Pacing is the lifeblood of what we do as writers. Though there are a lot of ways to make your work sink or swim, poor pacing is one of the most common errors a writer can commit. The old critique that it felt “too short” or, worse, “it never ended” is one that echoes in the dark recesses of our minds. To really progress from amateurs to professional writers we have to ensure that we understand the idea of pacing and how it interacts with audiences on a fundamental level. Though we’ve evolved intelligence, deep down there’s an animal instinct that’s hard to fight.

Too fast and the audience can’t follow, too slow and the audience gets bored. On the surface, these look like two very different problems. But both of these directions often have the same root cause: a misunderstanding of the nature of pacing.

In my last entry I covered how the most commonly taught format for story telling, the three act structure, is actually a product of its origins and may not actually be the “most basic form”. As I described there, novels long ago picked up a structure of their own that worked better for their format when they created chapters. The pacing of a novel depends upon getting a good feel for the length of chapters. The pacing for a comic book depends on understanding that each panel is its own moment in time. The pacing of plays and television shows depend on building acts which peak just in time for the curtain to fall or the commercial to break.

What about the pacing of film? What does film really have to provide it a steady structure? Well for that you have…

The Beat

When playwrights first came to the form of screenwriting, the three act structure was a thing, but it wasn’t THE thing just yet. It was screenwriters, working from what they knew in their background, who started to make the three act structure vital to the creative process. It helped them figure out the pacing of their story when closing the curtain for a set change became unnecessary – intermissions still happened, but as I pointed out before, for other reasons. The writers’ intermissions were no longer determined by the flow of their plot and their pacing, it was determined by technical limitations. So what they did was create a structure so easily defined that someone could actually draw it.

