Slavic Mythology

Now a lot of you would start to wonder why it is that, of all the dragons, the only one to stand on its hind legs would be the Slavic one. The answer is pretty simple. A while ago I mentioned that dragons, like most monsters, were the embodiment of the fears the people had. The idea that your village could be burned down by something from on high was a credible fear to have. But this is no better exemplified than by the Slavic version where the Slavic people, despite not speaking it, chose to use the Turkish languages to give their dragons personal names.

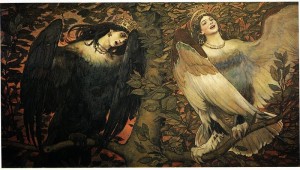

Slavic Sirens (Sirin, Alkonost, Gamayun)

Sirin

The Sirin is, for the most part, like the original Siren. It would sing to people and make them forget all of their worldly desires and convince them to throw it all away in order to reach the beautiful singing of the bird-woman in the distance. This usually led them to their deaths like in the traditional Siren song stories.

However, a slight twist came of the Sirin’s connection to Saints. In the Slavic mythology, a Sirin’s song was only dangerous to the impure, mortal men who would hear it. The Saints, being the most pure of souls, would hear only songs of a joyful future lying ahead of them. In this way, the Sirins were almost like the Muses or Oracles of the Hellenistic mythologies because they could inspire the Saints rather than condemn them while giving them information of a divine nature.

But these two contradictory traits of the Sirin eventually evolved into two completely separate entities.

Alkonost

The Alkonost, one of these two offshoots of the Sirin, was the one that inherited the beautiful Siren song ability. In most cultures this would have essentially made them a word for word translation of the traditional Siren. But for the Slavic people this is an opportunity to put their own twist, one which brings some interesting cultural cues to light.

You see, rather than being drawn to the bird and their death, the Alkonost’s song simply inspired a complete sense of joy and satisfaction, one so complete that the person never again wanted anything in their lives. In fact, once the Alkonost became a fixture in the culture of the Slavic people, it was often depicted as a parallel to the Sirin, the two of them representing good and bad outcomes. However, which of these is which is somewhat up for debate.

From our western perspective, it would be easy to argue that the Alkonost is just as bad if not worse than the Sirin. At least the Sirin, despite leading most people to their death, would be able to sing to the Saints and inspire them for the future. But the Alkonost’s ability of removing all wants from their lives would, in theory, strip that person of all ambition. Combined with the fact the Alkonost lived in the underworld, it would be easy to argue that was the “bad” bird.

But that would be forgetting that the Slavic states eventually became the Bastion of communist ideology for years. Food for thought.

Gamayun

The other aspect of the Sirin, the one of divine inspiration, evolved into an entity which possessed the ability of prophecy. The Gamayun wasn’t deadly to anyone and it wasn’t going to grant the listener eternal joy. But what it did grant them was a view of the future. This makes it somewhat less interesting in terms of story telling, more akin to a fortune teller in bird form. But the evolution of what was traditionally a deadly temptress into a benign soothsayer is something that can only happen in a country that’s seen it all.

The Vedi

The Vedi were an interesting combination as well, featuring traits similar to giants, house spirits, Woodwoses and even parallels to Sasquatch and Yeti from far away lands. They were a more regional myth than most, occurring only in a small corner of Croatia at the far end of the Slavic territories. But in those regions they were incredibly important to the people.

The Vedi were giants, the size of a house and covered in fur. They featured chests so broad that they could blow storms or be heard singing for miles around. They were incredibly strong, able to uproot a tree or cause damage to a house. And these giant Vedi were attached to specific regions, dividing up into two different kinds. The forest Vedi, unassociated with humanity, were neutral to humanity as a whole but would take people as their slaves if encountered. While the good Vedi, friendly to the human race, were so attached to people that they would respond to the requests.

These friendly Vedi each protected a household, acting in their interests when they called to it for help and protecting them from natural disasters and from others who may wish to harm them. The Vedi were even said to be potentially summoned by the family of a particular household to go on the offensive against others.

The Vedi once again embody some of the key changes of the Slavic people vs. the rest of Europe. While the concept of a household bound spirit is quite common throughout Europe, they were typically smaller creatures such as Brownies who would work in secret and hide. This made sense, what with not being able to actually see them. But the Slavic culture, being under constant threat from outside forces, required a more sturdy entity to help them through their days. As a result, while they were said to be giant, the Vedi were also said to be able to turn invisible and only be seen by certain gifted individuals, the number of these people who could see them slowly dwindling over time until they ceased being mentioned in the 19th century.

They may very well still be out there, invisible to a world of unbelievers. Which would be one of the reasonable explanations for why I can’t find a single picture of one.

Koschei

The Slavic mythology is made of a lot of good ideas altered into new, twisted versions. In fact, almost the entire Norse pantheon and cosmology has also been adapted through figures such as Perun and the Slavic version of the world tree myth. But a few concepts are uniquely Slavic in origin and exemplify the beauty of a group of people that have been under the threat of violent death for as long as they’ve existed. I present to you, Koschei the Undying, a Wizard who literally refuses to die and will do whatever he can in order to accomplish that.

Koschei is the epitome of the Slavic mentality. Afraid of the concept of death, Koschei found that the easiest way avoid it would be to remove his soul from his body (once again, refer above) and place it into a needle. He then took that needle with his soul in it and placed it inside an egg, which he then placed inside a duck, which he then placed inside a hare like some sort of struggling Russian nesting doll. However, unsatisfied with this placement of random objects up the ass of a rabbit, Koschei then put all of that inside an iron chest which he hid on an island. The island, Buyan, would then disappear, taking with it what I will now call Koschei’s “Turfuckit”.

In theory, the soul was perfectly safe from there on. If one were to open the chest, the hare would run away. If the hare were killed, the duck would fly. Only after getting the egg would one have complete control over Koschei, cutting him off from his magical power and acting much like a voodoo doll on his mortal frame. But, even then, he would not die until the needle and egg were destroyed, according to some stories this even required being cracked across his forehead.

To put it bluntly, someone would have to be incredibly determined to kill this fucker.

But Koschei still wasn’t satisfied with this. You see, in the Slavic traditions, Death is embodied by a goddess. Koschei, being an evil wizard, also had a tradition of kidnapping women and decided that the goddess of Death looked pretty kidnappable. So of course, that’s what he did. After all, if his soul were safely away up a rabbit’s ass, the only person left to really kill him off would be Death herself. So Death became his unwilling house guest.

So, of course, most of the stories of Koschei to have been written throughout time are people trying to kill the evil son of a bitch. Still, you have to give it to him, he finally answered an age old question…

Koschei, Koschei wants to live forever.