A few years ago I named this blog as a tongue-in-cheek reference to my sometimes crippling allergies. While many people get simple hayfever over exposure to certain particles in the air, I’ve been known to have flu-like symptoms and migraines. It’s not completely horrible, however, since the combination of these allergies and my medications either puts me into deep sleep with vivid dreams or a half-awake, half-dead zombie state where I daydream constantly. This would still be horrible for most people, except I am a professional bullshit artist (writer) and these dreams sometimes inspire new ideas. For someone who lives a fairly sober lifestyle, this is a momentary glance into the kind of hallucinogenic state that inspired Mary Shelley, Jules Verne and whoever came up with that Charlie Sheen character.

The problem is that working on something serious, such as this blog, is almost inconceivable when in this altered state. I give it my best shot but at a certain point I’m incapable of tasks such as research, assembling random facts into a coherent form, and most especially making it readable. So, while I had plans for the end of last week and the beginning of this week, I’d forgotten that the whole country was going to dump one mighty fuckton of smoke into the atmosphere all at once.

Point is, plans change and instead of trying to tackle more African mythology as part of the continuing Alternative Mythologies series today, I’ll be writing about one of the few things I could think about in the last few days…

Structure and Pacing

Pacing is something that writers live and die on in this industry. Not everyone can agree on universal definitions for “good” and “bad” stories, but what everyone can agree on is that if you fuck up your pacing…

A lot of the professional and semi-professionals I know out there stress about this constantly. But what really baffles me is that the curriculum for writing programs I’m familiar with almost always approach pacing from the wrong direction. The three act structure, for instance, is taught almost universally as this first step towards creating a coherent plot. The problem is, as many people eventually learn, sometimes three is the wrong number of acts. As one of my friends said off-handedly, “sometimes there’s seven.”

This creates a conflict for people who had been taught the three act structure as a sacred tenet of the writing profession. If you’re told that every story must have three acts then when it comes time that you realize the three act structure doesn’t exactly fit what you’re writing – you’re screwed.

But that’s because the way we teach writing is backwards, you start to learn to put acts into your writing without people understanding how and why “acts” exist. Some people think it’s an outline but it isn’t, it’s just that three acts happen to coincide perfectly with something that does exist almost universally: logical progression (beginning, middle, and end). That brings us to the great problem: most people don’t understand the basics of structure…because they were taught a more sophisticated structure and told it was the basic one.

So let’s take a look at some of the structural standards and why they aren’t universal, starting with…

Acts

This is often taught to everyone as the most basic structure of any story. The “acts” structure has been taught since the written word more or less, and everyone has this vague understanding of what it is. However, I challenge you now to define what an act is to yourself without being vague.

It’s hard, isn’t it?

That’s the first mistake of teaching acts as the basic structure: “acts” aren’t a tangible element outside of their origin. The first form of story telling was oral tradition, people would tell their stories in person and would preserve them by teaching them to the next generation who would then tell them to the generation to follow. Over time, this evolved, the stories beginning to involve props, costumes and multiple players. And this evolution eventually became a genre unto itself known as “plays”.

So as the written word formed, this ancient tradition gave birth to the first “fiction writers”: playwrights. The playwrights had a task ahead of them that was unique at the time. Most story sessions were short, discussing only a small event that could be told by a single person over the course of a few minutes to possibly an hour. But plays are more complicated – they require many moving parts and could last much longer than the short stories told around campfires in the past. So playwrights came up with a structure that helped them in multiple ways: acts.

The act, despite the vague notion it somehow associates directly with the concept of “beginning, middle, and end”, is really a chunk of the play that exists between intermissions. Consider for a moment when you watch a play, the curtain falls and they stop the entire play for a period of time. Why do they do that? What could possibly the function of stopping the story in the middle of showing it?

Well the first function is a practical one that has existed since the dawn of human civilization: the audience gets antsy. Sitting for hours at a time in dead silence is not something we’re actually wired for. In our modern day context, we have the ability to take these stories in while still being somewhat free to move or keep ourselves busy beyond watching someone else. Consider how often you leave a room while watching something in your daily life. Realize that you’re not allowed to move, speak, or make noise which may disrupt the actors on stage. One moment of being distracting can ruin the entire thing for everyone. So somewhere, deep in our brains, a small primitive voice is yelling to us, “We gotta move! Gotta go! Let’s go! Hurry! Shit’s trying to kill us out there!”

It could be too much for us to handle if we had to take an entire play without a moment to breathe.

The second purpose of acts was practical for the actors: It takes time to get changed. When that curtain falls the actors have a chance to get into new costumes, make minor adjustments and allow any set changes to occur. This is something that couldn’t be done so long as the curtain was up and they were on stage, and with a more complicated story it’s vital that you do it. After all, without such a change, all plays would exist in a single location taking place over real time. If you consider it, how many interesting things could happen in only a few hours of someone’s life? Not a whole lot, right?

