For a long time I was uncomfortable with the idea of trying to teach anyone about the art of writing. Anyone who reads blogs about writing is often a writer themselves, after all. So what exactly could I teach someone who should have as much or more experience than me?

As a result, I spend most of my time on this blog trying to entice people into the world I’ve created by doing tongue-in-cheek in-universe articles about creatures that wander my world. But today I realized, since this is National Novel Writing Month, a lot of people right here and now are writing their very first novel. Not only that, but I’ve realized after some experience tutoring in screenwriting that not everyone who has had formal education in writing comes away with the same information. There are some things that people miss until experience and experimentation point it out to them. So, given that I’ve written two novels, there just might be something I can show a new writer that they haven’t thought of yet.

So, in the spirit of NaNoWriMo, I present writing tips today for one of the genres I’ve tackled: Mysteries.

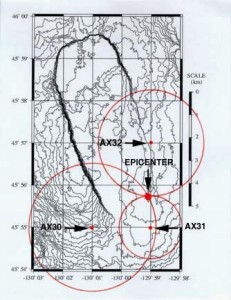

1. Triangulation

It may be strange to hear, but solving a mystery works a lot like finding the epicenter of an earthquake. To find the epicenter of any major event you always have to measure the unknown point against three known points. That sounds like it has almost nothing to do with mysteries, except for the fact that when you look into real world investigations you’ll notice that they do it too. Means, Motive and Opportunity have been something every basic crime novelist has known for decades and the reason why is because it works.

You see, one piece of evidence is coincidence, two pieces of evidence is suspicious, but three pieces of evidence pointing in the same direction is usually a sign. Now this doesn’t mean that everyone who’s ever had three pieces of evidence levied against them has absolutely done the crime. But when you look at most investigations and mystery stories, if there’s any less than three pieces of evidence at play then it’s usually not enough to make a credible case.

This also doesn’t mean that your detective has to avoid moving without those three pieces of evidence. If they find that one element that is out of place then they have more than enough reason to start looking into something. The idea is just that you need to make sure that when the story is wrapped up that they’ve found more than just one or two elements to point at the person who did it.

As a corollary to this, it’s not recommended to have someone caught in the act of committing a crime without having your detective do some ground work. While witnessing the crime itself means you don’t have to do the harder task of seeding clues in the story, if you don’t seed those clues then people will be unsatisfied with the end result. For example: if your story opens with your protagonist witnessing the crime, the mystery is going to be why the crime happened, not the crime itself. Your readers are going to expect this, even if they’re not sure why, and they will be disappointed if they don’t see it.

2. Don’t Show Your Hand Too Early

So one of the easiest rookie mistakes I’ve seen has been showing your hand in the first act. It’s a common problem for people not used to writing mysteries. You’re told often in writing classes that you shouldn’t hold anything back from the audience, so when you enter a genre that thrives on the idea of holding things back until just the right moment there’s people who have some difficulty with it. Writers, especially new ones, struggle with this a lot and sometimes their struggle leads them to doing things that don’t make a lot of sense.

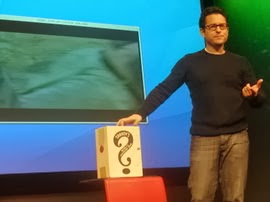

In fact, some people who struggle with this have gone to such extremes that they become ridiculed for how far they’ve taken it. M Night Shyamalan and JJ Abrams have made careers out of the idea that they’re going to hide something until the last possible moment and both of them have had some backlash from audiences when they take it too far.

|

| JJ Abrams even goes so far as to give it a name: “The Mystery Box” |

So here’s the thing, you need those three things to point at the suspect but you don’t want to reveal all your secrets too early. Trying to reveal those clues without revealing everything can be an incredibly tricky situation. But there’s three methods I’ve seen to work really well when done correctly and they’re something to keep in mind as you’re weaving your story.

The first method is to avoid showing those three pieces of evidence all in the first act. Simply pacing them out across the acts of your story will give you the appropriate time to make the mystery work and will naturally generate doubt as you find other people who may have one or two of the necessary traits to be a suspect.

The second method is to make your three pieces of evidence something that doesn’t mean anything until the bigger picture is observed. For instance, perhaps the killer is a nurse who visits the same coffee shop everyday and happened to know the victim (who died miles away from the shop). From a distance this looks perfectly innocent because people go to coffee shops. It’s only later when you find out the guy was poisoned by a slow acting drug dropped into his coffee that you realize the woman with ready access to drugs is someone worth looking at.

