If you read or watch enough science fiction over time, there are certain tropes that tend to appear almost everywhere. Most of them are centered around external forces that provide a mirror to look back on ourselves. This alien world happens to be populated by a race that has an extreme philosophy that mirrors one of our own. This other creature we thought wasn’t intelligent has made us question our prejudices. These seemingly natural phenomenon are trying to communicate with us, making us question the nature of life itself. Sometimes these tropes will fall into cliche if done improperly, while they tend to say something of value if done correctly. But not all of these mirroring tropes happen to be external forces – sometimes they’re man-made.

Our own creations, or things that we do to ourselves, are often good reflections on what kind of people we are and what’s important to us. When we’re writing stories of artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, or science run amok, we tend to show not only our general motivations as a species but also our fears of our own ability to screw it up. However, there are other tropes about things that we create that are much more mundane in concept but still give us just as much of an insight into what we hold important. And, lately, one of those fantastic but strangely mundane technologies has been catching my attention more often -virtual reality.

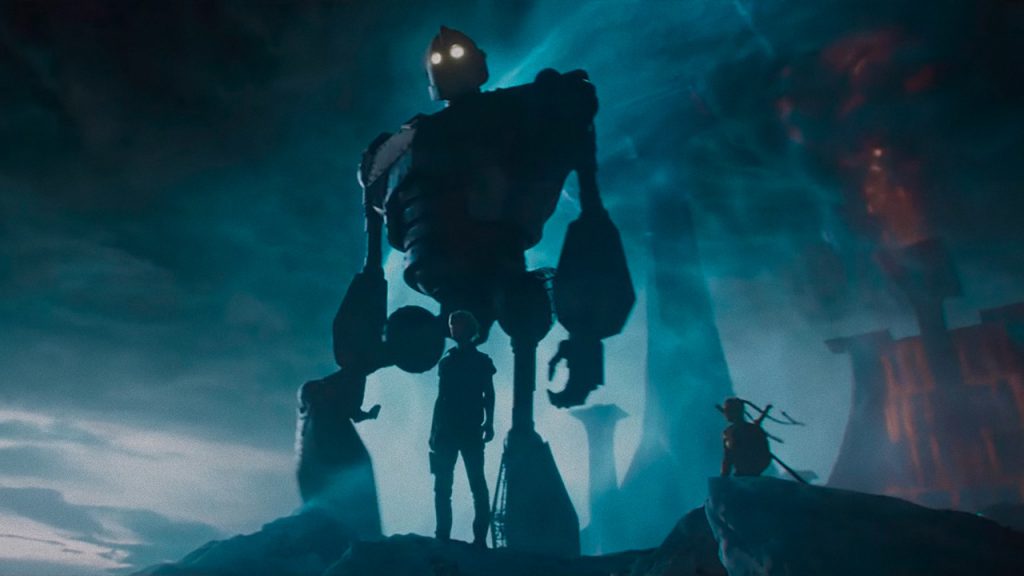

When I say virtual reality I don’t just mean VR headsets but just about any technology that happens to simulate a different world for us. From the VR gear in Ready Player One to the holodecks on Star Trek, there’s a wide variety of approaches in sci-fi that reflect our efforts in the real world. And, despite how fantastic it may sometimes appear, we’ve been making great strides in this technology in the last couple decades to the point that a lot of graphics cards and game consoles now have VR support built right in. But while our real world vision of how to use VR can be a tad stunted from time to time, generally reserved for gaming, the world of sci-fi has shown us a variety of other uses that we only briefly touch on here in the day to day.

And, it’s strange, because when I look at the potential of fully immersing in fictional worlds, I actually think traditional video games are the least likely to take the lead…

Recreational Recreations

For as long as there’s been fiction there’s always been some desire to become immersed in the world portrayed within. In the days where our medium was restricted to just pictures and the printed word that immersion was limited to our imaginations or, if you were lucky, a stage adaptation. But as technology has progressed we’ve found more and more ways to make that immersion more accessible to everyone. The invention of film allowed physical adaptations to be mass produced in a way that stage adaptations just couldn’t be. With the introduction of television, those mass produced adaptations could be displayed right in the home. But the desire to actually participate in the ongoings was never quite satisfied – so of course we were going to start trying to make it interactive.

The earliest video games didn’t have anything resembling a plot, most of them were what we would consider “casual” games today, but it didn’t take us long for us to start trying to change that. With the creation of Colossal Cave Adventure in the 1970s, the “Text Adventure” genre was born and video games started on the path to achieving that dream of actually being a part of the story rather than just a bystander. Decades later, video games have gone from being simple pixels on a screen and a series of scripted text responses to being complex narratives that now play out more like interactive films. In a video game, you get to be the hero of the story, and in the last couple decades they’ve been making more strides in letting you decide just what exactly that means.