And that brings us to the third function of the intermission: progression of time. As the curtain falls, you’re making a mental note that time will progress and that when the curtain rises again you will not be at the exact same moment of the story anymore. This allows you to skip through the timeline, to get the audience to recognize that two scenes aren’t the exact same scene. This one trick, stopping the play, is absolutely vital for telling a story live in front of an audience.

So when you don’t have a live audience, some of this utility disappears. This is most particularly true in…

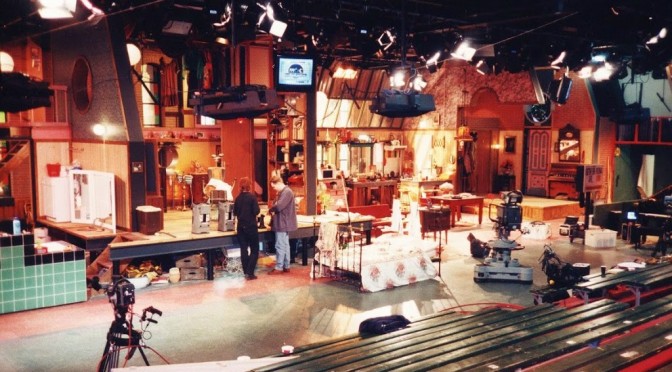

Film and Television

Outside of plays, intermissions fade away. So why do we keep teaching “acts” to new writers? The simple answer is that the first novelists were playwrights, the first screenwriters were playwrights, and the first teachers were (say it with me) playwrights. In fact, for film, the pull of the playwright mentality was so strong that earlier films, when they started to get longer and more complex, still had intermissions! For early film this made sense for several reasons:

- Intermissions allowed the projectionists to change the film reel on the projector

- Intermissions allowed the audience to go to the concession stand, which provided extra (read: the majority of) profit to the theaters

- Intermissions allowed an audience that was used to the play structure to do what they would normally do in the gaps

This faded over time as film projection started to become a more seamless process and audiences got used to the new environment. No one had to worry about interrupting an actor on screen, so you didn’t have to be as strict. And because it didn’t have to be as strict, it became far easier to ignore that voice in the back of your head.

Television, meanwhile, can still use the act structure, but the intermissions there are more plentiful for a different reason: commercials. This is how a three act structure starts becoming five, six or even seven acts over time. As a television writer, the objective of your pacing above all else is to make sure that the story between the commercials is compelling enough to make sure that people come back after the commercial break. So that means you have to end every “act” with something that will make people want to come back after someone has tried to sell them something unrelated. This too, however, is beginning to fade away as streaming becomes more common.

Shows will soon have to be written more like short films and less like a television play. This could be a problem seeing as film still doesn’t exactly have a structure of its own. That’s not to say that there aren’t some formulas which work, but film’s flow is a different beast (that I’ll tackle in a later entry). And, if you ever want to see how hard the jump can be, you can just consider how many things worked well on television that didn’t quite pan out in film.

