Pacing and structure, undeniably connected to each other. In the last few entries, born out of my inability to keep my head up long enough to do any research outside of what I already knew, I’ve discussed the structure of story telling to explain how it relates to pacing. When your structure is good, when your story is built right, the pacing takes care of itself. Someone who is entertained and invested in what you’re showing them will not complain about how fast or slow it’s gone, except the sometimes complimentary, “it ended too soon for me”.

But when I started this, I said that a lot of writers were learning things backwards. Certain more sophisticated structures have been taught as basics – essential and required. It leaves some people unable to adapt to situations that require them to change the way they normally work. If television requires you to write five acts but you’re only comfortable with three, it makes sense that you’d have some troubles adjusting. If you’re writing a novel having learned the three act structure, you may be handling your chapter structure incorrectly. Becoming too dependent on more sophisticated structures and formulas can be an issue that many new writers have to resolve over time.

But there are shared elements of structure and pacing that exist throughout storytelling. Just because the overarching formulas don’t always translate from one media to the next doesn’t mean that the fundamentals don’t exist. But the fundamentals often get muddied and buried by other forms. In fact, many people learn the true fundamentals second or third while others don’t learn them at all.

So today, as my final entry before I start digging back into Alternative Mythologies, I’m going to cover…

The True Essentials

The thing that has to be remembered about basics is that they aren’t blueprints. You don’t learn to build a house by taking the blueprints and then building the house right away. The basics of building a house start with figuring out how to work the tools and handle the building materials. Reading blueprints is a vital skill too, but if you don’t understand the materials going into the design you’ll quickly find that your house can still fall apart on you. In fact, the people in construction who understand the materials better than anyone are the ones who actually design the building.

So when we’re talking about essentials, we’re stripping away the formulas and the structures and talking instead about the things that are universal to the craft. There are elements that are a part of every formula, every structure and every basic guide to pacing. But despite these elements being so universal, they’re often an afterthought to the formulas or the guides. People write books, teach classes and create whole curriculums about the three act structure or pacing according to a formula. I’ve encountered it enough times to notice that it’s somewhat uncommon for a new writer to be aware of things like…

Logical Progression

I mentioned this term two entries ago and said that it had some parallels with the three act structure. The reason for that is simple, even the three act structure follows logical progression. But then again, so does the five act structure or the nature of chapters. You’ll find this in every storytelling format you can find and any of them that don’t follow it are either fantastic failures or considered some sort of art house experiment to see just how far you can take things.

|

| Though the fact you can re-edit this to chronological order shows it followed the rule too. |

But what exactly is logical progression?

Put simply, logical progression is the common sense idea that everything in your story has to make sense in the order it’s told in. This extends to every unit you could divide a story into. Every chapter has to make sense in relation to the chapters around it. Every act has to make sense in relation to the acts around it. Every beat has to make sense in relation to the beats around it.

I often explain it to people I’m helping as it being part of a flow. When your logical progression makes sense, it flows easier, everything is moving in the same direction. When your logical progression doesn’t make sense, you get blocked.

