World building is a difficult task. Speculative fiction opens up so many possibilities that any other genre wouldn’t offer, but there are challenges that present themselves in the process of doing it. First you have to make your snowflake, forming a complex structure from multiple questions building on top of a base element. Then, as you build it, you have to figure out just how far you can really take it before the audience tunes out. You get both of these right, you should have a pretty solid world to give to people. This groundwork is something you need to figure out before you start writing, because after that point you’re going to find that trying to keep track of it all in the process of moving forward is going to be harder to do. You don’t build your ship as it’s on the water, that’s never going to work in your favor.

Once you get that all constructed, however, there are still some things you’re going to want to keep in mind. Even though the world itself might be everything you want it to be, making people see that world and giving it to them in a way they can process is still a tricky situation. Presentation is, in itself, part of how you make that world come to life for the people who don’t have the advantage of seeing it as clearly as you do. A lot of this comes down to simply writing well, but there are still some things which are unique to speculative fiction because of that challenge of building a world mostly from scratch. You have to find a way to feed them that world, a bit at a time, and make sure it produces exactly the effect you want.

How do you present your world to that audience? How do you make them see it the way you do without getting in your own way? That can take some practice…

Drawing Them In

That’s the real trick. In fact, by this point a lot of it really reflects the idea of a magic act. Every good magic trick starts with a great deal of preparation (the previous posts) to do what, in the end, is a fairly simple action. Sawing someone in half requires building props, getting an assistant, teaching that assistant what they need to do, and then practicing the timing so it all looks natural. In the preparation it looks like a really complicated act, but in action it’s probably one of the easiest stage tricks a magician could do (so much so that most of you already know how it works).

What really sets a good magician doing the trick apart from a bad one is how exactly they present that trick as they do it. Do they make you believe it? If they don’t, are they at least making you enjoy it? In the end, that’s really all that matters. We all know how that trick is done, but someone can still make it stand out for us if they can make it count.

But, obviously, you can’t use the same showmanship in the act of putting the fantastic to the page. You can’t distract them with a lovely assistant or flashing lights. There isn’t a trick to misdirect them and, even if there were, you wouldn’t want them to look away from the page. No, in the process of trying to present a fantastic world in text, the trick is to actually be more subtle about it. You want them to be jarred less often, to not really be left focusing on your swerves from the normal. You want them to feel like your swerves are the normal. These things will still be every bit as fantastic as they were before, but the audience will feel like it’s natural, and that’s what you want most.

And that starts with…

Pacing

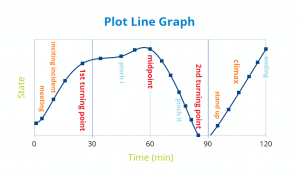

One of the biggest issues with world building and presenting it is making sure that you’re getting it across with the right balance of clarity and discovery. You don’t want to show too much of your hand too early, releasing your biggest tricks early on in the show, but you also don’t want to shroud it all in mystery. You need to make sure that when you do reveal something, it is revealed in the clearest fashion possible and that you choose the right moments to do it.

There’s a natural inclination for most new writers to move in one of two directions from the start. Some writers, worried the story isn’t interesting without some of the gimmick and novelty of the world they’ve built, will keep the fantastic elements close to the chest. They’ll hold onto these wonders as tightly as possible, keeping them like secrets and not giving any room for the reader to actually get pulled into the world they’ve made. It seems counter-intuitive to put so much effort into building a fictional world only to try to hold it back as much as possible, but nerves are a hell of a thing. All too often, people who are doing this are holding onto what are simply fascinating details as if they were dramatic plot twists. You find in this sort of presentation that the audience will become impatient with it, expecting more to come but then not getting it soon enough to make it worth their while.

Others, wanting to make sure that people understand right away that the world is strange, will give away their biggest secrets earlier in the story than they should in a rush to make people know exactly what they’re in for. In their need to make sure that they aren’t somehow deceiving or underselling the audience, they’ll give away all of the interesting bits early on and remove some of the magic from later in the story. This sort of top-heavy presentation tends to result in an uneven feeling, jarring as all of this information comes rushing their way and then being left confused as it seems like the rest of the story is mundane as can be.

