Recently I raised the idea of the Fermi Paradox and the possibility that the “Great Filter” might be behind us. In my view, that raises a lot of interesting questions that scifi writers could get a lot of mileage out of. The idea that life is so hard that it needs to have a great deal of luck to get to even our level is something that would greatly change the typical dynamic of most scifi stories to date. We could be a relatively rare form of life, maybe even among the first, that has achieved our level of intelligence.

But that does require that our specific circumstances are unique, which brings us back to the original premise. With a universe so complex and so ancient, you would have to imagine that our pattern of events isn’t completely out of the ordinary. It is entirely likely that most worlds in our universe have experienced at least one major extinction event once life has formed. And, while the easy assumption is that the Great Filter is when one of those extinction events can’t be recovered from (like what may have happened to ancient Mars or the like), we have to assume that surviving those events can’t be too unique either.

So… what kind of situation do we have if the Filter doesn’t exist?

Life Unfiltered

The kinds of possibilities that open up when you stop fearing the idea of a Filter are just as strange as the possibilities that open when you consider it behind us. After all, despite my rather positive outlook on the existence of aliens, you have to admit that the lack of contact raises some questions. If there is no Filter, and thus life becomes intelligent like us on a semi-regular basis, one would have to then concede that they should have left their planet after a sufficient amount of time. So that brings us back to the original paradox and its question: where are they?

Silly as it seems, the answer is obvious: where we haven’t looked yet. It’s easy to forget that, even if you can look up and see the whole sky rather easily, the actual process of searching for exoplanets and listening for signals is actually relatively narrow and slow. The SETI institute, despite dedicating all of their attention to this task, has still only covered an incredibly small fraction of our own galaxy. To put it another way, there are billions of stars out there and we have to actually point our equipment at one to listen to it – so how do we know we’re pointed the right direction at the right time?

But that’s generally not what the paradox is addressing when people bring it up. Because, despite the fact we all know on some level that the universe is big, what we’re really asking is why they don’t happen to be sitting next door. Well, a quick look at what we have found so far suggests something we have to consider…

Common Life, Rare Planets

One of the things we have to realize when we consider the Fermi Paradox is that we’re expecting these alien civilizations to do something we’re not entirely likely to do ourselves. As we look out at the cosmos we find a great number of exo-planets that we wouldn’t exactly consider pleasant for us to stand on: red-hot chunks of rock, super-jovian gas giants, tidally locked super-earths. The premise that an alien race should have populated the entire galaxy by now would first require you’d actually want to. Gravity on its own makes for some unpleasant effects when it’s wrong – too little and your skeleton degrades, too much and…

So when we look out at the rest of the galaxy we have to stop considering every rock we see out there to be prime real estate. Even within our own neighborhood we never got around to that Lunar colony business because we saw no point and, honestly, who wants to live on a lifeless rock? The most Earth-like planets in our neighborhood are Mars (too small and too cold) and Venus…

Estimates show it would take us a couple hundred to a couple thousand years to terraform the likes of Mars with methods we’re aware of. So put yourself in the shoes of a distant neighbor looking for a new place to go. You’re going to want a planet that is the right size, temperature, and with an atmosphere you can work with – otherwise there’s not a whole lot of point to it. Terraforming could work, but that takes generations.

At this point it comes to a simple but profound realization – while life itself may be relatively common, uninhabited rocks which happen to match our perimeters are likely scarce. If a star system happens to only have an asteroid belt, it wouldn’t make a lot of sense for an alien civilization to take a one way trip to colonize a rock they likely couldn’t live on without some major construction. And as for the places they could probably live comfortably on? Probably taken.

Sure, this means the alien invasion trope could be happening a lot, but consider how hard it would be to wipe out an entire civilization of our size without ruining the planet at the same time. It could take a while, progress could be slow and likely not worth the time. Sure, we could bombard a planet with asteroids or drop powerful weaponry on it, but then we might as well just have built that colony on the lifeless rock instead.

So finding a planet you want to live on that isn’t going to be a pain in the ass to colonize, and won’t aggressively fend you off? That isn’t likely to be easy. This is especially important to figure when you consider that we live in…

A Relatively Rough Neighborhood

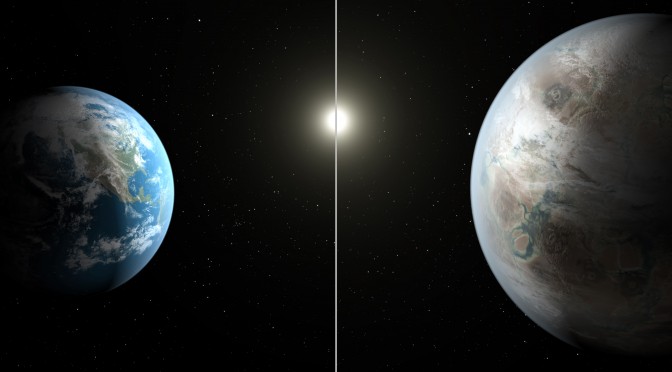

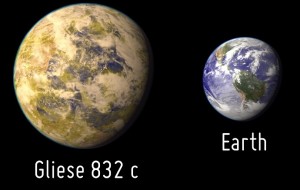

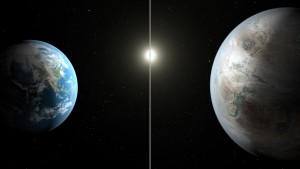

Exo-planets are apparently really common, and there are a lot of really interesting ones we’ve discovered so far. But you know what we haven’t quite discovered yet? Anything remotely looking like Earth.

