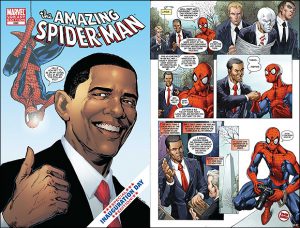

Any long time reader of comics knows that any major event that happens in the world is inevitably going to be reflected in comic books. Marvel and DC’s golden age of comics were based primarily in the war-time propaganda surrounding WW2. The civil rights movement in the 60s got a lot of references thrown into the X-Men comic books and other silver age works, to great effect. A memorial comic of sorts was published in response to 9/11 (to slightly lesser effect). And Obama becoming the first black president even got a shout out in Spider-man,

Given that, you’d expect recent world events to fall into these things and, generally, they do. The rise of terrorism has been addressed repeatedly in different titles, especially as the Iraq and Afghanistan wars were at their peak. Even the movies based on them have had clear undertones of certain events, even if the countries they represent are fictional and distinctly not Middle Eastern. And, a few years ago, Frank Miller tried to pitch a Batman comic where he’d go to fight Al-Qaeda. DC thankfully pulled that one (but couldn’t stop him from self publishing as an original IP). But as of right now there’s one political element in the US that’s running strong which, given past events, I imagine someone in the comic book industry is chomping at the bit to get to.

And, I’m going to be honest, I really hope they just leave it alone. Because, for all the great stories you can probably think of, the truth is that comics really suck at politics.

High Contrast, Low Resolution

Leading up to elections, comics typically stand back from the issues unless a groundswell of support rises for a person or an idea, something that tells them they’re safe to move forward. But following the results, we’re likely to see some reference, somewhere, about how it turned out. If Hillary Clinton were to win, like with Obama, it would be a historic moment that your standard publisher would want to capitalize on for all its worth. And if Trump won, well…

So, while it’s impossible to know for sure just how far they would go, I do have a fairly good hunch that it wouldn’t go over well. A name drop, a cover image, maybe even a cameo at some point wouldn’t be out of the question. Maybe the President in-universe looks a bit like the sitting President for the next few years. But the thought of these things being referenced recently made me realize just how incredibly bad comic books are at politics in general.

Some would look at the history of comics and say that they’re generally better when they reflect the real world. As I said before, the X-Men were couched in the very concepts of civil rights and continued to reflect that for all the challenges facing our country. In the course of their decades long run they’ve dealt with hate groups, racism, bigotry against the LGBT community, and the history of governments siding with bigots. It’s provided a rich history of stories that have reached people of all walks of life and shown them something that they might not have seen before. But what many people fail to recognize is that generally those are not about politics but instead about ideologies.

There’s a difference, generally overlooked in today’s society, between your political alignments and your ideological ones. It’s easy to understand why, after all, because your ideological stances influence your political ones. But when you really sit and think about it, the differences can be subtle yet profound. An ideology, while forming the bases of how you think, is also generally full of broad strokes and idealistic views of the world. The world, seen through ideologies, generally has very few shades of grey and very few precise details. Politics, meanwhile, is all about the nuts and bolts and sometimes those aren’t things you can agree with ideologically.

This is particularly clear in today’s climate where your average primary can become incredibly contentious. For all the things they agreed about ideologically, the politics of the moment resulted in an incredibly caustic environment. At one point 17 people ran on one side and managed to both agree and disagree within the same breath. This is because, while they all agreed on the very basic ideology, the details of how you achieve the ideal were seen as very different between each person. This is the very nature of politics, agreeing on a goal and disagreeing vehemently on how you get there. And in the end, the guy that won the ticket on that side was the one who had almost no details at all.

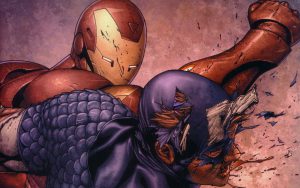

And that’s why I sit here now and tell you that comic books, generally, are pretty damn bad at “politics”. A great example of this sort of difference sits with the idea of “registrations” in comic books. The X-Men, using broad strokes and talking more about the ideological and moral problems with such registrations, created some of their best stories in discussing the evils of a registration for people. But, despite this, when Marvel later approached the concept again with Civil War years later – it was actually pretty divisive among critics and readers.

