A while ago someone asked if there were any things in mythology which were completely untamed, could not be captured, could not be stopped, just wild and perpetually free. They could think of one themselves, but couldn’t think of many others. And, with some careful consideration, I realized the question appeared simple but was deceptively complex, ultimately answering, “no, not really.”

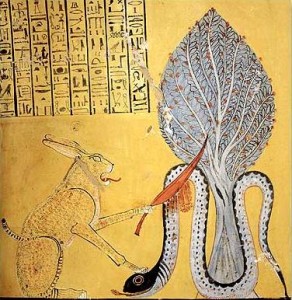

That’s not to say there aren’t beings of chaos in mythology, there most certainly are. But often you find that those beings of chaos are overcome or controlled by others around them. Loki is bound beneath Jormungandr until Ragnarok. Eris is a minor deity in the Greek pantheon, repeatedly stopped or overcome by those that encounter her, left to make grand impact only by tricking others into doing it for her. And Apep, god of chaos in the Egyptian mythology, was the mortal enemy of Ra – who made it a point to attack him every night upon his return to the underworld.

While mythology often talks about what humanity is afraid of, it doesn’t often leave these forces completely unchecked. In a somewhat optimistic fashion, the mythology of the things that we’re afraid of also tells of how we overcome these things. It’s the kind of thinking that has people make offerings to volcano gods or begin ceremonial dances to call for rain. We like to believe that we can survive whatever nature brings at us and that those with just a bit more power than we have can defeat those forces altogether.

And this optimism comes not just from our desire to survive, but also to overcome the forces that keep us down – both external forces and, often, internal…

The Metaphor Of Enkidu

One of the common themes in mythology isn’t just metaphor for what we’re afraid of but metaphor for what we are trying to control. Often these are the same thing. Even the construction of cities is to control the wilderness so that we can survive things which previously had control over us. We couldn’t do much to keep bears out of a small village, but a city is a far more frightening thing to the large furry murder machines.

And one of the forces that we fear most and feel we have the least control over is ourselves. When faced with decisions that we know, objectively, are not good things for society or ourselves, we will often take the darker path regardless because of our inner demons and the hint of instinct gnawing at the back of our brains. We’re prone to doing things for lust, greed, and anger that we would say in another state were horrendous. So, of course, we often find that stories in mythology revolve around this idea of human frailty being the cause of our ills.

The Iliad and Odyssey were spurned by human weaknesses and indiscretions – Paris choosing Aphrodite for the sake of having Helen and Odysseus revealing his identity to the son of Poseidon after blinding him. All the world’s problems were released from a box because Pandora chose to look inside. Stories of creatures such as Succubi, Kitsune, Yuki-Onna and the like often involve people being led to their deaths by their inability to control their lust. And, of course, Adam and Eve ate the fruit and were kicked out on their asses for their trouble.

But while these aspects of ourselves and our environment are often in opposition to us, they are not necessarily bad things. One of the greatest examples of this is the story of Gilgamesh and his companion Enkidu.

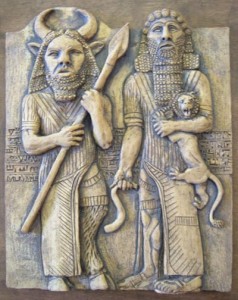

Gilgamesh was a powerful ruler of the kingdom of Uruk. As a demigod, he had great power and was responsible for raising the walls of the city himself to defend his people. But, while Gilgamesh was a powerful ruler who was responsible for protecting his people, he was also quite harsh and strict on them. In his quest to protect his people he became a ruler the people did not believe was really there for them, he had essentially lost his humanity to his authority. Needing a way to calm him, the people prayed to the gods for a way to end Gilgamesh’s harsh attitude and bring him back to the people. In response to this, the gods created a rival for Gilgamesh: Enkidu.