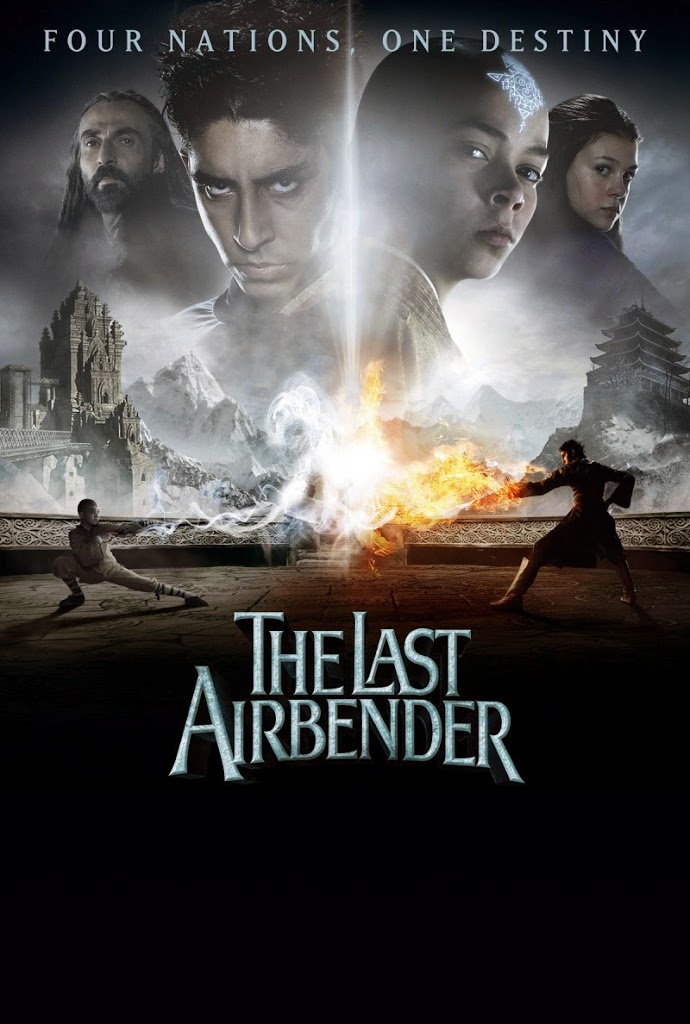

|

| Though sometimes the problems are more extensive than adaptation decay. |

It’s these differences which you have to keep in mind even though the basic premises of all story telling are somewhat universal. I once told a friend of mine that it was beneficial for writers to take at least one acting class so that they could actually live in the minds of their characters for a period of time. I took one myself and it helped greatly in letting me put myself in someone’s shoes when I write for them. But the idea seems somewhat foreign to a lot of people. In fact, my friend replied that taking a class and acting out a play on stage weren’t beneficial to someone who wasn’t a playwright because “the formats are different”. Yet, if this is true, why is it that you still learn their structure?

The truth is, while the basics of storytelling are universal, the “act” structure doesn’t apply to many forms of writing anymore, it’s just the way teachers approach it because that’s how they’ve been taught to do it. But if you look closer you’ll realize that older forms like prose actually follow a different structure. Because, after all, novels have…

Chapters

One of the questions I’ve been asked in the past is “how many chapters are there to an act?” It makes sense, if you’re taught that there are three acts to any story then you’ll start to believe that there should be a certain number of chapters within an act. But this would be wrong if you consider what I just explained about the nature of acts above. If you consider their purpose and how they move the pacing of the story (major progressions from one part of the story to the next that occur when the curtain falls), then the answer to “how many chapters go into an act” can have one of two answers: “one” or “none”.

Chapters for prose fill the exact same niche as acts in a play. When you hit the end of a chapter, your brain is taking a minor intermission period. This could be the time when you stop reading for the day. It could be the time you get a drink before you start again. It could even just be a time when your brain says “what comes after this is different from what just came before”. You rarely find solid scene breaks without a transition within a chapter, you won’t have a character standing in an office one page and a house in the next without some sort of transition you follow him through. But if you put a chapter in there, that transition can happen instantly without the travel time in between.

|

| Or the need to drive the car directly into the living room. |

You can also use chapters to dictate shifts in tone and substance. If one chapter is more light and focused on a conversation, changing the chapter tells the reader that the light conversation time is over. It is almost like a form of macro punctuation that we understand on an emotional level but rarely on a cognitive level. And that, for new writers, can be a major pitfall because they don’t realize what chapters do for and against them.

One recent example that I came across was that of a friend who has been working on a novella. He came to me saying that his story felt too rushed and that he believed he was going too fast towards this event that he wanted to happen. He had an outline and he had consulted with another mutual friend for their opinion, but he couldn’t quite see why his story’s pacing felt uncomfortable. So I asked him how far along he was and he replied, “Chapter 10.” Knowing that not all chapters are a universal length, I asked him how many words in he was and he replied, “About 12,000.”

Consider for a moment that the standard for printed prose is approximately 250 to 300 words per page depending on font size, page size, and formatting. My friend, who had gone 10 chapters into his story, had an average of 3 to 5 pages per chapter. This was definitely a contributing factor to that pacing issue he felt. Anyone who reads enough knows that the size of your chapters is essential to pacing – two chapters at 30 pages just feels like an easier read than one chapter at 30 pages. This is because our brain is looking for that intermission so we can appease…y’know.

So when we see a short chapter we feel like that chapter is very fast and breezy. If you have too many of these chapters right next to each other the progress starts to feel way too light and fast. It’s not a problem people often run into, but it is possible to make your story so easy to read that it becomes nonsensical to the audience you’re trying to reach. Picture if the plays I talked about earlier had the curtain fall every 2 minutes. After a bit, you’d stop caring even though the scenes are going quickly because it’s almost stuttering the entire time.

And that’s another reason that the act structure doesn’t work as the “basic” storytelling structure. Chapters serve a similar function to the original acts, but someone could work with three acts in mind for a novel and then overlook the fact that their chapters aren’t paced correctly. The chapter pacing is going to screw up the story even if someone perfectly paces it in regards to the three act structure they’d followed their whole lives. So remember, your breaks in the story serve an actual purpose and the acts are not just an outline, they were a functional part of story telling for a unique format that required them. After all…

Even these two require the curtain.

(As you know, I write books. For the next few days I’ll also be writing about these pacing issues because, despite how long this went, it actually took less new research than what I was originally going to do.)