Learning how to write is built largely on the idea of formulas. You’ll find many students and early writers follow these formulas almost religiously and sometimes, despite their best efforts, they never quite escape them. Time and time again you’ll find stories out there which could best be described as “formulaic” and it’s never intended as a compliment. Unfortunately, breaking away from it can be challenging because rarely do lesson plans include a guide on how to break the mold they so carefully made for you.

One of the examples of this is the idea of how the cast should be constructed. With certain roles being absolutely necessary to the idea of a story to tell, such as a protagonist, it’s easy to understand why. You wouldn’t want to go telling a story that has no protagonist or main character of any sort, as there has to be someone for the audience to relate to. You also wouldn’t want that character to have no one to interact with, because then there’s nothing to provide some of the texture the story arc would so badly need. But often there’s a sense that all roles mentioned in a typical formula are 100% necessary outside of the protagonist even when that isn’t necessarily true.

For instance, not every story requires an antagonist…

Adverse Reactions

Vital to the story in the same way that the protagonist is, the rival, villain, or antagonist is sometimes considered the most important support character in any story you may have. They’re generally responsible for driving the plot, even creating the reason for the plot, and will be the primary source of conflict in most circumstances. Some of the greatest stories ever told were practically defined by their villains, literally and figuratively. Lord of the Rings would have been pointless without a Sauron, Batman would be a silly man in a cape without a Joker, and every Disney movie needs at least one awesome villain song.

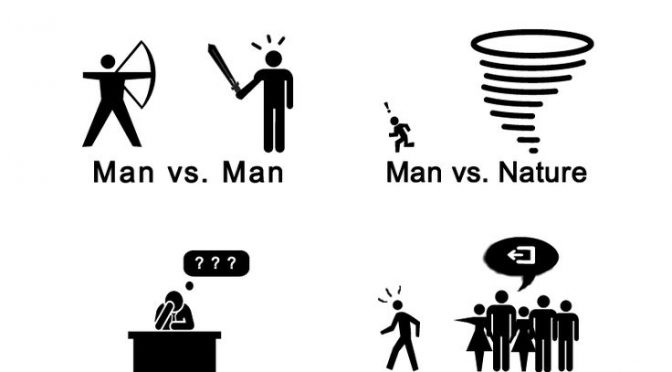

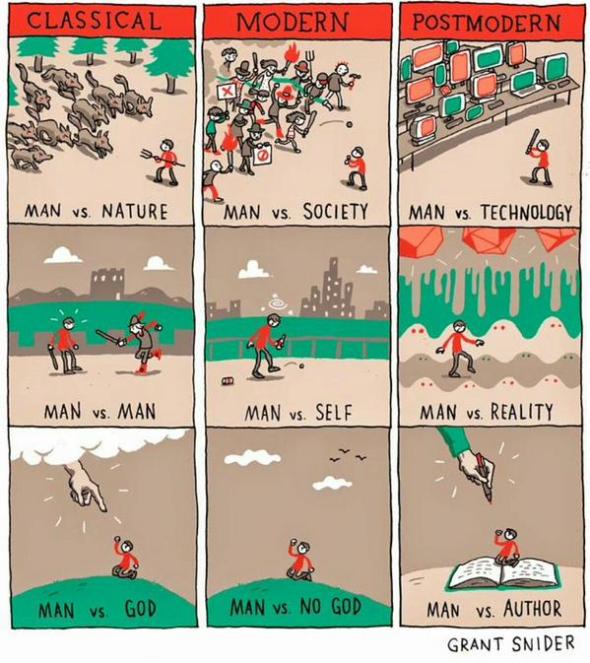

However, upon careful reflection you’ll notice that there are a lot of great stories where in a true “rival” is no where to be found. Though as important as the protagonist when they do exist, the fact remains that the universal element which stretches across all genres and forms of storytelling is not an “adversary” but rather “adversity”. Though something has to oppose your protagonist in some way, the idea that this opposition is always a living, breathing person is shallow at best. Some of the most compelling stories in our lives are those of people overcoming things that just can’t be embodied in a person – whether they be economic, social, or simply matters of survival. Yet, when you look around at various coursework they will, at times, insist that you must always have that obstacle embodied in a rival character.

