There are times when trying to articulate what I’m saying can be a little harder than others. I know what I want to convey but that’s sometimes more grey than people would like. It’s so easy, especially in the modern era, to be labeled as the enemy by everyone because your nuanced position happens to be neither firmly in the black or the white. Too often, the two sides are unable to see that there are a lot more people who stand somewhere in the middle. And, a little over a year ago, I walked right into one of those conversations accidentally while in search of something to post to my blog. Before I knew it, I was receiving a swath of comments and messages regarding copyright and the legality of fan-works.

As a result of the conversation, I’ve spent the last year writing a series of posts responding to a litany of polarized views. But in responding to so many varied opinions not everyone actually understood what points I was making at the time I was making them. From addressing the moral superiority some people thought they had, to pointing out that fair use isn’t quite as sturdy as people on the internet hope it to be – I’ve been trying my best to respond to everything while keeping my own position as clear as I could. And, frankly, despite my best efforts I know that something this complicated is almost impossible to keep clear in short order. In fact, I’d even go so far as to argue that’s by design.

But, not too long ago, someone on Twitter sent me one final question that finally crystallized the reason I got into the conversation in the first place…

Individual and Cultural Rights

It was during the big debate about whether or not CBS should have sued Axanar productions that I stepped into what turned out to be a bear trap. I hadn’t realized just how polarized the community had become over it (and I fully admit that was my mistake). From where I sat, the whole debate was somewhat more grey than the two sides were portraying it to be. On the one hand, CBS Paramount were absolutely in their legal rights to defend their copyright in any fashion that they saw fit. On the other hand, it had been a very controversial move to sue a fan production and the ramifications of that lawsuit could have rippled across an entire community of passionate fans. In fact, part of their reaction to Axanar was to establish guidelines that felt punitive to me because of clauses that indicated that you couldn’t get a cameo, couldn’t recreate scenes from the original show, and even had to restrict the length of time that any fan-film ran for. And, the thing is, at the time I wrote my piece on it, I was entering it with the opinion that CBS – while well within their rights – was being extra aggressive in their defense because they had seen Axanar as a commercial grade (and thus competitive) product.

Now this isn’t something unique to CBS, many companies are willing to allow a degree of freedom to their fans until they enter that competitive range, but CBS is one of the few to actually sue over it. Recently Nintendo had a similar situation to resolve – a high quality fan remake of Metroid 2 had been released under the name “AM2R” by a man who had made no profit from the production but had created something of a truly professional quality. Nintendo immediately contacted the man after he released it, DMCA’d the downloads they could find of it, and essentially shut it down. Now, they didn’t actually sue, and the situations weren’t completely the same because AM2R had never received any crowdfunding, but it still raised questions. And Reggie Fils-Aimé, the President of Nintendo of America, gave a clear, concise, and fair answer in my opinion:

“That’s where the line is very clear for us. And again, we could go on to YouTube and a variety of different places and see fans doing interesting things with our IP. But when it turns to driving the direction of the IP, or somehow monetizing or becoming a commercial project, that’s where for us, the line has been crossed.”

And that is where I felt CBS was coming from when they had sued. It wasn’t strictly about the crowdfunding, they could have quashed that before it got rolling since it was a very public show, it was the fact that this production had crossed well within the competitive realm. People took issue to the idea of my calling it a “threat”, but I still think that’s exactly what it was – a threat to their idea of where the IP should go. In fact, I think it was even a bit more of a threat because they weren’t quite sure what that direction was going to be at the time and couldn’t afford to let the fans go rogue at that moment. A year ago, climbing down into that hole, I could only make a guess at that, but in the time since then they’ve fumbled the 50th anniversary, lost Discovery’s first show runner, and encountered a great many production troubles and delays.

Thankfully, the situation ended with the best possible results in a case like this. The lawsuit was settled without setting any damaging precedents. Axanar still gets to be made in a limited fashion under the guidelines (which will, hopefully, be eased up someday). Discovery finally hit the air with its own unique take on the franchise. And I felt comfortable putting the subject to rest by making one last comment on how a DMCA or Cease & Desist (especially if done earlier) might have saved everyone a lot of grief. But then someone asked me a question that got me thinking again: “Would you let someone make a fan-work of what you do?”

Initially I gave the usual off-the-cuff answer that I always do: “If it ever happened, it’d mean I made it.” But, not wanting to take it lightly, I pointed out that there would be lines that shouldn’t be crossed. Like Reggie’s quote above, I wouldn’t want to lose control of my IP to someone or see them turn a profit off of my work. I wouldn’t want to have someone use my IP for commercial purposes without my involvement. And, thinking about it at the time, I realized that in itself was the heart of the position I’ve wanted to make clear to everyone. For me, the heart of the matter is a belief in two things: I believe that a creator should be able to own and benefit from their own work, and I believe that the culture should also be allowed to benefit from that work so long as it doesn’t hurt the original creator.

It seems so common sense, and for a long time that’s exactly how our copyright system was supposed to work (though, even in the old days, people found loopholes). For a long time copyright followed this sensible life-cycle where everyone got to see a benefit from new works. A creator would hold their copyrights for the majority of their life, their business partners could benefit from collaborations, then after a set period of time it would enter the public domain and new creators could start to take these works in new directions. At the time, the length of a copyright was just long enough so that when someone created something, they would hold the copyright until they had either retired or died. And, while it wasn’t perfect, it was at the very least trying to be fair to everyone: a creator could make a living from their work, but the world could benefit from their work even after they were gone.