A lot of people get confused about that because of the term that gets thrown around known as “Super-Earth”. We usually see articles that proclaim how we’ve discovered a sister planet or an “Earth 2.0”. But what most of these tend to leave out is the fact that these planets, while being compared to Earth, are still (so far) nothing like us. The average Super Earth is anywhere from 5 to 10 times the mass of Earth, with a gravity to match. Typically we get happy when we find one that is only twice the size of Earth. And usually when we do find those smaller planets they’re too far or too close to stars that aren’t the right temperature. To find one exactly like ours is almost impossible in the narrow range we’ve searched.

Frankly, if we had to compare our corner of the galaxy to a neighborhood everyone could recognize, we’re living in Detroit.

Now sure, plenty of nice people live in our “Detroit” (at least 7 billion right now), but it’s not exactly the easiest thing to do. There are definitely worse neighborhoods out there (center of the galaxy might as well be Juarez), but it’s not exactly prime real estate so far. And the closest matches to Earth, the ones that get touted as “Earth 2.0” by the media?

Five times as heavy and over a thousand light-years away. So the planets we’d be looking for (and likely “they” would be looking for) aren’t necessarily “next door”. And the closest we can find are the “older, larger cousins” of our world – rocky, but not necessarily one we could walk around on unsupported (unless we wanna be Yamcha).

But, let’s say, just for a moment, that this other planet which is an “older, larger cousin” to our planet did happen to have life on it. We often assume that means we should be able to hear something off of it. However, if they’ve had a billion years head start on us (and that’s being generous, if you remember the last post), there’s a damn good chance…

We’re Using The Wrong Tech

Right now, SETI’s process of looking for life is limited to finding civilizations like ours – tracing chemical markers and communication methods familiar to us. One issues with this is that natural chemical markers of life exist even in places that don’t have it (such as methane) while artificial markers are specifically generated by our technology. Right now we’re using fossil fuels, using several industrial processes, and have polluted a great deal of our environment. It’s fair to assume that some civilizations may have done this over time, but let’s be honest – we can’t keep it up for much longer ourselves.

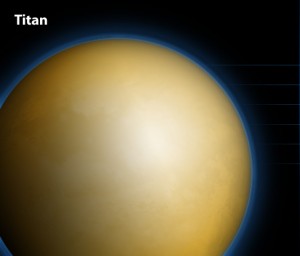

So the idea that all alien civilizations would leave the exact same chemical markers is a little unreasonable. There may be a few that can be assumed, but not all. And anything more developed than us will definitely avoid the greenhouse gases we’ve spewed into our own atmosphere (hopefully before it kills them). So the chemical traces are going to be limited to natural ones at most and, even within our own solar system, we’ve found a few of those are more common than we’d think.

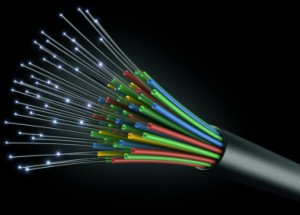

As for the signals, terrestrial communications even on our own planet long ago started to transfer to something more stable, clear, and powerful with the use of technologies like fiber-optics. Through fiber-optic cables we use pulses of light to transfer information from point A to point B without the random refraction that would normally happen in radio communications. Though we can’t use it for everything (yet), what we do use it for isn’t going to generate a signal that could be detected light-years away.

In fact, point to point communication in general is going to be hard for us to detect if it’s focused in any fashion (which most really long range signals would). Why? Because we’re not their target and if they’re going to reach their target they’re going to want to make sure it’s as focused as possible. Any lack of focus could result in signal degradation and that would be really messy across incredibly long distances. A sufficiently powerful radio signal could reach interstellar space and still retain some information – but it would have to be shot out there with the intent of communication with “whoever”. Otherwise, it’s going to sound like noise.

Meanwhile, the real whopper is if (and this is a big if) a civilization figured out FTL it would be difficult to communicate long range without finding a similarly impressively fast method. How they would communicate over vast distances is far beyond what we could detect because if we had any clue how it was done we’d be doing it ourselves. Or, to put it another way: if they’re talking like this…

We probably wouldn’t overhear it.

(I write novels. Follow me on my twitter account for other stray thoughts and views into my work. In the meantime, if you’re seeing this, Xenu, take Scientology back!)