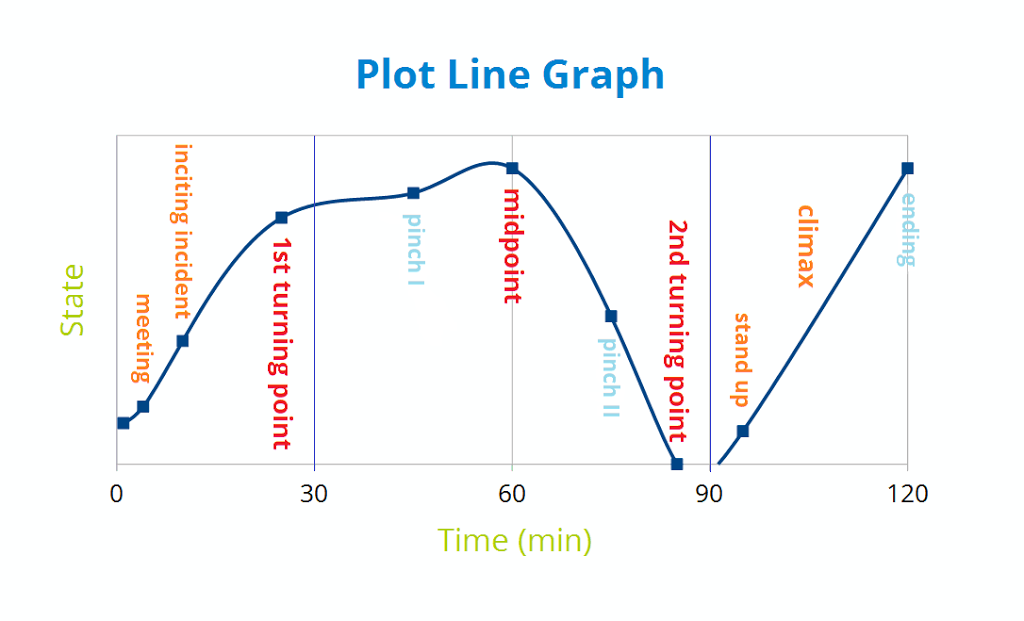

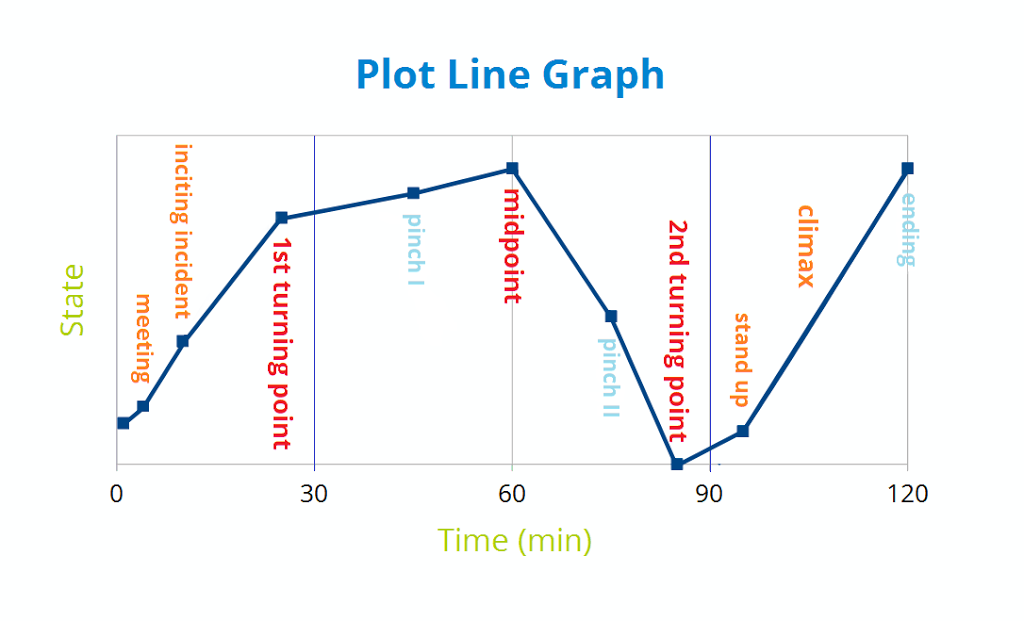

And there you have the beast itself, the three-act structure. I lifted this one off of Wikipedia because I decided early on that it’d be nice to have one with citations. Why would I care about citations for something so universal? That’s the beautiful part: people sometimes have disagreements over the exact shape of the three act structure. Though the overall basics are the same, the minor details can come and go depending on the opinion of whoever’s showing it to you. In fact, for all the versions I’ve run across over the years, there are only five elements of the three act structure that are actually universal.

The first universal point is that there is something called the inciting incident, a point where shit starts happening to our cast of characters. This can be something that shakes up the status quo or even just a minor event that sends people along their way. But inevitably the inciting incident leads to the first turning point, an event which hijacks your characters and takes them to parts unknown. From there, they eventually hit the midpoint, this place in the plot where stuff just starts going wrong rapidly around the middle of Act 2. When you eventually have it as low as it’s going to go, the low point, you’re ready for the second turning point, which is when the character rises from this low point to head into the climax. The climax is your big dramatic pull, the point where everything gets resolved one way or another.

So then how could anyone disagree about the structure? Those five points seem fairly obvious, don’t they? And yet, while you can find those five points I just mentioned on any outline given to you explaining screenwriting, the observant will notice that the picture I shared above actually has ten points labeled. Is that the real correct number? Nope, because another famous outline for writers comes out of Blake Snyder’s book “Save the Cat” (also a website devoted to the concept) which features a time specific outline for the structure of a film featuring… fifteen.

