Not long ago, James Patterson received the Innovator’s Award from the LA Times. This award, now in its 36th year, is one given to those with innovative business models or uses of technology to further the narrative arts. Essentially it’s given to people who happen to come up with a new idea that makes an impact on the literary world. And while I don’t know the exact reason the award was given to him this year, I can probably guess it’s because he’s the most successful author in the world… that doesn’t write books.

And for those of you who follow this blog regularly, you shouldn’t be surprised by my taking that jab at him. For some time the joke has been that I treat Patterson as if he was “he who should not be named” – taking a quick jab in his direction, refusing to name him, but posting his photo so you know what I mean.

I know I’m not alone, I know a lot of people have criticized him for the same reasons that bug me. Normally I would just move on with my life after making that kind of comment so I can go on doing my thing. But a recent rumor (that I won’t be spreading today) got me thinking about Patterson and realizing something I hadn’t before:

I don’t dislike James Patterson or his brand – I dislike what it means about our industry…

Ghost Of A Chance

James Patterson, as a person, is supposedly a great guy. He’s a philanthropist, he takes care of his community, provides helpful advice to new writers, and he encourages kids to read. He wants to reach wider audiences and is deeply concerned for the future of reading in our country and the state of our libraries. So as a guy who supports the arts, I will give him credit for that and I haven’t seen anything about him as a person that I would necessarily have a problem with. But as a brand?

That part’s a blight on the industry.

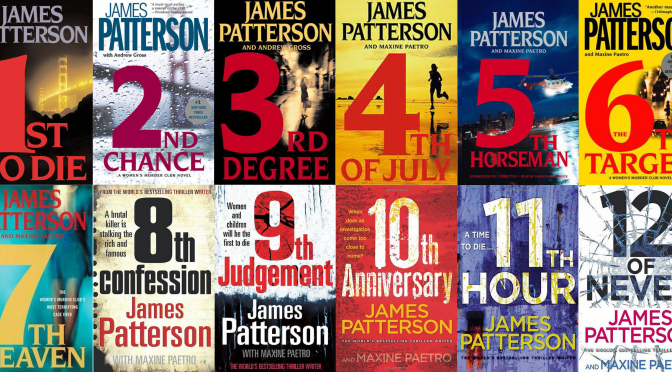

Because in the 20 years that James Patterson has been an author full time, he’s spent at least 14 of those using “co-authors” and doing so blatantly. He doesn’t hide it, he doesn’t even try to, and relies on it so heavily that he’s “publishing” 16 books this year alone. Everyone in the writing world knows it, but most of his fans wouldn’t really take the time to notice. After all, who spends their time watching release schedules for books they don’t want to read? And most people who buy his books don’t realize he wasn’t the one who wrote the damn thing. I know because I didn’t when I first got one of his books.

Years ago, before I lost my mind and decided to be a writer, I was part of a book of the month club. It was a simple discount book club where you would join up and get discounts on any books you want so long as you bought a certain number of them within a year. They would send you e-mails with their newest arrivals and would automatically send those to you if you didn’t opt out for you to take a look at and potentially keep. And during the time I was signed up with them I happened to receive a James Patterson novel and, not knowing what I do now, decided I would keep that one to read another day. It wasn’t until years later that I happened to notice his name wasn’t the only one on the cover.

It was never advertised as being co-authored in their e-mails, and few of his books generally are. For people within the writing world it’s well known what Patterson does, but to the laymen who just happens to buy the book or get it sent to them it’s almost invisible. Patterson is the only name that they ever really notice and is the only face you ever see on those goofy commercials where he tries to pretend he isn’t just a marketing machine. From 2002 to 2014, Patterson had two dozen co-authors and had only written 20% of his novels alone. This would still be impressive if those numbers were recent, what with him releasing 15 books a year for the last few years, but these numbers come from before 15 books became his standard. As of now, that 20% is probably lower and I’m scared to look for myself.

And it’s nothing about the collaborations, I’m all for people working together on a project if they’re actually working together. Just recently The Expanse turned out to be a fantastic success and took off with a bang after being written by two friends writing under a single pen-name. But those guys happened to work on it together and had put a great deal of time on the work as a team. That’s not what Patterson does, Patterson uses ghost writers, shamelessly, and with great bravado.