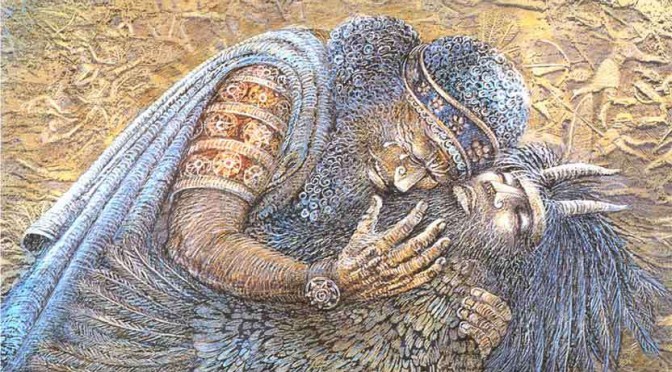

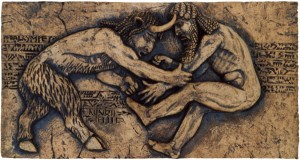

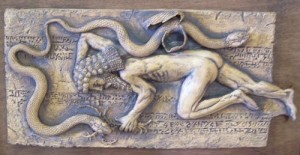

Enkidu was everything Gilgamesh was not. He was raised in the wilderness, isolated from the people, uncivilized and untamed. He was as powerful as Gilgamesh, but lacking any knowledge of the human world. He had no authority, he had no responsibilities, he was as wild and free as animals were. And, upon hearing of him, Gilgamesh sought to tame this wild man and introduce him to the civilized world. Sending a woman into the wilderness to show Enkidu the benefits of human society, Enkidu was lured by this woman out of his wild ways and brought to join the people in civilization. There, Gilgamesh and Enkidu became great rivals, wrestling for superiority until Gilgamesh proved himself the better. Afterwards, they became fast friends and great heroes of the people, setting out on adventures together and making each other better than they once were. Gilgamesh was no longer cruel to the people and Enkidu was no longer wild. Together, they were whole.

There is a powerful metaphor in this encounter that rings true throughout time. Gilgamesh’s cruelty has long been echoed in the saying that “power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” But meeting Enkidu reminded Gilgamesh of his roots and reminded him of his true self, reconnecting him with a simpler part of himself that was lost in his title. Enkidu was the very representation of the wilderness and the wild nature within mankind, and only by taming him and accepting him did Gilgamesh become a better person. In fact, even as they were friends, Enkidu continued to confront Gilgamesh with the truths of his nature and the things he was afraid of – including death.

Faced with great dangers while adventuring together, Gilgamesh tells Enkidu that he’s bitter towards the gods for being the only things which do not die. He feels cheated by the concept of death, unwilling to accept it as his eventual fate after all he has done. But the gods, hearing Gilgamesh’s complaints, strike down Enkidu in a painful, inglorious fashion. Gilgamesh watches his friend die, and Enkidu, in his final moments, accepts his death while recognizing the great journey of his life.

But, once again, Gilgamesh and Enkidu came at everything differently and, faced with the death of his friend, Gilgamesh began to seek out immortality and the means of avoiding the same fate. Through many adventures he tried to obtain a means of living forever, seeking out others who had lived far longer than he and defying the will of the gods. Eventually, despite his efforts, Gilgamesh returned home and fell ill, slowly dying as the gods determined his fate. There was some debate among the gods, given Gilgamesh’s many deeds, whether or not he should be granted what he sought, but it was decided that he should not be any different from the mortals around him. Instead, he was made to realize the true purpose of his quest. He hadn’t been seeking an answer to death, but rather the value of life. He had obtained immortality through his deeds and the impact that would be left by them. And, like his friend before him, Gilgamesh finally accepted his death while realizing the value of his own life.

This is why you won’t find any truly untamed forces in mythology. You won’t find something that is never beaten or overcome, because mythology and literature aren’t there to tell us about the inevitability of our death and the powerlessness we have in life. Mythology is there to address our fears and tell us that there is still value in what we do here and now. And, more importantly, mythology tells us that some things we fear are things we need to accept about ourselves if we are to be the kind of people we are meant to be.

The metaphor of Enkidu has lasted forever and been duplicated throughout time with rivals and companions mirroring the protagonist of a story and showing them parts of themselves they aren’t necessarily comfortable with. This isn’t just to create good drama, but to also represent our very need to deal with our own desires and worst natures if we’re to live life to its fullest. Just as Gilgamesh had to overcome and accept Enkidu to become the kind of king who would live on in the memories of the people, we have to overcome our fears, anger, and selfish desires to become the sort of people who will be remembered fondly when we are gone. This is usually represented as an external conflict, but in defeating or befriending that external force we find our heroes better as a result.

It’s not something lost on us today, many writing classes teach their students that the best villains are people who reflect something about the hero. But it doesn’t necessarily have to stick to just the villain either. You’ll find some of the best friendships in fiction are formed between people who have the most differences but are united by similar goals and ideas. The Enkidu effect can be seen in something as complex as the psychological motivations of our heroes and our villains, or in something as simple as two heroes from vastly different backgrounds coming to an understanding that they need each other for the greater good.

We need to see the wild and untamed become tamed. We need to know that our lives matter in the grand scheme of things and that means we can’t just tell a story where a force is left unchecked and beyond our control. Honestly, we see enough of that in our own lifetimes as we struggle to get ahead and find ourselves constantly beaten down by forces far beyond us. Some would applaud a story for having the courage to reflect our real lives to the point that the hero may die, but how long can that last before it hits too close to home? Despite wanting something that more closely reflects our lives, we also want that reflection to show that everything’s still going to be okay and that we can become better people as a result of our trials and tribulations. We want to know that it’s possible to overcome adversity, we want to be able to overcome our inner demons, and we want to see chaos defeated…

By people just as flawed as the rest of us.

(I write novels and I write tweets. Both of these are good times and show people overcoming things. The tweets are mostly me overcoming my lazy.)

Great post and interpretation of Enkidu’s myth. My best compliments 🙂

Ciao, Luca