So it would certainly make sense that, if anything were to make that transition, video games feel like the most likely to dominate the realm of virtual reality. They’re already doing the most to create fully interactive fictional worlds and the skills required to do that are pretty much tied to the industry right now. Sure, there are plenty of digital effects artists in the film industry, but few of those artists have to create entire worlds and the physical laws within them from scratch. To find the teams with that skill set, you almost exclusively find them working on video games. And yet, while they’re the industry most likely to try VR, history has shown that traditional video games and virtual reality have a really hard time coexisting.

If you look through the history of video game peripherals over the last three decades you’ll find dozens of attempts at increasing player immersion that just didn’t pan out. The most visible of these trends right now is the recent reintroduction of virtual reality headsets, but just a decade ago all of the same companies were trying their best to make motion controllers a thing. And, while some casual observers would think the Wii was where motion control first caught on with the industry, the truth is video games have actually been trying to use motion controllers of one form or another since at least back in the 1980s, with examples of home console motion controllers like the Sega Activator being available for the Genesis back in 1993. And as for those virtual headsets? Let’s just say everyone learned some painful lessons about that around the same time.

And the reasons why things like the Virtual Boy, Sega Activator and even Nintendo’s Wiimote never take over the entire market the way everyone thinks they should tend to be the same every time. The fact is, no matter how much we may want to be in the middle of the action, being a protagonist in a traditional video game is disorienting, painful, terrifying, and exhausting. Virtual headsets in general have had a notorious history of making people dizzy, nauseous, or becoming a little too real for comfort (i.e. It’s one thing to stand at the top of a skyscraper in a video game but it’s another to actually feel like you’re standing there personally). And to add to that problem, as much as we take all of it for granted with a controller in our hands, most of the actions taken in video games are damn near impossible in the real world and, unfortunately, our bodies are in that real world. After all, only in the world of video games can a chubby dude in overalls jump 20 feet into the air from standing.

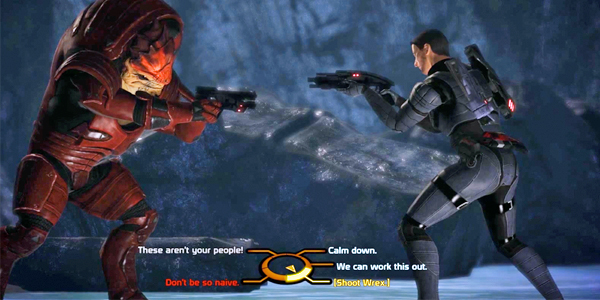

So, while you can compensate for the player to a degree, the jump into a fully immersive artificial reality for recreational purposes probably needs to be something less dizzying and physically taxing. You’d need it to be within the realm of physical possibility without being a world class athlete while still having the player feel like they’re making an impact on the story. And there are games that actually follow this model, but they tend to be on the fringe of the market and sometimes aren’t even really considered “video games” by the industry or its fans. Rather, many of these fall into the domain of what is known as the “visual novel” – a genre fairly popular in countries like Japan. And, for those familiar with the likes of Star Trek, that may sound pretty similar to a “holonovel” – which is where I think the medium is really destined to go.

Though the idea of the “holonovel” always felt strange to me as a kid since it always felt more like an RPG than a novel to me, I’ve come to realize that it actually makes a lot of sense when you consider those visual novels. The chief difference between visual novels and other video game genres is the level of emphasis on different aspects of the gameplay. Within a visual novel, the narrative aspects are the core mechanic while everything else serves to support it. This is almost exactly how it works with holonovels too – you’re there to play through the narrative while the gunplay, sword fights, and whatever else you might have is there to push the narrative along rather than being the point. Sure, Dixon Hill had to use a gun a couple times and Sheriff Worf had to win a duel against a bandit that looked like Data, but the point of both of these was just to play out the character arc (much to Worf’s chagrin).

I think the missing link between modern VR entertainment and these sorts of virtual novels is actually a matter of scale. As it’s become easier for smaller teams with fewer resources to make games on their own there’s been a surge in indie games that have taken more risks with genre conventions, and it’s only a matter of time before the same happens with VR as well. Bigger companies, focused on more profitable genres, tend to build the tools necessary for smaller teams to follow in their footsteps through the creation of engines that those smaller teams can eventually use. And, as the engines become more versatile and intuitive, the sizes of those teams can shrink down until eventually it becomes profitable to start churning out these virtual novels. Before long, as it becomes more profitable, the number of teams dedicated to such productions would grow until eventually the industry finally shifts towards these sorts of productions dominating the medium.

But, in the meantime, there are a couple compromises that will likely have to be taken. First, the video game establishment is probably going to have to take the lead on developing those tools, so we have to accept that the early industry is going to be dizzying, uncomfortable, and physically taxing. Second, those early teams to take the tools are going to have to go through a great deal of trial and error to get the right mix for a good experience so we’re probably in for some stinkers. But third, something that might not really be a “compromise” for some, early indie projects will probably need to follow more profitable fringe genres from time to time to get seed money for their dream projects. Or, to put it more bluntly…

We’re probably in for a lot of erotica.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays. Follow me on twitter, where you can see just how out of touch I am with reality every single day.)