But that couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact, one would go so far to say that, at times, putting a rival into a story that doesn’t require one would be forced at best and detrimental at worst. Imagine for a moment if there was a subplot in The Martian where it turned out Mark Watney was trapped on Mars intentionally by someone who wanted to kill him. Or, on the idea of roles played by Matt Damon, imagine if Good Will Hunting spent more time focusing on the douchebag in the bar rather than Will’s crushing emotional baggage. And, on the topic of castaways, imagine a version of Castaway where someone actively sabotaged efforts to save Tom Hanks – maybe it was that bastard Wilson.

The point is, while any of these stories could have worked (except perhaps that last one), they certainly wouldn’t have been the same stories that are known and loved today. These stories were about overcoming adversity, both internal and external, and a rival would have been a distraction from the story they were trying to tell. Any of these could have had such adversaries created to embody the adversity in the story, but then they would have ended up being like similar (sometimes lesser) stories. In the end, each of these demonstrates that the real source of conflict need not necessarily be a person, just an obstacle which pushes the protagonist and their supporting cast to confront something – be it their need for others, their will to survive, or their fear of being vulnerable.

Because of this I feel as though we shouldn’t teach people that every single story requires specifically a “rival”. I feel as though the real lesson is to ensure that you’re giving your characters a worthwhile obstacle to overcome, in one form or another. This can totally be embodied in a person, and I don’t want to live in a world without villains, but I don’t think that we need to teach people that every single story absolutely has to have an antagonist. I’ve encountered many lessons as of late which treat the antagonist as non-negotiable and I’ve known people who take these lessons to heart and struggle to break that habit later. It is, unfortunately, one of the causes of so many works being “formulaic” over time.

One of the ways you avoid being formulaic is to identify the actual basic elements you need and focusing on those rather than the derivatives generated for the formulas. An antagonist, while generally beneficial, is one of those “derivatives” in the end – a figure meant to act out the more basic requirement of adversity. And don’t get me wrong, there are definitely benefits to antagonists in terms of streamlining the process. However, while stories without an antagonist can be more difficult, and it’s generally helpful if the source of your conflict has their own motivations, there are still avenues where a story can work without that figure. After all, within our own lives, we rarely see a situation where all the problems we face can be placed on a single figure – generally it’s a whole tapestry of bullshit.

Some would argue that putting it in a singular character would in turn make for a sense of catharsis as a character is capable of receiving “comeuppance”. But there are other forms of catharsis to be had. One of my favorite films is Gattaca, and while it does have a rival in the form of Vincent’s brother Anton, the real catharsis of the film isn’t in Vincent overcoming his brother. Instead, for those who have seen it, you know that the real source of catharsis for that story is in Vincent managing to overcome the circumstances of his birth. And, in fact, Anton had little to do with the obstacles in Vincent’s path – he’s just there to represent the perfection Vincent never had.

The truth is, that’s more reflective of life than most scenarios we create in genre fiction. In fact, if you look at the more inspiring stories “based on true events”, you’ll find very few memorable “villains” or “rivals”. Another of my favorite films, Pursuit of Happyness, centers on the struggles of a person trying to get ahead and is prevented from that not by a single person but instead by a series of circumstances. Though there are certainly people who cause him strife, no one of them can really be declared the “antagonist” of the story. Our lives are full of challenges that can’t really be blamed on anyone and the same can be said for the people we look up to. The heroes in our lives, both the everyday heroes and those who inspire us for generations to come, are dealing with something far more intangible than another person.

As a result, while it certainly helps to have a villain in most situations, don’t let anyone tell you that a good story can’t be told without one. There are challenges that everyone can understand which don’t require a person to be the center of it all. And the joy that people feel in overcoming those sorts of challenges can be more visceral than the feeling you get from watching the bad guy lose. After all, one of the only things to ever feel better than watching a bad guy get what they deserve…

Is to see the good guy get it instead.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays. Find me on twitter and ensure I get what’s coming to me – whatever that may be.)