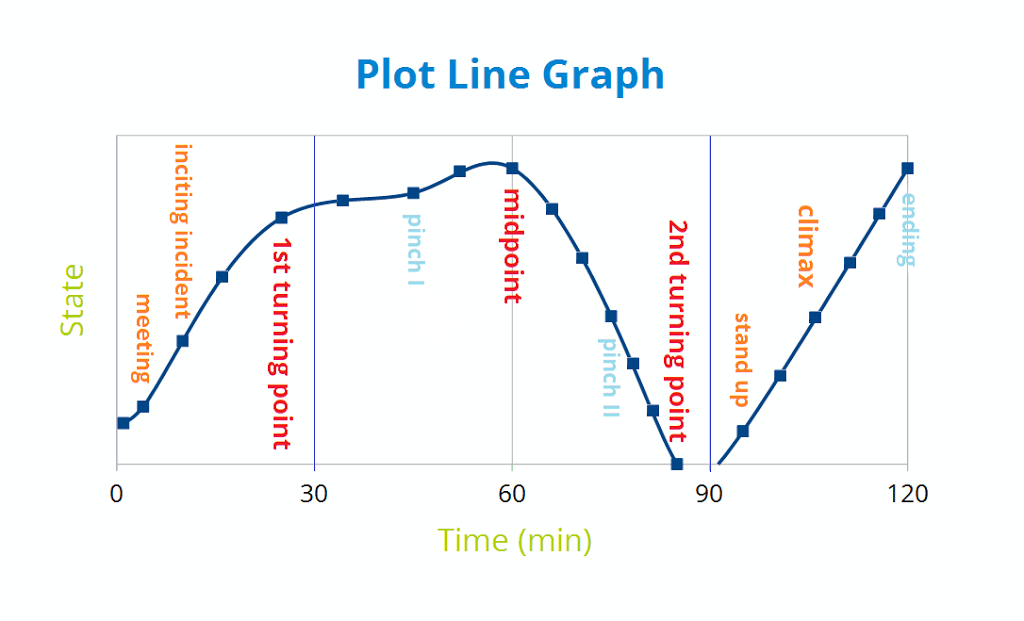

So how is it that all three of these things, which share commonalities but disagree on the specifics, can all exist side by side? The answer lies in the fact that none of these is really showing the real form of a film. Were you to really draw out the structure of a film, the picture above would actually look something more like this.

And there you see the beats.

In this context, beats are just events that move your story along. They’re the smallest named part of creative writing in this format and are fundamental to understanding the pacing of a film. While the three act structure may sometimes come with timestamps (as the two examples above have done), the real backbone of pacing in film comes from your beats. But that’s a bit harder to draw out, because if people were truly honest with themselves about the structure of screenwriting, it’d actually look less like the pictures above and more like this.

And this is because, despite the fact not many notice, there’s a lot more intuition in the process of film making than there is structure. In fact, film is actually a lot more like music than it is like other formats. Your beats set your tempo, too many beats, too fast, and your movie is just noise, too slow and it may just put your audience to sleep. The size and frequency of your beats helps guide your audience through the film and a well paced film featuring just the right number of beats will carry them from beginning to end so long as you stay within bounds of reason. In this way, they’re also a lot like chapters of a book, but with a greater limitation on the resources of time and patience.

It makes sense, when you think about it, that film ends up feeling so much like music. A song doesn’t start off in the full swing – it begins with something a little less complex that eases you into the music. But then, other instruments play or a change in tempo happens and you find yourself experiencing something else. The infamous example in the modern day is the guy who shares his dubstep with you and keeps saying something like, “wait for it.”

And then, BAM, something happens. For a dubstep song it becomes aggressive. For a story, they might’ve just found a dead body or have someone in their family kidnapped. But once that happens, you’re into the real meat of the music and the film.

And this keeps swelling and building until you hit that point where it is just in full swing and people are really feeling what you’re doing. It’s at this point that things might even go…too far.

And then, after you’ve got people drawn in, when they’re ready to follow you down to the bottom, you take them there. But you can’t stay there. You can’t rise once and then fall after that. Music is more complex than that, you have to take them through a few turns. So as you come down from it, it’s time to hit them again. You know, the climax after the low point.

And that’s the thing about pacing that a lot of people, especially new writers, don’t really understand. Pacing isn’t about specific numbers or timestamps. One outline for the three act structure is going to tell you that a movie should last about 120 minutes, another may say 110, but the truth is less specific than that. The truth is that pacing is about keeping your audience emotionally invested enough that they will follow you through the rises and falls of that arc you’re drawing. Your pacing is determined more by the quality of your beats than by their spacing. It’s like conducting an orchestra of emotion.

And when someone learns the three act structure and formulas first, but then fails to recognize the value of beats, something bad could happen. What can happen is that people see the points listed by formulas and structures and treat them like blueprints rather than guidelines for study. Sometimes people get so caught up in the formula that they don’t take time to feel the rhythm. And when that happens you’ve got a situation where the beats between these points become little more than transitions from one requirement to the next. That would look like this.

It looks fine, structurally. But the loss of those curves means that the work has lost a bit of the soul. When you have something like that, your pacing is never going to be right. Even if everything is spaced out perfectly, if your beats between the major plot points fall flat, you’re going to lose the audience. You have to make sure that you understand that every beat counts and the flow between these beats is the thing that’s keeping people in the seats. Done wrong, a bad beat can screw up everything you worked for. Done right…

It can be so smooth.

(I write stuff, like novels. Give them a read and feel my rhythm. Next time, I’ll hit on the thing that unites all story-telling and how you can use that to control your pacing.)