As I write this, it’s May the Fourth, a day when people all over can come together for their love for Star Wars. It used to be a simple joke when people went around saying “May the 4th be with you”, but clearly that joke got out of hand a long time ago. We now see events based around it, people dress up like characters if they have the day off from work. And bloggers? We shoehorn in topics related to Star Wars for shits and giggles.

But not everyone understands the draw of Star Wars. On more than one occasion I’ve had discussions with people about whether or not the movies deserve the furious support that they get from clearly devoted, even zealous, fans. Why is it so pervasive, so lasting and so powerful as to make grown men giddy with excitement over Harrison Ford just saying the line “we’re home”?

And the thing is…you’d be hard pressed to put it into words why Star Wars is so loved. Anyone who even tried to debate the matter would find themselves running into road blocks along the way. The dialogue usually bounces from campy and dated to downright pretentious. The action scenes were usually pretty stilted and once they improved in the prequels we found more people angry that Yoda actually had the moves. And speaking of that, we can use the prequel trilogy to go ahead and say that special effects weren’t the magic bullet.

Eventually you fall back on the idea that the story was good and that the characters were original. But as I’ve pointed out before, George Lucas isn’t the best writer. More over, the characters aren’t really that original – mostly stemming from old archetypes that have existed since the dawn of human civilization. But that last point, right there, may just provide the clue.

You see, I hold that Star Wars is successful because, for all intents and purposes… we’ve seen it before…

Space Operas and the Monomyth

For a long time writers have been familiar with the concept of “the monomyth” or “the hero’s journey”, a concept proposed by Joseph Campbell in the 1940s when he recognized that a great deal of mythology to endure through time followed the same basic narrative over and over. The concept has since become ubiquitous in many fields of writing, particularly the fantasy genre which so closely mirrors the mythology Campbell was originally studying.

But as time went on, as with many forms of analysis, the concept started to become over-analyzed and blurred into other things. Campbell’s monomyth was specifically regarding the shared elements of legend, mythology and stories of magic and supernatural wonder. But given enough time and realizing that several of those elements were also present in other forms of storytelling, we eventually found ourselves at a point where some people would insist that the hero’s journey could apply to all forms of storytelling with some alterations in interpretation. In fact, in some schools of thought, due to some parallels in both structures, we find that people believe the monomyth and the three act structure are tied to each other and that following these will generally produce favorable results.

There’s just one problem: they’re not blueprints, and having them is not a requirement or a promise of a good story.

In the modern day, in fact, the monomyth’s connection to stories that become popular tends to waver. It is difficult to have a heroic journey in the Noir genre, for instance, as that genre tends to askew the concept of “heroes”. For that matter, it’s difficult to have a “hero’s journey” in a story about selfish actions. Few could argue that there was anything particularly heroic about the actions of the characters seen in stories of rampant nihilism like Fight Club. But even in modern stories where there are heroes, it can be a struggle to fit the monomyth when some heroes simply desire something of a more mundane nature – like a pair of shoes.

But it doesn’t stop people from trying. All too often, novice writers will take the monomyth and use it like a checklist for what they need to do to make their story work. Like the three act structure, this simple guideline for comparison and analysis can sometimes be misused and create a story that’s a bit… unnatural. But their efforts will continue and people will continue to teach these things because there is a profound truth in the analysis Campbell made. Despite the fact it’s not necessary to include the hero’s journey in a story in order to make it a good story – those that do and do so well tend to be memorable for generations to come.

And that, in turn, is what brings us back to Star Wars.

Sci-fi, despite originating as a derivative of fantasy in the first place, has long strayed from the concept of the monomyth. Given the hero’s journey focuses on the concept of a regular individual entering a more fantastic place, the framework doesn’t carry over well into a world where the supernatural in question is supposed to feel like a tangible part of the real world. Even in the softest of sci-fi, the conceit is that generally these fantastic elements of a world are meant to be part of the character’s mundane life more often than not. The work of Issac Asimov is a fairly dry read of things that could happen, exciting people because we are almost on the verge of it actually happening. The works of Philip K Dick are rooted heavily in a philosophy that mirrors the Noir genre of old, his most famous work being a cyberpunk Neo-Noir exploration of the nature of humanity. But that raises the question: what happens when you successfully apply the monomyth and all of its trappings to the sci-fi genre?

