First created in the 1800s, originating with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the sci-fi genre is one of the babies of the literary field. Prior to this moment a lot of science and fantasy stories were considered one and the same since, at the time, science and magic were pretty much the same thing. Those were the days of alchemy and astrology that, while making progress, were deeply rooted in the ancient beliefs that had very little evidence backing them. The scientific method as we know it didn’t even really exist until the 17th and 18th centuries. So when Mary created a story around the idea of reviving the dead using chemicals and electricity (which…kind of came true centuries later), it was unprecedented for a reason.

And because of that, while sci-fi is about 200 years old now, it’s still evolving constantly. Science Fiction and Fantasy both became separate entities as magic and science started to drift apart from each other and establish their jurisdictions. Come the industrial revolution, not long after Shelley’s work, and the genre’s potentials became incredibly clear and led to an explosion of variety that she likely wouldn’t have seen coming. And, just as the “Golden Age” was about to begin in the early 20th century, something new came onto the scene.

Prior to the 1930s there was a genre known by some as the “horse opera”, a kind of melodramatic western story that entered the same sort of cheesy territory we now see in your daily Soap Operas. These were grand adventures and a tad overbearing in how earnest they were. Even for the turn of the century these were often considered campy. But then someone considered: what if you were to take those sorts of stories and put them in space?

And the space opera was born.

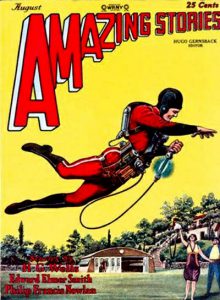

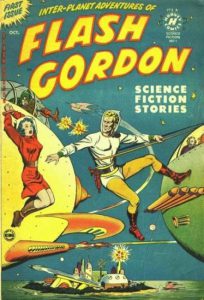

Though it’s arguable where in the genre itself really started, with early examples being cited in the late 1800s, it wasn’t really until the 1920s where melodramatic shit in space hit mainstream success and the genre really started to become a “genre”. Edgar Rice Buroughs probably had a lot to do with inspiring this, as his John Carpenter series was essentially Tarzan on Mars. But while he kicked off the popularity of such ideas he never really wrote a space opera himself, instead having stories that most would categorize as “planetary romances” (a subject for another day). But when a comic strip publisher wanted to get the rights to his stories they failed and needed to create their own. Hiring Alex Raymond to do it for them, what he came up with was one of the most enduring space operas of all time: Flash Gordon. It was cheesy, campy, and full of melodrama that surpassed the likes of even superhero comics (which were just getting started at the same time). But it sold… and it sold well.

Literary versions of the space opera genre found success as well with the likes of the Lensman series from E.E. Smith and the Foundation series from Isaac Asimov. And these stories began to form the language and visuals to be associated with the genre. All of them had the same sense of grandiose adventures in space, littered with space battles, interstellar politics and intrigue. And for decades the styles they established were what really defined “space operas” as people told stories of wars happening among the stars. But then, this all hit a tipping point when some guy got really lazy with his title and actually released a movie just called “Star Wars”.

The style hasn’t quite been the same since…

How Star Wars Left A Mark

Last week (as of this writing) was once again “May the 4th” and, while I wasn’t able to update the blog, I was left thinking about just what you could write on the subject. The thing was, what set in my mind most at that moment wasn’t Star Wars itself but rather the genre it was a part of. Though not the most influential story of Space Operas (that would still sit with Doc Smith’s Skylark of Space), it definitely put a marker on the history of Space Opera where things that came before Star Wars and things that came after were very different things. And when a Space Opera gets made today that doesn’t show those Star Wars influences, a lot of people would consider them “retro”, “nostalgic”, or “old school”.

In the time leading up to Star Wars the landscape was fairly different. Starting off as essentially a continuation of pulp novels and comics from the turn of the 20th century, Space Operas leading into the 70s were full of a general sense of adventure that made them fun but still lacked something that could reach mainstream audiences. But in the time since George Lucas left his mark it’s actually arguable that Space Operas, once a niche market all together, are actually a little easier to sell to mainstream audiences than any other kind of sci-fi. And a lot of that is because George Lucas made it a little more accessible to the average person by essentially reintroducing magic through inclusion of eastern philosophies and new age mysticism.

Having drawn heavily from the horse operas, naval adventures and chivalry stories of old, the Space Opera spent its early years heavily rooted in western ideas. This wasn’t an intentional thing, just a matter of writing what people knew, and for a long time the tropes held firm to this. The hero archetypes, while still following the monomyth, were generally idealized in the western sense in their backstories alone. John Carter, while not strictly a Space Opera, was a precursor to a genre and featured a man who exemplified the southern gentleman and soldier. Meanwhile Flash Gordon, who really kicked off the Space Opera genre in earnest, was an accomplished athlete and Yale graduate. In both of these figures their feats of strength and raw talent were what carried them through their adventures.

Meanwhile one of the most powerful creatures in Star Wars is about 2 feet tall.

