As I said yesterday, violence in our media is necessary in our culture for an open discussion. We should try to avoid censorship whenever possible because that only tends to make it worse. But then we have the fact that not everyone does violence well. In fact, one of the hardest things to do is to create an action scene in writing without losing the reader or making it seem silly. So for today’s “Tuesday Tips” (yeah, I’m dedicated to this bit) I’m going to be talking about things to keep in mind when writing action scenes.

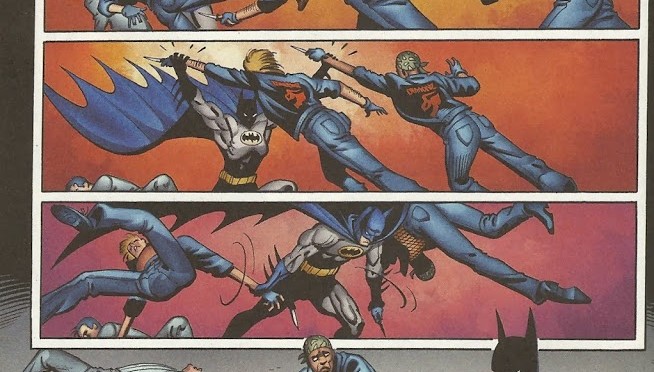

1. Adjust the pace to the medium

One of the major mistakes of a lot of new writers is not realizing that every medium has completely different pacing rules. Film flows almost completely different from prose and both flow entirely different from graphic novels. But a lot of writers have to learn this the hard way and it is no truer than on the topic of action scenes. Many writers, especially today, are inspired to get into writing by film and television and have the pace of those mediums in their head as they approach stories. This can be a huge mistake.

In film, your genre determines a lot of how, when, and why you can include an action scene. In fact, in the more action oriented genres it is normal to include an action beat once every 10 pages. So there will be quite a few action scenes over the course of a single script in that genre. On the other hand, you don’t want to go writing too many knock down, drag out fights in a romance movie and if anyone is going to throw a punch you may want to hold it for the third act.

Prose, on the other hand, tends to follow the rule that action scenes happen when the story lets them. There’s no requirement for pacing according to specific lengths of time but rather for the build. People who are reading a book are naturally being more patient with you and are more interested in the words on the page than some may be with the words on the screen. So you can hold back on the action, even in an adventurous book, until it makes sense.

In essence, while pace can be determined in film by action, in prose, action must always naturally follow your established pace. Do not try to approach prose with the idea that there has to be an action scene once every so many chapters – your story may end up looking stupid.

|

| Picture a novelization true to Bay’s vision and Shia’s acting |

2. Dynamic Words for Dynamic Moments

When you’re writing prose (and scripts, for that matter), one of the key things about making people want to keep reading it is to make sure your language shifts enough that the reader starts to see more energy in it. You don’t really think of it much in your day to day conversation, but the more mundane and common a word is, usually the less energy it feels to have. Consider how often you see people walk, run or jog compared to dash, dart or scramble.

It seems like a silly thing to do, but when you read words like “scramble” you picture more than just the motion, you picture the emotion behind that motion. Why are they scrambling? Are they panicked? Clearly the sound of it suggests someone under pressure, scurrying for cover or just simply out of the line of sight of something trying to get to them. And when you can have the motion invoke the concept of an emotion, people will start to get into it more.

But the thing is, you can’t use these words constantly. If you do, they will only cause harm to your story. For instance, if you were to use these words during the more common, mundane sequences, when it becomes time to make an action sequence you’ll have no deeper to go to give the reader that feel like something more dynamic is happening. On the other hand, sometimes worse, you can make the normal parts of the story feel silly because the characters seem to be having such a dramatic reaction to simple things.

|

| Either one is a bad sign. |

3. Make sure people care

One piece of advice I was given myself in the past is that you should never have a gunfight unless the audience cares if someone there is going to die. The purpose of this was to say that you shouldn’t really include gunplay until a couple of acts are under your belt to justify people caring if one of the characters happens to get grazed. But is it that simple?

