Over the last few years there’s been something of a shift in the culture around us. In a day and age where nostalgia properties reign supreme, it’s hard to imagine that the same properties no more than a few years ago were often considered deeply “niche”. Superheroes were considered low brow entertainment meant only for children and basement dwellers before suddenly becoming the dominant movie genre for the last several years. The Lord Of The Rings was once thought to be in the same category, familiar to children and to nerds who spent too much time playing Dungeons & Dragons. Then it became a phenomenon that a studio drove into the ground with an attempt to turn the “prequel” into a franchise unto itself.

Despite this, when you look at the entertainment industry you’ll often find that speculative fiction works still feel like they’re not allowed to sit at the adult table. There is a rush to get some works out even when they shouldn’t because that’s generally what the industry does when they don’t understand a current trend. But if you look at what gets the awards, the recognition, and the respect it becomes clear that we’re still kind of the oddballs. A few years ago I saw several entertainment industry insiders, particularly literary agents, say that sci-fi needed to minimize the “science” aspects to succeed – something they defined as a “new sci-fi”. You’d think the attitude is gone, but on multiple occasions I’ve encountered it again. For all intents and purposes, the current successes of speculative fiction are considered a temporary trend.

Yet, if put on the spot and asked to name a worldwide success in the last 20 years in any form of media, the first thing to spring to mind would probably be in one of those “niche genres”. That’s not true for everyone, and you may certainly associate “critical acclaim” with “worldwide success”, but when you think of a true phenomenon it will almost always be something that is marginalized by the same critics. Sometimes it’s argued to be a matter of “depth”, but some of the deepest stories that spring to mind are also within those genres. It’s a disconnect that sometimes makes you wonder:

What do the niche genres have to do to be acknowledged as not actually being “niche”?

Overcoming Our Label

When you really think about it, the fact that speculative fiction works are treated like a form of entertainment with limited reach and scope is a bit of a paradox. The oldest known piece of English literature is Beowulf, a story about a man fighting monsters that essentially has all the hallmarks of modern fantasy but was published in a starkly different era. In fact, for all intents and purposes, any written work predating the Renaissance would now likely be classified as a fantasy work today. Sure, they were generally thought to be mostly true at the time, but it doesn’t change the fact that the hallmarks of those stories now firmly fall into the epic fantasy genre.

Meanwhile, science fiction has long addressed things that may not be true today but are likely to be true tomorrow. Decades ago, the ideas of computers small enough to fit in your pocket would have sounded like flights of fancy. A century ago people thought that going to the moon would be next to impossible. Even today, some people still think it was impossible despite all evidence to the contrary. And yet these were stories told years ago by people who were paying attention to where science was going and what some of the smartest among us were saying could one day happen. Sure, sometimes it was blind guesswork, but often it was educated and thoughtful.

For a long time though, there was this general field of exclusion that haunted the speculative fiction genres. For years it was usually seen as the domain of children to read anything involving something that wasn’t purely human. Whether it be fairies, aliens, or cyborgs, the idea was that these entities were not real and thus were purely “works of imagination”. Despite the fact that all fiction is a work of imagination, this generally meant it wasn’t “respectable”. And that lack of being “respectable” usually meant it was looked down on and left out. As prestigious as Hugos, Nebulas, and Saturns are within our community, I’ve had to explain what they are on more than one occasion to speculative fiction fans and writers. In fact, one friend off-handedly said they would never be in real consideration for awards because of their genre before I pointed out to them that such things existed.

And it’s conversations like that which remind me that there’s still a bit of a barrier between us and the “mainstream”.

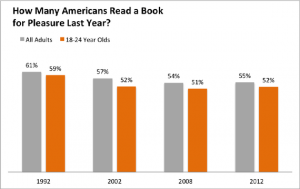

Though speculative fiction writers can easily hold up the triumphs of our genres, when you think about them more you realize the pigeonhole we’re in. Works like Harry Potter, Hunger Games, and (though I hate to say it) Twilight have a great deal of reach, being translated into dozens of languages and being read by surprisingly varied audiences. But Harry Potter was still written for and marketed to children and the YA genre and all of its successes are directed towards teenagers and college students. Rarely do you see that kind of success come out of an adult oriented novel with similar genre conventions. And, while it would be easy to say that it’s because adults read less, it’s actually not true since adults tend to read more than teenagers and kids.