Simply put? You get Star Wars.

Star Wars wasn’t the first work in the “space opera” subgenre, it missed that honor by about 60 years, but the fact it is a space opera is one of the primary reasons it is so successful today. A product of the “Golden Age” of sci-fi, space opera is a ball of epic melodrama presented in the trappings of spaceships and blaster guns rather than dragons and wizards. But Star Wars was arguably the most true to the monomyth of any space opera to reach film by that point. While many before had featured bits and pieces as a result of doing their best to put the heroic spin on the alien rather than the supernatural, Star Wars hit almost every beat on the checklist (though not necessarily in the traditional order).

First of all you have Luke himself, a fairly boring character when you stop to take him out of context and really explore his earlier appearances. A regular, unsuspecting farm boy with dreams of being anywhere but the farm while still hesitant to strike it out on his own because of a reluctance to abandon his family. Luke is old enough to do whatever he chooses but still remains for the sake of his family. He’s not particularly compelling as a character, but he’s not meant to be. Through being the most mundane of the characters in the series, he is the perfect hero for the hero’s journey – reluctant, normal, incapable of fathoming the things he is about to behold but destined for more than he realizes.

And upon being forced from his comfortable little box he encounters a next key player in the monomyth, the supernatural aid, a mentor who is to show him a world beyond what he has known before. In the monomyth the mentor is usually an older person with seemingly unnatural powers, potentially a witch or a wizard, who steps in as a protective figure and becomes a mentor and guide to the unassuming and unprepared hero who has just stepped into a world they’re not ready for.

After encountering the mentor, it is time to cross the threshold, a moment when the hero has given up their previous reluctance and fully steps into the unknown, accepting their need to leave behind the familiar for more. Or, as Luke put it:

This then goes on to lead to fantastic adventures, with the hero fully accepting their role once they have entered the “belly of the whale”. To show you how accurate this is, I leave it for Campbell to describe:

“The idea that the passage of the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth is symbolized in the worldwide womb image of the belly of the whale. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died.”

And it doesn’t end there, other elements of the hero’s journey with a clear parallel in the original trilogy include:

The Road of Trials, where the hero is tested and begins their transformation from the person they were into the person they are meant to become. Often the hero is shown to fail one or more of these tests in a fashion that makes them doubt their path.

Meeting With The Goddess, a time in which the hero encounters someone who has embodied the sort of love that one would expect from their mother, the person who they will most love in their life.