I don’t think that the law should have stayed perfectly stagnant – times change and so do the needs of the people – and some changes make perfect sense. In fact, for the most part, I agree to the changes made during the Copyright Act of 1976. Fair use was once actually far weaker than it currently is, despite the flaws that it still has today, and was originally just a common-law doctrine that had absolutely no backing before finally being codified in 1976 in the US. This means that prior to 1976, while the concept of Fair Use existed, there was nothing strictly in writing that ensured a judge had to take it into consideration (and even now, the doctrine is still based in precedent, but at least it’s in writing). Similarly, the extending of life expectancy meant that extending the original copyright term also made sense as well… to a point.

The idea of “life of the author plus…” has always made logical sense to me. The terms of copyright that originally tried to ballpark a life expectancy with a specific number of years was a little inelegant to say the least. But the idea that you own your copyright so long as you’re alive and then that copyright is held by those you’ve authorized for a period of time after your death has always felt fair to me. Of course you should have control over what you created as long as you’re alive and wish to hold that control, and it’s fair that your family or business partners should be able to continue to use it for a couple decades after you pass. I’ve heard some argue that it should only be to the life of the creator, but some cases in the past have shown it’s a good idea for someone’s family to hold onto some rights beyond their life. In fact, without that extension of rights to the family, some people would never have even received credit for their work at all.

Bill Finger is perhaps the most tragic example of someone who would have been completely screwed out of what he deserved without his family holding some rights. Having been instrumental in the creation of Batman and his lore, Bill Finger spent the entirety of his life in relative obscurity, never receiving what he really deserved. It wasn’t until after he died that his family managed to finally get Bill the credit he never got in life and that wouldn’t have happened had they not had some claim to his work. So there are definitely benefits to keeping the rights within the family after a death. But as of late the extension of the “plus” has started to benefit people who may have never even met the author, let alone be related to them. And in the process we’re slowly losing an important aspect of our culture.

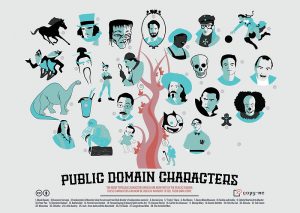

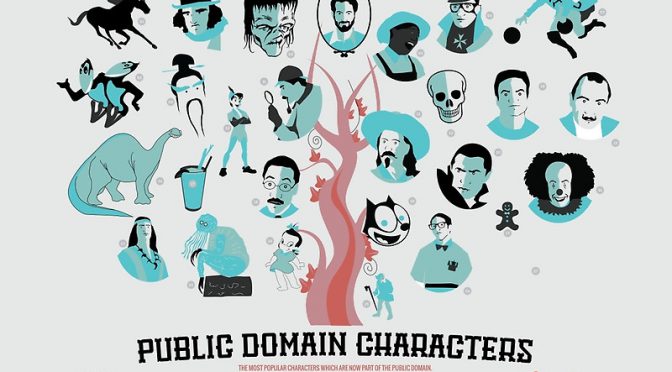

The public domain has benefited our culture in such a profound way that it’s unlikely anyone reading this isn’t fond of at least one thing that was created due to public domain. Fans of Disney movies are likely well aware that the majority of their best material originated in public domain works like fairy tales and older novels. Classical music has continued to thrive into the modern day because those works long ago passed into the public domain, allowing anyone with some talent to play them to their hearts content in recitals, concerts, and recordings. The list of movies, TV shows, and musicals which were based on public domain works is so long that I could spend days trying to find them all and list them here. Could you picture a world where you had to ask permission to write Dracula into your stories? How many people would be put out if Wicked had to be stopped? And yet, under the current laws, public domain has been stifled to the point that there is a very real chance certain elements you know of today may not reach public domain for generations – if ever.

And this really creates the friction that got me talking about this a year ago. As a creator, all I really want to do is be able to make a living off of my own creation and not have anyone take that creation from me without my consent. I simply want the same sorts of lines that Reggie referred to above. But after I’m gone, I don’t see why that creation should be perpetually kept from the public. Yet, currently, that’s what’s going to happen for a great number of elements that should be a part of our shared cultural heritage. And when I commented on it, the first time, a part of me realized that there may never be a time that a work like Axanar will ever be legal. There may never be a time when the works of creators today (or even the last few generations) can become part of the greater culture as a whole.

So to answer the question originally posed to me, I wouldn’t be opposed to fan works (eventually) that didn’t cross the lines Reggie drew above. This early in my career, however, the control of my IP is still very fragile if someone did do something. But once I became established there is definitely more room for such things, and I would be even less opposed to something made long after I died. Though it is entirely true CBS is well within their rights to do what they did, and will be for some time to come, I have this light twinge when I realize the original creator’s been dead and gone for 26 years. At the time Gene Roddenberry created Star Trek, the copyright would have lapsed in the 2020s. As of 1976 it was pushed to the 2040s. Come the extension of 1998, it was pushed all the way to the 2060s. So, as a result, there will be some who hold a monopoly over his creation 70 years after his passing, people who no longer have a direct connection to him or what he made. And, unfortunately, even that may not be the time when it finally lapses…

Because Mickey Mouse’s current copyright is set to expire in 2023.

(I write novels, dabble in screenplays, and post silly stuff on twitter. I hope that the world still sees value in all of this long after I’m gone. Well, everything except the tweets.)

Sadly most people dont respect the public domain or peoples IP, they all go for pirated stuff cause its free. They dont care the consequences that their actions have on the content creators.