But then what do those adults read? Given the success of speculative fiction in books, movies, and television – they’re apparently okay with reading and watching the stuff that we normally aim at kids. In fact, we’ve all seen several older fans of these younger books and we’ve also seen other adults shame them for it. One article I’ve read in particular pointed out that 28% of all YA sales are from people in their 30s and 40s – then roundly shamed them for it. And while the article in question happened to focus on “realistic” YA, the figures were about YA in general – and the biggest speculative fiction successes are YA. So we have to accept that at least some of the momentum to those books is from adults who choose not to be shamed (or are good with it being their guilty pleasure).

And the reason is simple, that’s basically where you can find the speculative fiction works that are going to receive the full might of an advertising push. Marketing is heavily influenced by targeting the correct demographics and it generally has rules that can be seen as pretty arbitrary. What’s the difference between a 34 year old and a 35 year old in terms of personality, lifestyle, and interests? Don’t worry, I don’t know either, but I’m sure a marketing executive somewhere would try to argue it to the death. And, because of this, works that have traditionally been targeted at younger audiences will continue to be targeted at younger audiences. So, as a result, there’s always a bit of a resistance against the idea of speculative fiction being aimed at adults.

It’s not that adult oriented speculative fiction doesn’t exist, it most certainly does, but rarely does it get the same kind of media blitz you see behind other genres and demographics. Game of Thrones has taken the world by storm in recent years, so you would be forgiven for not realizing that it took 15 years to end up on the New York Times Bestsellers list. Originally published in 1996, “A Game of Thrones”, the first book in the “A Song of Ice and Fire” series, didn’t reach the New York Times Bestseller list until 2011 – the year HBO put its might behind hyping the property. A critically acclaimed, award winning series of books with a passionate fan-base – treated as niche until someone decided it wasn’t anymore.

This resistance is less pronounced now, especially since the success of Game of Thrones, but it still kind of exists. Despite all of the successes that speculative fiction works have had, there’s still that feeling like it’s all a bit of a fluke. The fact is, the figures seem to say the opposite. Speculative fiction works have, time and again, demonstrated the ability to really capture massive audiences. Yet when you look around there’s clear indicators that the entertainment industry is “hitting the iron while it’s hot” – doing their best to get as much profit as possible before it cools. And, thinking hard on what exactly would be the cause, it occurred to me it was because of another time the industry hit the iron while it was hot.

Back in the day pulp fiction was a major source of quick and dirty profit for publishers. Not particularly requiring depth, they were easy to write and get out quickly and to an audience that wasn’t very demanding. Full of action, adventure, and shallow plots, pulp was mostly the domain of children and teenagers. But eventually those children and teenagers needed a little more variety, and the easiest way to give them that variety was to throw in the trappings of speculative fiction. First, they started to take the stories of pirates, bandits, and lost civilizations and started to throw magic. Then, they started to tell stories of those in the far flung future. Sure, it was essentially the same story, but now it happened in space. And it totally worked, so much so that Pulp SciFi paved the way for the eventual Golden Age.

But those stories were basically aimed at immature audiences, and when that worked the industry just kind of got stuck in that mindset. Marketing is generally about figuring out what audiences will buy something and then targeting them for all they’re worth. So every time kids and teenagers supported speculative fiction, it became deeper entrenched that those were the people we should be targeting. And this is part of why a lot of speculative fiction writers have a love-hate relationship with our more immature roots. We don’t want to be just for kids, and we often talk about how we need to be more mature to avoid that. But, as I’ve said before, I don’t believe we should distance ourselves from our roots. Instead, I think there’s a need for everyone to recognize that people still enjoy these stories well past their 20s – even if they’re told not to.

What can any one of us do about that? Not a whole lot. This isn’t exactly something we can control since such mindsets are hard to change, but it is something to keep in mind. Especially in today’s day and age, when so many of us are not just the writer but also the marketer, it’s important to try to keep in mind that there are still people who might read our works beyond that younger audience. I know out the gates that most of my work will find a comfortable place among people in their 20s and 30s, but I realize now that it’s probably a good idea that, if I see the opportunity, I shouldn’t be afraid to get it in front of people in their 40s or 50s either. Maybe it won’t get me any sort of prestige, but opening up to an adult audience…

Can work if given the opportunity.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays. Someday I may be mainstream, but for now you can like me before I was cool by following my twitter.)