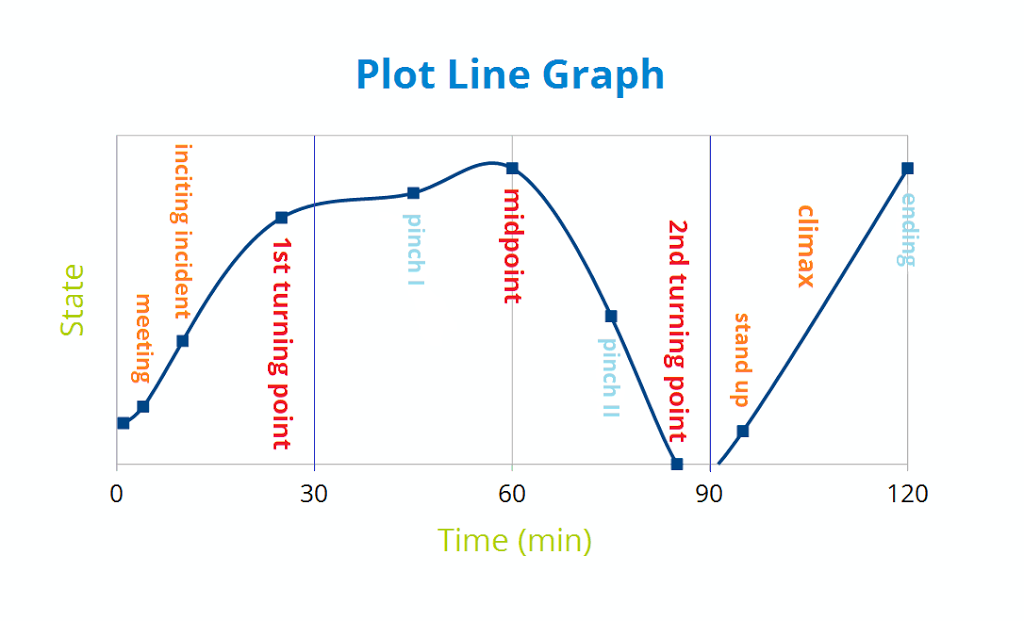

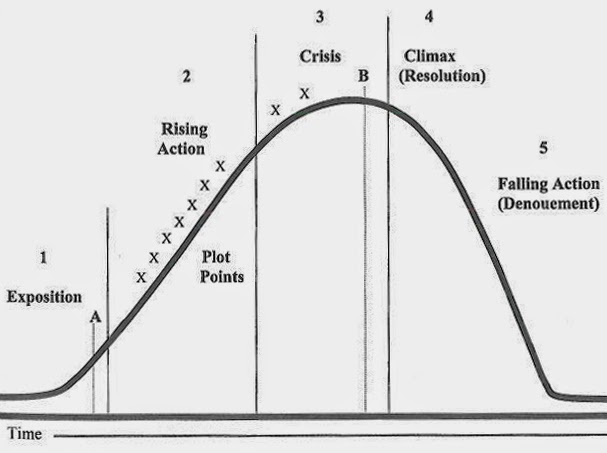

Maintaining logical progression is simple on the large scale – of course you want to have your ending after your middle and definitely after your beginning. But on the micro-scale it sometimes gets hazy. On the pictures of the three act structure that I showed last time you’ll notice that there are gentle curves everywhere rather than hard turns.

This is logical progression in play, every event along the line is flowing into the next one. Nothing’s just happening out of nowhere, it’s coming out of something that’s happened before (seen or unseen). And while you’ll only have a select few scenes marked on your outline, on closer inspection it could look a lot like this:

There are three key aspects of logical progression, questions that make sense and can be applied even when something isn’t entirely in line with one thing or the next.

1) Does it take the appropriate space?

The first element is whether or not it takes the right amount of focus. This is especially important to the overall idea of pacing. The element, whatever it may be, should never overstay its welcome. Use only as much time as you need to do it and don’t linger unless that pause itself serves a purpose. For instance, you may want to linger on something you want the audience to think about. You may want to linger on something that may have impacted people emotionally. You don’t want to linger on physical comedy.

|

| No matter what your opinion of the show. |

It may pay off once in a while, but after a time it just becomes annoying.

2) Does it progress the story?

This is another one resolved easily. If you can explain, either to yourself or someone else, how an element helps move your story forward – keep it. If you can’t explain it to yourself or to someone else then you should probably move it to another location or edit it out entirely.

3) Does this (scene/chapter/beat/act) make sense in relation to the (scenes/chapters/beats/acts) that precede and follow it?

This is self explanatory a lot of times. There are sometimes scenes that just do not belong where they are. The jarring feeling you have when something just feels completely out of place is instinctual for most. But if you don’t feel it, just consider whether or not it could have happened in the real world or in the world you’ve set up. Would people start telling jokes walking through a wasteland? Would a zombie enter through the window of your Victorian romance setting? Is Meatloaf there when he wasn’t before?

If so, why? If you can’t answer the question, it probably shouldn’t be there.

But that’s common sense, right? You’d think everyone that has ever written something would understand this basic concept. But sometimes it gets hazy just what does and doesn’t “flow” with the material around it. When is it okay to take a happy story into the dark places? When is it okay to take a sad story into a higher place? It can get confusing, especially since the traditional three act structure marks a specific “low point” when, as many of us know, an entire movie -can- feel like a low point in the right genre.

The truth is, so long as you fill these three requirements, the element should -fit-. But do not confuse “making sense” for “sharing the same tone”, because a second essential to all storytelling is…

Tonal Variance

A while back I read a ridiculous “reader-writer contract” which insisted on a rule that I could not abide by. According to that “contract”, the tone you set in the first few pages or minutes of your story is one that you have to maintain throughout. If you do not, you’ve violated some sort of trust. But even a cursory glance at the traditional three act structure shows that is not the case at all. Over the course of your story, there will be dramatic rises and falls.

But that’s the point. You see, one of the aspects of pacing and making sure that people don’t get bored is that you keep the tone moving over the course of your work. If you maintain one, prolonged tone for the entirety of your story, you’re going to lose people. Two hours of darkness can be exhausting if there isn’t a moment of satisfaction somewhere in the film. Two hours of nothing but slapstick can become annoying when you wish these people would just have a moment to give you a reason to care. Two hours of mindless explosions is a Michael Bay movie.

So you have to adjust your tone over the course of the plot. You may start off slowly and then build towards something more interesting, add a few twists and turns and maybe surprise someone by going down a darker road. The key part of this is to make sure that you follow the earlier essential of logical progression as you do – make your tone changes gradual and make sure they make sense. You have to make sure that the audience understands why your tone has changed and you have to ease them into it. It doesn’t have to take forever to do it, but a sudden sharp change can be jarring and feel too fast. You need to gradually move people through it.

Now, one of the things to realize, despite the fact that this is shown to you on the large scale in the average three act structure, the small scale still follows the same rules. I recently came to the realization that the Green Mile, due in part to having been a serialized novel originally, has a structure which can be argued to follow the three act structure but then include smaller three act structures in the side stories that occur.

