In the Alters’ World (and the Agent of Argyre series), creatures of legend reveal themselves to the world. Born through genetic abnormalities, defects and mutations, the Alters have lived for centuries as outcasts of human society, hiding their true nature from the world while colorful stories have been written by many to describe what they’ve seen. But not all legendary creatures can be accounted for by human mutations. Some have been cryptids, misinterpretations of strange beasts or creatures simply lost to time. Though records of these creatures have often fallen to legend, Alter kind has made efforts to preserve the few they can. Today, in the Alterpedia Zoologica, we cover:

The Qilin

A gentle creature with divine grace, the cultures of East Asia tell of an entity much like a cross between a deer, a horse, and a dragon. It is tied to the lore of China, Japan, and both of the Koreas. Leaders throughout history have tied these beasts to their reputation and many have told stories that the appearance of such a creature indicated a time of great prosperity. Known by many names and depicted in a great variety of ways both in paintings and in sculpture, the creature known as the kirin, qilin, and girin holds a deep cultural significance in the most heavily populated region of the world.

But while many creatures have been identified as the possible source of the qilin legend, none precisely match the creature described in legend, leaving one to ask: what was the true origin? Was there an actual creature like this to have roamed the Asian continent? If so, where did they go? And why would someone be writing about them in the middle of December?

Original Tales

Depicted as a chimeric creature, the qilin changes precise description according to the region you’re currently in. Common attributes describe them as the cross of either a horse or deer with the traits normally associated with Asian dragons. They are known to have hooves, a tail, and the body of a hoofed animal (though which hoofed animal is hotly debated, with some seeing them as more horse-like, others as more like a deer, and some depictions even including an ox into the mix). Beyond these more mundane traits, they are also known to have scales, a mane, and antlers – which may either be derived from the association with a deer or with the horns commonly found on Asian dragons. And, while seen to be the embodiment of gentleness, it is often also depicted shrouded in a mystical fire.

In legend they are said to be the embodiment of noble traits in eastern philosophy. The qilin is said to be the most gentle creature in the world, eating only leaves and treading so lightly that it does not even disturb the grass it walks on. It is thought to be one of the most wise creatures as well, often attracted to sages or great leaders. It is thought that the qilin will only appear to those who are meant to do great things and that being approached by one is a sign that you and those around you are to lead prosperous lives. This may be as simple as being the wise leader of a household, or as grand as being someone destined to rule and lead your nation into a golden age. However it manifests, the sight of a qilin is a great omen and many leaders in Asia have claimed to own one or have been visited by one in the past.

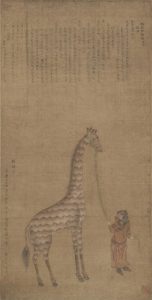

The desire to own qilins by great leaders has, at times, resulted in creatures of a similar nature being brought to noble courts and represented as qilins. Most notably a pair of giraffes were brought back from Africa by Zheng He, a diplomat an court eunuch of the early Ming dynasty. The giraffe’s long legs, graceful stride, and speckled fur coloration made the comparisons to the qilin quite easy, and to this day the word for giraffe in some languages is shared with the legendary creature it was seen to resemble. And, despite the fact stories of the qilin root back to the 5th Century BC, many people believe that the stories of these creatures may have simply been representations of a similar, but otherwise mundane creature.

However, not all believe this to be the case and some continue to hold that the creature was a distinct, purely mystical creature. One example is that, according to Korean legend, the ancient king Tongmyŏng, founder of the Korean kingdom of Koguryŏ, preferred to ride a kirin – something that would be difficult to do with a giraffe. In fact, the ancient king became so entangled with the legend that sites associated with him and his kingdom retain names such as “Kiringul” or “Kirin’s Grotto” – a site near Pyongyang which North Korea claims in their propaganda to establish them as the one true Korea .

Argyre Records

Stories of riding a qilin are not as far-fetched as one would assume. Though nearly extinct in the modern day, Alters have long documented a rare deer-like creature which roamed much of the northern Eurasian continent in the time of Atlantis and the eastern Alter kingdom of Mu. These creatures were known in the ancient times to the Alters by many names from different languages roughly translating to “rainbow deer”. And, though difficult to find in the modern day, specimen still exist in Argyre and other Alter enclaves.

Though not actually possessing scales, or flames, the association with Asian dragons is easy enough for those who have come to witness one. Their range in the ancient times was across much of the northern reaches of Asia and some parts of Scandinavia – where legends of mystical stags eating from the world tree and standing atop Valhalla were shared among the Norse. As a result of living in these incredibly cold ranges, the coat of the qilin is incredibly thick, forming the distinctive mane, and shares many of the properties of the coats of polar bears. Like the polar bears, which possess a clear fur that turns white from light refraction, the hairs on a qilin are structurally colored and refract many different colors depending on the angle they’re seen from – resulting in a distinctive shimmer or sparkle like golden flames across their fur.

Other adaptations have resulted in further extending to their legend. With long legs and a very cautious gate, the qilin is known to walk as gently as possible – a trait they picked up to avoid falling through fragile ice or snow drifts. And, while still quite wild, their natural instinct to avoid direct conflict has made them particularly docile and unlikely to attack unless provoked.

Though they generally maintained their distance, the need for greenery and water led them to the same locations early human nomads would have visited and thus they crossed paths with humans fairly often in ancient times. They were known to be quite aware, however, of the intent of those around them and would generally move to avoid anyone who they felt was an immediate threat. Conversely, should someone appear unthreatening, the qilin was more likely to approach than most animals of its kind, leading to many individuals having stories of direct encounters with these beasts that were eventually deemed to be good omens.

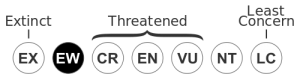

Conservation Status

Unfortunately, the association with good omen and the belief that they could be a symbol of power resulted in many qilin being hunted both to be captured live and be used for their unique pelts by primitive tribe leaders. The hunting of qilin in prehistoric Europe resulted in the creatures being extinct on the continent long before most human tribes could accurately relate stories of the creatures. In Asia they did not fare much better and, by the time of the earliest written records, qilin could only be found in the northeast corner of the Asian continent. By the 5th century BC, when the Chinese first began recording the animals, their numbers had dwindled to the point that most were unsure if the creatures were actually real or not. However, as the Asian leaders saw greater value in taking the creatures alive, efforts to protect the qilin within their borders spared them from extinction.

By the time Tongmyŏng rode a qilin in what is now known as Korea, the creature could only be found in private collections and on isolated islands controlled by the remnants of the Alter kingdom of Mu. The nobles of Mu, having been part of early Asian aristocracy, ensured that a healthy population was to be maintained in regions where the human population was too small to pose a threat. These preserves were managed by their descendants up to the 4th century AD, when a traveler from the west took interests in these creatures.

Having heard stories of bejeweled stags with remarkable grace, a Krampus from the Turkish city of Myra traveled to one of the preserves to see these creatures for himself. Offering to take the responsibility of preserving these creatures, this Krampus took ownership of one small island in the arctic circle where he could build a home and keep watch over the creatures. Though many of the other preserves were eventually overtaken by human civilization, this Krampus maintained his qilin preserve for many centuries to come and remarkably maintained a healthy population. As a result, though the qilin is now extinct across most of the world, in one small island far above the arctic circle…

Saint Nicholas continues to tend to his seemingly mystical, but wildly misidentified, deer.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays. If you liked this little Christmas blurb with a world fusion slant, please follow my twitter where you can get more whimsical nonsense. Happy Holidays!)