Often, in his advice to beginning authors, Patterson gives two pieces of advice almost universally. First, always have an outline so you know where you’re going. Second, keep your chapters incredibly short – that way you “keep the readers’ attention”. But when you look at his books themselves, something else occurs to why these pieces of advice are so important to him. Because, you see, I noticed something when I finally cracked open my one James Patterson book: chapters in his “co-authored” books are about 2 to 3 pages long. Essentially, each new bullet point on James Patterson’s outline is a new chapter that his “co-author” writes and rewrites until they get his approval. He’s even openly admitted this is his process.

Some would say that if it’s working it was the right thing to do. But the fact of the matter is that Wall Street disproved that concept years ago. You can do something that makes you a lot of money and still happens to be damaging to the thing you love. For every time James Patterson does it and gets away with it he reinforces the problems that may very well kill the art-form he’s trying to promote in his other endeavors.

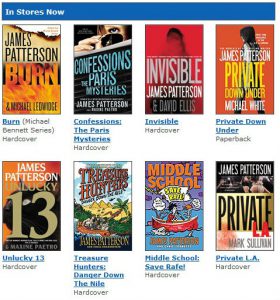

As the publishing industry continues to struggle, it finds that the root of most problems is due mostly to stagnation. Recent efforts have started to get books to rally back, and in all of these cases it was due to getting fresh blood into the system. But the traditional publishing industry, by and large, is still driven primarily by two forces; trends and name recognition. And the thing to remember about both of these things is that they are painfully finite. Trends are fleeting, that’s the nature of the beast, but name recognition has a literal issue of mortality attached to them. I hate to say it, but James Patterson’s characters will certainly outlive the man himself and name recognition….

That clearly favors the big dog in the relationship. In fact, the “Women’s Murder Club” series, pictured above, actually changed authors in the middle of the series. The idea that you wouldn’t be expected to notice, or even care, is part of how the scheme works.

So what you have with his practices is a situation where his name is more important than the work and his style is more important than who he works with. There are two types of James Patterson co-author, one who is successful already and is doing it for the experience, and one who is struggling and needs the opportunity. For the first group this is just a chance to do something interesting, a chance to work with someone who is clearly the most successful American author in the last decade. For the second group, this is a paycheck and an opportunity to get noticed that they may desperately need when he shows up. Some would argue that these are enough and that the second group will almost certainly get an instant best-seller and opportunities at book deals of their own, but that leaves the question: what are they getting those book deals to do?

Those people who write for James Patterson don’t become known for their own work, they become known for mimicking his work. They’re controlled by him from above, guided into mirroring his style, and he even brags that these people “learn a lot” while working under him. So yes, they’re given book deals after their best sellers, but those book deals are asking for more of what was in that best seller – they’re being asked for more James Patterson books. These people go from writing James Patterson novels to being given deals to write reheated James Patterson stories for a decent part of their career. They’re going to make money, but they’re not going to escape his shadow for some time. It doesn’t help expand the industry and takes people who may be gifted and stifles them for years.

And that’s the thing, for each person involved it may be a good deal. You get paid to work for a legendary author and you demonstrate that you can tell stories like him. You may even have fan bases who follow specifically your series under him. But after this, you’re still speaking in his voice, the industry is deprived of new voices, and the industry continues to reward his name rather than your efforts. They keep putting money behind a brand rather than new talent, and they continue to chase the same old traps that got them into the precarious position the industry has been in for the last decade. And they’re validated by the fact he can publish and market more books per year than months on the calendar.

And when he dies, which will someday happen, we’re left with a hole where the number one best seller in the industry used to be. The people who wrote under him won’t necessarily fill that gap, and the publishing industry may go ahead and do what they’ve been doing all along – attaching his name to the works of others. Before you know it, James Patterson becomes like Tupac and releases new books long after his death. One day they may even shoot those stupid commercials using a CG recreation of him to sell the book. And all the while…

He’ll still be hiding the other name on that cover (maybe even set your name on fire).

(I write novels. Someday I’d like to write a best-seller, but if I go down in flames they’re going to be honest flames. Meanwhile, if you want to burn me, feel free to do it on twitter.)