I think in some stories the idea of frequent gunplay is going to come up and the threat of death could and should loom over the heads of the characters involved. But in that case, how do you make sure the characters are worth caring about? The thing that came to me eventually was that action scenes should have a purpose, a meaning and something that will motivate the readers even if they’re not familiar with the characters yet.

One example would be if you were writing a story about soldiers carrying out a specific mission. While the first act wouldn’t give you nearly enough time to make people care about the individual soldiers, you can make people care about why the fight is taking place. Maybe they’re rescuing someone, defending the helpless or being ordered to do something they don’t agree with. In the nature of the mission you’re given an opportunity to say something about the characters in the very act of defining why they fight. You don’t want to have one of them wounded in the early stages of the story (unless that IS your story), but you can still have meaning.

4. Know your audience/message

And when you do make that situation happen and you’re telling that story, it’s important to remember your audience and the message you’re trying to convey. A lot of times writers will go for excessive blood and gore when it’s not appropriate and turn off the audience in a way that makes the action scene a detriment to the rest of the story. But of course, there’s always a time when the graphic descriptions can be used effectively.

One proper use of graphic descriptions would be if you’re looking to shock or horrify your audience. You don’t want to describe it just as a run of the mill scenario, rather as something where you’re actively trying to disturb the reader. This may turn some people off, but if done correctly, another branch of the audience will actually be a little excited about it. These people are sick puppies, but they’re also the kind of sick puppies that will be loyal to your work over the years. So reward them a little for being so twisted.

On the other hand, maybe you’re trying to convey a message with it. Maybe you want to write about the horrors of war and make people realize just how horrible it actually is. If that’s the case then you can use the graphic, visceral nature of your scene to make people feel that sick pit in their stomach that tells them what they just read is wrong.

And that’s the key thing about graphic violence, you’re communicating to the part of the human consciousness that knows what they’re reading is wrong. You have to remember that as you approach it and treat it with that kind of respect. Yes, some will be enticed by the wrongness of it, but even they will recognize that it’s still wrong. So don’t use it at every turn, don’t trivialize it, because your audience won’t do the same.

5. Follow Through

One of the things that also needs to be understood is that every fight scene is essentially a more active version of a Chekov’s gun. Every time an action scene takes place, there will be a consequence or follow up. Sometimes this is brief, but it still must exist. If you were to write just a fight scene that had no purpose or point, and if it never paid off later on, people are going to wonder just why exactly it happened at all. For instance, while there’s very little reason to have your character in a street fight if he happens to be a detective, it is actually a pretty good device to show how he thinks.

But then you can’t just leave it there. If he’s just having a fight for the sake of showing how he thinks, you could have done that in a better fashion. So to resolve it, you need to tie it back into later parts of the story. For instance, if he later has to defend himself against a stronger opponent during the course of his investigation, the original scene pays off because then it had a purpose that extended beyond itself.

When you don’t follow through and have some connection to the rest of the story (a rare thing), you can find audiences reject it. A recent new anime, Space Dandy, had the first episode of the series end with the entire main cast caught in a planet destroying explosion. In the next episode, everyone wondered how they could possibly continue the series on after something like that. When it turned out that the second episode began with no explanation for what had happened, there was a large contingent of the audience that was confused, disappointed or angry.

|

| And the show isn’t even trying to be taken seriously |

Now, if there is eventually an explanation for how they survived that explosion, all will eventually be well. But if it is left that way for the rest of the series, it may very well be the thing that ruins the entire series for those people. That’s the kind of reaction you can get for not following through. You can’t have an action sequence begin and then drop off without resolution, you can’t have it happen without it tying into the rest of the story and you can’t just write in a fight just for the sake of a fight. Even a movie about a fight has to show how that fight ends and what people’s reactions are to it. Think about it, what’s the most memorable line from the Rocky franchise?

Exactly.

(Today is my 100th post to this blog. If you like the blog, or if you just like me, please remember to share with your friends, family or random strangers on the street. And, as always, remember to buy my books which are witty and full of dynamic stuff.)