And, of course, the most famous of the methods for avoiding tipping the hand, and sometimes trickiest, is the…

3. Red Herring

Everyone knows about the red herring, it’s one of the most famous plot elements in the world right next to Chekov’s Gun. But a lot of new mystery writers don’t know quite how to use a red herring effectively. How do you make someone look like “the one” without them actually being “the one”? It’s also a problem because a lot of the bullshit “reader-writer contracts” floating about the internet today keep trying to tell you that you can never mislead your readers for any reason. That’s a problem because there’s a solid truth to being a mystery writer you must always remember:

Your first duty as a mystery writer is to mislead your audience as long as humanly possible.

One of the most effective ways to use this is by using the triangulation method from earlier. Note earlier I used the term “at least three” more than once. This is because Red Herrings are the characters and clues in your story that have three elements pointing at them to make them perfectly logical answers while your actual suspect could have three other elements that work better.

You can show your suspects side by side with their three elements for the entire length of the story so long as you make them equally viable. But later you can then prove or disprove those sets of evidence with a fourth piece of evidence. It’s when the fourth piece of evidence tips the balance that one of the suspects becomes “the one”.

So long as you eventually come clean on who did what and make sure that your criminal at the end still makes sense, you’ll be fine. Everyone is going to look, even if just subconsciously, for three pieces of evidence that will clue them into who did the deed. If that instinct just so happens to point them at an innocent person… well then you couldn’t possibly be blamed for that, could you?

4. The Mystery Isn’t For You

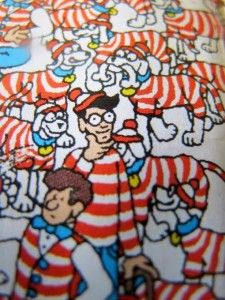

|

| You know who never looks for Waldo? Waldo. |

Now once you’ve left all of your breadcrumbs, one of the other most common issues I’ve seen with mystery writers is that sensation that the whole thing is too obvious. Trust me, I’ve felt it myself so it’s perfectly normal. At first I thought it was a logical feeling because the idea because the bread crumbs you’ve left for people to figure things out seem to be so damn obvious that you can’t imagine them not seeing it.

However, this is usually a matter of perspective. Of course they seem obvious to you, you’re the one who put them there. Throughout the time that you’re writing this mystery you’ll never come to the point where you don’t know the outcome because you’re the one writing it. There is no mystery for you, there never will be, and because of that you can’t accurately tell on your own if something is too obvious or not obvious enough.

This is a huge problem for some writers, the other side of the coin for “showing your hand” from earlier. In the fear they may be too obvious, some writers will go overboard and start trying to cover everything in a heavy layer of misdirection that leaves the reader so confused by the end they don’t know what they actually read. Sometimes this can be recovered from by spinning off into a deeper mystery. But more often than not you’ll find that you’ve left a convoluted mess because of a moment of insecurity. So before you give into that feeling that you’ve made it too obvious, get a trustworthy third party to read the first draft.

5. Don’t Worry About When People Catch On

|

| Hiding well, still visible |

And that’s when you’re going to know your results, when you’ve gotten people to take a look at it and have gotten their feedback. This can be nerve wracking but also a bit liberating. When I completed my first book I had six people read either the complete draft or excerpts to get an idea of how well I did and what I might need to hammer out. What I found after the fact was amazing and relieving. After all the insecurity about whether the bread crumbs were too obvious or if I put in enough pieces of evidence I found most of it really didn’t matter. So long as I covered my bases and had the necessary elements in play it was going to work regardless because everyone is going to react to the clues you left differently.

Of the five who read the complete draft, while most of them caught on at different times throughout the story, one figured it out in the first act while another was left so stumped that she scolded me in her feedback for not providing “clues”. I knew if she was right none of the other four readers would have been able to figure it out either. But since all of the other four were able to see the clues I had left at different points in the story I knew it wasn’t my story that was at fault for what happened. And, most importantly, their ability to catch on had nothing to do with their status or education: the person who couldn’t figure out what I had done was the most educated reader in the entire group.

Better than that, the people who caught on didn’t have the mystery ruined for them. In fact, when they figured it out it became less about anticipating the answer and more about anticipating the reveal to prove their theory. If you do it right, a reader who catches on will feel invested in having their theory tested against the actual results. Because, when all is said and done, the biggest motivator in just about any part of modern entertainment… is ego.

Blood on the rail, scream from the next room, closed glass door: Three things!

And on a final note: Good luck on NaNoWriMo and don’t feel bad if you don’t finish in one month. I started both of my novels on NaNo and didn’t finish them for months after I started.