino and Peckinpah, Scorcese and Eastwood, John Boorman, Oliver Stone and Chan-Wook Park, Kick-Ass avoids the usual bloodless body-count of most big summer pictures and focuses instead of the CONSEQUENCES of violence, whether it’s the ramifications for friends and family or, as we saw in the first movie, Kick-Ass spending six months in hospital after his first street altercation.

|

| Mark with a “water” bottle filled with either vodka or children’s tears |

In the end, it’s two very different perspectives on a situation that no one was very happy with. As creators we have a strange sense of pressure from the idea that our artistic visions may inspire or be corrupted by others. That our work may be co-opted by people who needed some excuse to carry out the actions swirling through their minds. But in the end, the answer behind it is that, no, it’s not our responsibility to predict what people will believe is out there. It’s not our responsibility to sanitize our work for a specific mindset and move in fear of society’s reaction to our work. I don’t say this with the belief that there is no impact of our work on society, all good art has some impact on society. But sex, drugs, violence and the darker natures of humanity in your work, in fictional work, are not meant to condone actions in society. Rather, as storytellers, our job is and will always be to make people think, imagine and feel. And what they feel? We can’t always control that.

So, as a final note on the subject, I leave it to a pair of individuals who spoke on this topic nearly 2 decades ago. Here, in a (unusually lengthy for me) video of a luncheon held at the National Press Club, Siskel and Ebert, two great analysts of art in their time, talk about these issues as they were seen from their day. And one of the most important statements on violence in art comes from Ebert himself as he says:

“To say that a movie or a song contains something is not to make a meaningful statement about it, except simply to say that is a factual statement, that this is what it contains… I think you have to look a little further into tone, mood, message, purpose, context and origin in order to understand whether a movie or song has a message that’s worthwhile or whether it’s simply negative and destructive. And that’s something I think Sen. Dole and other people who have joined his cause have not been willing to do.”

I think we can all apply it to our work.