In the middle of the film, during what could be argued by some to be the midpoint and into the second turning point, you can find the general shape of a three act structure despite taking place over only a few scenes.

It starts after the guards realize that John Coffey’s magic could be used to help the warden’s wife. After beginning the set up, the guards come to the decision to remove John from the prison and take him to the home, this turning point brings them from their status quo as guards to carrying out a small prison break. They take him to the home of the warden and his wife, building tension as everyone’s somewhat uneasy of bringing a convicted criminal to visit an ailing woman with a terminal illness. John’s abilities then put them all at ease, he allows the warden and his wife to communicate for the first time in ages at this smaller midpoint within the midpoint. And then, the turning point, John lifts the disease from the Warden’s wife, taking it within himself and curing her of her cancer… at the cost of his own health. The sudden decline becomes an issue, John may be dying from the destructive force he took from her body. And at the low point, when it seems John may die, he turns it around and punishes the wicked by sending the disease into the villains of the story. He has a miniature climax within the greater story.

And the thing about it is, the greater three acts of that movie do not have a traditional climax. Though people could stretch to try to make it fit, the truth of the matter is that the climax and the low point of the overall story are the same event. You see, John isn’t the protagonist of the overall story, the protagonist is Tom Hanks’ character Paul Edgecomb.

And here’s the thing about that which can leave the traditional picture of the three act structure somewhat unclear. You see, the climax is the point of greatest tension in the story, the place where something happens which brings the story to a resolution. This point normally follows the low point of the story where the character is as low as they can possibly be. But the thing about this story is, despite the fact John’s encounter with the warden has the low point (almost dying) and the climax (punishing the wicked) spaced as separate events, Paul’s story doesn’t.

You see, for Paul, the climax, the thing that brings this story towards its resolution, is the execution of John Coffey. Everything else in the story builds towards this point. The entire story is about how this man is eventually going to have to die even though no one wants to do it. And because no one wants to do it, that moment is also the lowest point in Paul’s life. Paul wants nothing more than to not have to order that switch to be thrown. But he can’t do anything about it, nothing of any value. So he’s forced to do something he hates doing at the point of the highest tension in the story.

And the thing is, unlike the normal three act structure where the resolution allows the characters to move beyond what happened – Paul can’t move beyond this. Paul gets no real resolution. Paul is haunted for the rest of his now incredibly long life by the fact he has killed something miraculous.

Normally ending on such a low note can be devastating to your story. But because there was still tonal variance leading up to this event, people ease into it. Not only that, but there is still a bitter sweet nature to this otherwise horrible moment in Paul’s life. And that bitter-sweet nature is brought to us by the last essential of story telling…

Emotional Variance

In the darkest moment of The Green Mile, there’s still opportunity for the soul crushing sadness to be broken for just a brief moment. You see, the overriding tone doesn’t change; it’s still a horribly sad moment (though, for an instant, you’re also angry at the understandably grieved mother in the room). But in the midst of it there are still chances for emotions to be orchestrated just a little bit more. It’s not the big things that can change the whole tone, it’s the little gestures.

One of the first of these is a slight turn away from the sad to the bitter sweet when John asks them not to place the hood over his head. It’s against policy to not do this, due to the fact the contortions of the face during the electrocution could frighten the people in attendance. And for any other prisoner, it may even be possible that they would ignore the request. But for John, the gentle man that’s won their admiration, they show this act of mercy to him. In this moment, you feel something beyond the darkness of the event and into the subtle shows of humanity that someone can have even in these darkest of times.

And a bit after that, Paul shows his admiration even more by stepping forward and taking John’s hand. In front of a room full of people who hate John for what they think he did, you witness Paul showing he loves him for what he know John did.

That’s the emotional variance, throwing in small nods that there is more than just the tone in that moment. The smallest of gestures that helps someone feel something other than the overriding emotion at play. Without this, without a well placed moment of feeling something other than what’s in that moment, there’s something missing. It may feel too big, too direct or even too cold. To put it another way, though we often groan about one liners in the middle of an action scene, that momentary laugh or groan allows us to process the intensity of the scene around it just a bit better. And a bitter-sweet moment like a handshake can punctuate just how sad the moment really is.

These breaks have to be small enough not to change the tone, but impactful enough to give us something other than the current situation. The tone flows in large, sweeping arcs, but the emotions can change from moment to moment, and should if you want to make your story feel well-paced. If you’re careful with them, they will make your overall story feel more natural to the audience. If you’re not careful, you can derail your tone.

To be honest, whole books could be written about things like this, whole books have. But, in the end, what’s important to know is that your story lives and dies on moments that flow into each other. Not all of them have to be large moments, they’re like seasoning on food. Too much, spoil the flavor, too little, there’s no flavor to be had. And they don’t have to be big things, they can be small things, small gestures. After all, the greatest lump in your throat in a sad story…

Can be brought by momentary acts of kindness.

(I write books. Maybe someday I’ll write a book to try to expand more on these concepts. But for now, I’ll stick to fiction… this was long and I didn’t cover nearly enough.)