This is in part due to the fact George Lucas loves whimsical stuff, and another part due to the era in which it was made. The 1970s were a time when a lot of people were beginning to see Eastern philosophy as an alternative to the religions and beliefs that their parents and grandparents had believed in. This led to many beginning to adopt or at least become aware of the sorts of stories found in the Buddhist and Hindu lore. Whether intentional or not, these things left a clear mark on Lucas as well.

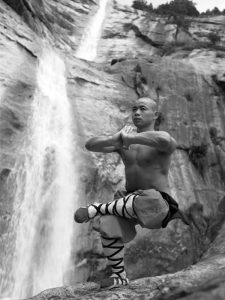

While many heroic tales of the west are focused in the acts of a hero’s feats of strength and courage winning the day, the stories of the east tend to focus heavily on the cunning and skill of their heroes instead. In the Eastern philosophy, a hero’s wisdom is often more important than their physical stature. And because of this, Lucas introduced the concept to Space Opera that the hero didn’t necessarily need to be the “All American” athlete or the archetypal hero role, but instead someone who gets beyond their flaws through finding a greater wisdom.

A further examination of the Jedi and their code shows this even clearer. The secret to a Jedi’s power is being able to control their emotions and purge themselves of wants and desires much as a Buddhist monk would. Where as they use the term Knight and are known to carry swords (albeit made of plasma), their actual code of conduct and physical feats mirror those of Shaolin monks more than monastic orders in Europe.

And the concept of The Force itself was also a more Eastern idea as well. Where as the Western philosophy has divinity as more of a conscious entity, Eastern philosophy often focuses on the idea that all things are connected through a life force. The focus of the monks that most closely resemble Jedi in our real world is to become one with the universe – a concept which is the pinnacle of Jedi training.

And while this isn’t the first time that all life in the galaxy was connected in Space Opera, it is the first time that it was influenced by Eastern philosophy rather than modern ideas. The Foundation series featured a concept where in the entire human race was to become unified as a single galaxy-wide intelligence due to the work of a robot for thousands of years. This united lifeform, upon completion, would be known as “Galaxia”. But unlike The Force, where all life is connected through an unseen natural energy, the idea of Galaxia was artificial from the start, an extension of Asimov’s belief that intelligence, particularly artificial intelligence, could continue to grow beyond its boundaries given time. Asimov loved to play with the idea that things could eventually become “too smart” and it was the logical extension of all of that. And that was the sort of grand schemes you would find in Space Operas prior to Lucas’ contributions.

Those kinds of grand schemes and the philosophy behind them still exist in Space Opera afterwards, but the inclusion of a different set of philosophies left a mark that is hard to deny. Not long after the success of Star Wars we saw the introduction of things like the original Battlestar Galactica, a show based heavily in a premise found at the foundations of new age mysticism – ancient astronauts and Atlantis.

At first these would seem unrelated, but the fact was that new age mysticism, while heavily influenced by eastern philosophies, also believed that there were greater influences in our distant past which got us to where we are today. Many believers frequently speak of the idea that Atlantis was the source of some of our great wisdom and that they got it from space faring sources. And Battlestar Galactica, hot off the success of Star Wars, ran with the idea and based a story entirely around the descendants of those ancient astronauts. Not long after, the idea of magic or near magic things being interwoven into these universes became fairly common place. It didn’t really matter if it made sense anymore, just that it felt like it made sense. And to help distract you, they would throw something else at you that wasn’t there before.

When you think of modern Space Operas, several elements are in the cultural mindset but the top of them has to be the fantastic battles. Generally, when you picture it today, you likely picture it with star fighters whipping around capital ships as they do their best to pepper these massive hulls with precision strikes while trying to avoid getting blasted out of the sky. It’s hard to imagine seeing these epic exchanges without those fighters in the middle of the fray… but before Star Wars you’d be hard pressed to find many examples of them.

The most successful Space Operas leading up to the late 70s were primarily focused on capital ships and few space battles involved anything smaller. Even outside of the conventional Space Opera genre you find Gene Roddenberry, an actual pilot before he became a writer, never introduced a star fighter into his work until around the 90s. Instead, Star Trek’s battles tend to be treated like naval warfare, particularly submarines, and no one ever really questioned it. The reason is fairly simple – fighter planes weren’t all that common when Space Operas first appeared and the concept rarely made sense to people until air superiority revealed itself to be the game changer we know it to be today.

But it also tied back into that concept of the eastern philosophy. Pilots don’t have to be the strongest, they don’t have to be the fastest, they just have to be the most skilled. Like the heroes of Asian lore, the most clever could be the most successful. And this also meant that a lot of times the underdog could be the center of the story. In the old Space Opera formula, it’s hard for an “underdog” to be able to overcome the odds when they’re dealing with giant warships. But this new philosophy, this idea of wisdom above brawn, precision over power, leads to opportunities where a smaller, weaker person can prove themselves to be just as capable as anyone else. And, when you really sit back to think of modern space operas…

That’s where some of the most memorable moments come from today.

(I write novels and write tweets. Though none of them are space operas, I do manage to be fairly melodramatic and a bit of a space cadet.)