The answer to both of these is to make sure that you order your world’s details by what I’m going to call the three i’s: importance, impact, and impression. Important details are the ones your world just wouldn’t function without. If your entire world is hinged on the premise of things happening in space, you should probably start with something letting you know that you’re in space. Case in point, first shot of Star Wars was the underbelly of two Starships…at war.

Impact is when a detail you happen to be revealing will somehow swerve the story’s direction because they’ve come to the scene. If your protagonist happens to be part of a long bloodline of warrior monks, for instance, destined to overthrow an evil emperor – that detail has impact. You’re going to hold onto those a bit longer, making sure that they’re revealed to the world when they become important to the plot. You can foreshadow these for a while, maybe make parts of it known a little at a time, but reveal the complete detail when it will make the most impact on the story at hand. For instance, this particular warrior monk destined for greatness didn’t learn the full truth of his lineage right away.

And, finally, those details which aren’t really important or make a lot of impact, but still leave an impression. These details just generate a little bit of flavor and help flesh out the world for people in subtle ways as you go along. The kind of music your fantasy creatures listen to, the clothing they’re going to wear, the kind of hobbies they enjoy – these have almost no value to the story, but they build the world none the less. These things can go anywhere and make the story better in the process.

But another pitfall of pacing can happen in speculative fiction even if you parse it out correctly, the infamous…

Info Dump

The info dump is a bit of a dirty word and tends to happen a lot in speculative fiction, especially earlier works. The details that shape our worlds can be pretty complicated in our heads. We know so much more about them than our audience does and there’s an instinct sometimes that giving only a fragment of that information is going to do the detail a disservice. Before you know it, you have otherwise solid writers wasting paragraphs on details that no one really needs to know.

Most places out there will tell you that you should never go into detail about something complicated in your world, but that’s unreasonable. You can’t simply drop a word on people and expect them to know what that word means without some explanation. The issue comes in finding the place where the information you’re sharing has crossed from informative to distracting. For instance, it’s okay when someone describes Mithril as “true silver”, “one of the strongest metals”, and so on. People need to know what it is and why it happens to be worth mentioning. If you just happen to drop the word without explaining it, people are going to scratch their heads.

On the other hand, they don’t need to know the full backstory of the material. They don’t need to know exactly where it’s found or crafted, unless it happens to give weight to the creation. You don’t need to know the age of it, unless that age connects it to something else. You don’t need to go into detail about the person who crafted the object itself, unless that person has value to the world beyond that creation. In essence, share the details that are important as they’re important, and leave the rest for another time.

And, while on the topic of odd words that need explanation, one of the last things you really need to be careful of when making your presentation is…

Word Choice

The words you use at any time can change the impression of what you’re saying. Someone who jogs will seem less energetic than someone who sprints – they’re both a form of running, but we have a pretty good impression that one is more urgent than the other. So making sure you’re using diverse, unique, and energetic words to make your writing more dynamic is essential. However, a lot of speculative fiction writers tend to take this a bit too far.

There’s a tendency for speculative fiction writers to spend a lot of time on using words that are a little too unique at any given moment. One example that I saw recently was a short story that insisted on underscoring every action and description with as many mechanical or technical sounding terms as possible. Rather than eyes, the characters had “optics”. Rather than ears, the characters had “auditory sensors”. Mentions of servos, gyros, and circuits abound in this sort of writing and most of it is hard to get through.

It’s not that the audience isn’t capable of it, but when you’re trying to make the language unique – you usually succeed. This is both a bonus when done well and a horrible distraction every other time. Unique language is harder language, by default, and requires more effort for a reader to go through. They may understand everything that you just said, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it felt natural to them as they figure it out. If a more common alternative for the thing you’re describing exists, you should use that alternative. It’s okay to describe your robots “blinking” their “eyes” because that’s how most people would describe it themselves.

A great rule of thumb is to make up words to fill in gaps and use the stranger language only in dialogue. It’s not that you should never use colorful language. Just make sure that when you use the language it’s in the right place. Because these colorful flares, combined with the offbeat details, and the right timing…

Can put a great spin on otherwise common tricks.

(I write novels and have a twitter account. Read both!)