The reason for this division is because of the dramatically different approaches to it all. The X-Men stories were often more ideological and talked about universal truths such as freedom, respect for human life, and an aversion to abuse of power. Civil War, meanwhile, was presented more as political debates would be – two sides trying to achieve the same basic goal but having incredibly different views on how you would get there. Captain America and Iron Man were both looking for the same end result, a safer world, but each had a very different idea of how that would happen. And, while the movie did fantastic, the comics were considered a mix bag and had significantly more flaws that were discussed for years to come.

Some would think this was because of the grey area involved in it all. The idea that the two sides being equally right could be perceived as too muddled for your average geek, but this is far from true. We’ve seen more than once that geek culture is capable of understanding complicated issues and often rally around these being displayed. Even in my childhood, both Star Trek: Deep Space Nine and Babylon 5 spent an astounding amount of time on political issues that were a little too complicated for me until adulthood. And today, I look back on Deep Space Nine in particular to say that, while not my favorite, it was probably the best written series of the franchise.

So the problem isn’t the subject matter, the Civil War movie managed to remain a complex issue where neither side was particularly wrong and it did fantastic. The problem is rather that the very format of comic books does not lend itself to politics as well as it lends itself to ideology. For whatever talent your writer may have, the act of putting politics into comics is very difficult, especially in certain genres. And that reason is because comic books, more than any other format, are driven by visuals and paced by the reader.

It’s something a lot of writers don’t consider until they actually give it a whirl. While a television series or movie are very visual things, the pacing is still controlled by the cast and crew and how they deliver the material at hand. You write something down, keep it within a general size range, and the people on set will make it happen in a controlled setting. Books, meanwhile, are more susceptible to the reader’s pace, but are still basically controlled since each word only takes up so much space on a page. But a comic book is almost entirely subjective. A reader could spend minutes staring at a single panel with no words but only seconds going through the next.

There are techniques to control this pacing, but what ends up happening is that comic books are largely controlled by striking visuals. And, while ideologies are easily conveyed visually, politics are often too difficult to tell in a single picture without coming away with caricatures. The very nature of the format means that the sides need to be more polarized to come away properly and that often leads to the narrative becoming lopsided. Essentially, no political cartoon is subtle and neither are political comics.

And this translates into very uneven storytelling. The need to make these contrasts stark so that the format can tell a gripping story means one side has to look “evil”. You need someone to look like the “bad guy” so that people get the right emotional impact from full page splashes of these characters. You need the storytelling to be simple enough to be translated to someone in a single image. And while they say that an image is worth a thousand words, the words in question are rarely nuanced. This often results in characters being almost irrevocably damaged by a story that should have made them look sympathetic. Years after the original Civil War hit the shelves, fans in certain corners of the community still haven’t forgiven Tony Stark for his part in the event. And, frankly, the version in the comics deserves the heat (and this, by the way, is from a lifetime Iron Man fan).

Ideological stories, meanwhile, can let you make the antagonist truly a bad guy without losing anything. The leader of a hate group is going to remain the leader of a hate group no matter what you do with them. You can try to make them sympathetic, but that doesn’t really damage the character, it just adds a layer. They’re still an asshole, you just feel sorry for the asshole. On the other hand, to make a good guy’s point contrast with another good guy’s point, one of them is inevitably going to cross a moral event horizon. The only way to prevent that from happening is to ensure nothing happens at all. This basically leaves the story bland, boring even, and full of dialogue that generally goes nowhere important.

To summarize, imagine you had a world that is full of colorful characters who strike iconic images. They live in a world that has very clearly defined ideas of good and evil, and they have battles between those two sides which are sometimes even color coded. Their major conflicts are generally black and white, their solutions absolute, and their sides divided by a very clean line in the sand. Now, I want you to take that world and picture it as told by C-Span…

And remember this example actually moved.

(I write novels and tweet. Recently, I even wrote a semi-successful blog post. I assure you, it was an accident.)