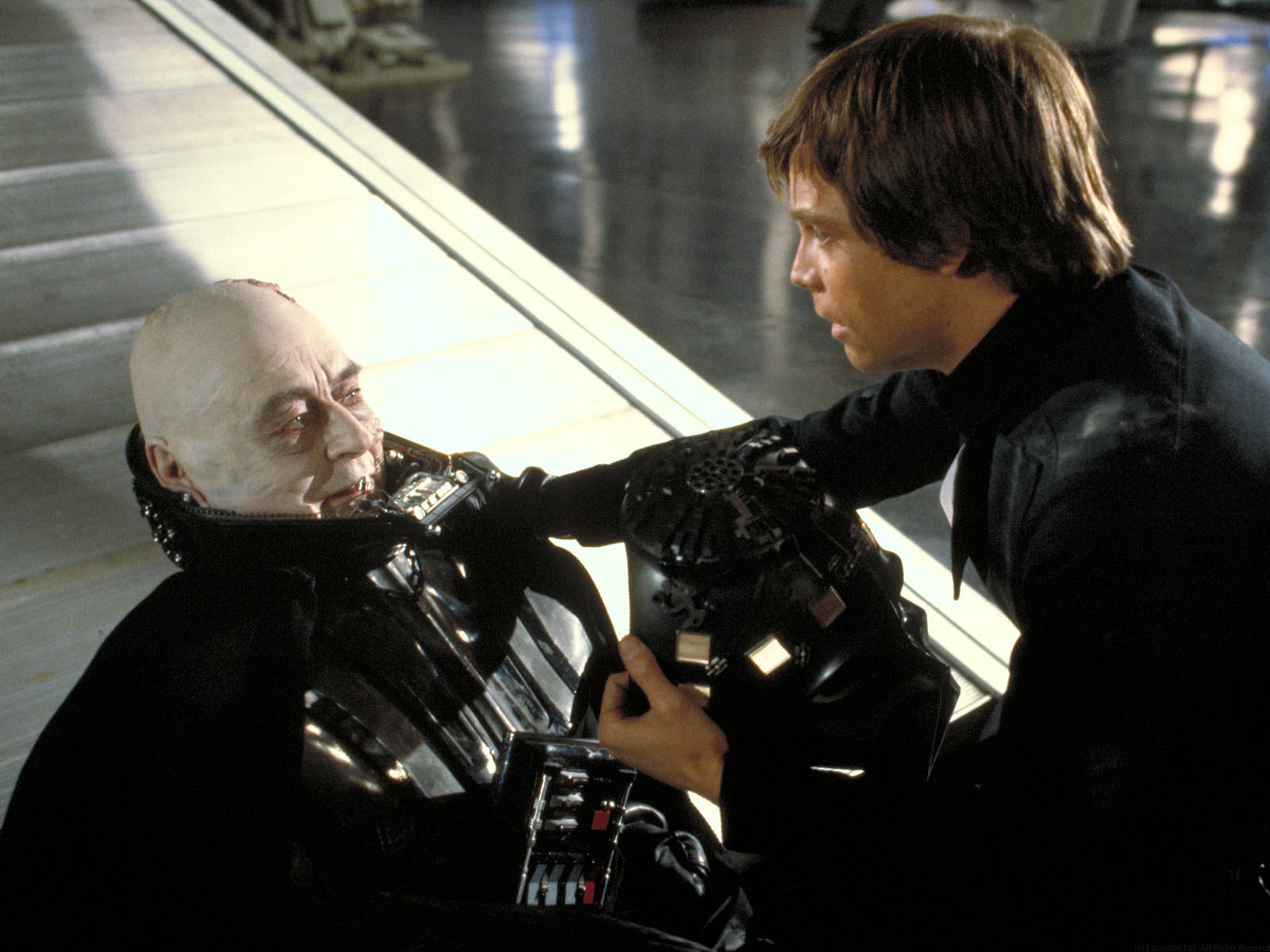

Atonement With The Father, which is…well… come on, this one should be obvious.

When accepting these similarities something becomes clear that makes it easier to understand just why Star Wars has found it’s place in our mindset. In the years since the story was splashed on the big screen, we’ve seen a lot of other stories with the monomyth in them described as being “like Star Wars”. Eragon was often described by some to be “Star Wars with dragons”, ignoring the fact it was following a lot of steps of the monomyth which had always been in fantasy. Guardians of the Galaxy has been called “the new Star Wars” by some because there’s a general familiar feeling to it. That familiar feeling may have something to do with the fact it’s about a normal guy being taken to an unnatural world due to circumstance and becoming a reluctant hero – experiencing his transformation into a hero while being inside the hulking remains of a giant creature.

In the end, when you’re honest with yourself and willing to see the flaws in the work, but also accept you still love it regardless, it’s clear that there’s something more to it that has managed to touch so many people. The truth is that people don’t love Star Wars for what makes it stand out, but because it’s a story that’s been engrained into the human psyche since before we even knew how to write it down. It’s a timeless story that’s been told time and again throughout history and Star Wars is the version we are most fond of today. It has already touched on two generations, starting to touch on a third, and one day many more to come. It is our culture’s addition to a long standing tradition, one we weren’t perfectly aware was being made.

Campbell’s book was originally called “The Hero of A Thousand Faces” because he could find this same story, this same character, in at least a thousand variations. For every major culture there was another version of this story out there, another face to be given to the hero who experienced these adventures. There will likely be more in the future, likely more being made as you read this very blog. And it’s fitting, maybe even necessary, that each new generation adds their own face to this figure in the monomyth. And all of these faces are still known to us, after all this time: Hercules, Gilgamesh, Buddha, Moses, Christ…

Skywalker.

(I write novels. I’m sorry to say they haven’t made a billion in merchandise sales like Star Wars, but I hope you won’t hold that against me. Follow my twitter to keep track of me, even yell at me if I’m slacking off, and may the 4th be with you.)