Your audience’s expectations are a strange balancing act. People like the familiar, they cling to the well worn and comfortable, but they can just as easily reject something as being unoriginal. We’re hard wired to want something that we recognize but at the same time demand something new, meaning that we’re often put off by things that are either too familiar or too unfamiliar. And, generally, we go into everything that we read, watch, or play with some expectation of what we’re going to get and what we want from it.

You’re under no obligation to meet all of these expectations, of course, because it’s impossible to hit every single expectation thrust upon you. But, as I mentioned not too long ago, you shouldn’t just brush off those expectations either. If you prep someone to expect a payoff, you owe a payoff, and using someone’s expectations without intending to include a payoff is eventually going to backfire. So clearly there are two completely different kinds of expectations – those that work for you and those that work against you.

The question is: how do you figure out which are which?

Tropes, Cliches, and Subversions

Though it’s common for people to seek originality, as I just said, it’s rare that they want something too original. The avante garde approach to creative work is as niche as you can possibly get and generally puts off more people than it draws in. You could go into something with full intention of absolute originality, but the fact remains that only a select few will find something of interest in it. And, because of that, there are going to be elements that you can always expect to appear from one story to the next, particularly within the same genre. These, of course, are what we know of as tropes.

The trope is an incredibly useful but somewhat dangerous aspect of fiction – particularly what we would call genre fiction. Essentially acting like the narrative equivalent of lego blocks, tropes can be assembled together in any variety of ways and help you create something original even if the constituent parts have been found in other places. We as writers don’t necessarily even intend to use them, they just kind of manifest as we work. We’ve been exposed to the same sorts of stories and information for so long that a lot of us have similar thought processes and they tend to take shape in these tropes. Sometimes, we might be aware of them and eagerly make use of them, particularly if they are an old favorite of ours or if we think we have an original take on it. But, generally, it’s just something that kind of happens and, while we tend to dread them, there’s really nothing wrong with using tropes in and of themselves. Hell, generally a properly utilized trope is going to be a strong point for fans of your genre even if they’re a point of criticism for people outside of that fanbase.

But the question really becomes: when does an element go from being a trope to being a cliche?

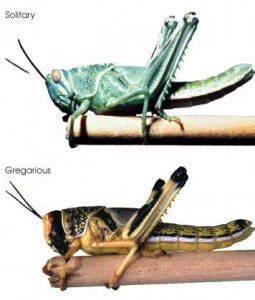

People often debate about what difference, if any, there is between tropes and cliches. In a very basic sense they’re the same thing: plot elements which are repeated over the course of many stories to the point at which the audience is familiar with the repetition. Some tropes are so common there are entire websites devoted to pointing them out and identifying when they’re used well and when they’re just kind of silly. But the fact remains that we feel there’s a difference even if we can’t pinpoint what that difference happens to be. The rule of thumb in most communities that a trope is a trope until it becomes unwelcome and that unwelcome tropes happen to be cliches. Fundamentally, like the grasshopper and the locust, tropes and cliches are two names for creatures which share DNA but produce dramatically different effects on their environment.

To encounter a well used trope in a work is like meeting with an old friend or family member, they make you feel comfortable and it’s a little like going home. You may laugh at it being there or point it out after the fact, but it still feels like a positive element even if it’s a little obvious. On the other hand, the cliche is like meeting with your ex – there’s a damn good chance you never wanted to see it again and it makes you a little angry it’s even there. We tend to have a hard time putting our finger on why, but something about that trope just mutated into something we hate. And, despite the fact we single it out when we make our criticisms, I don’t think it’s the event itself that makes a trope into a cliche but rather the things immediately around it.

Though many people often accept that a trope becomes a cliche when it’s been used too often, that’s not entirely true. There are certain tropes that have been used so long that we almost consider them requirements. The Hero’s Journey, considered an essential first step to learning how to tell a narrative, is a series of tropes that we don’t just accept but actually teach to each other. Despite having existed ostensibly since the beginning of language, The Hero’s Journey is still treated with that warm, familiar feeling rather than scorn. And those tropes are so prominent that they can even be found in stories retroactively and whole classes are devoted to identifying these elements in other stories in order to teach writers how to properly use them. Yet, despite being so prevalent, we only consider it a negative thing if used improperly – so clearly it’s not a matter of simply being overused.

The fact is, tropes become cliches not from frequency of use but instead from how they’ve been presented. If you can see the trope coming or you can see what’s going to happen next because the trope has appeared, the story has stepped out of simply familiar and into being predictable. However, predictability in and of itself isn’t enough to turn a trope into a cliche, it also has to become something worse: mundane. As I said before, expectations require pay offs. If the pay off is satisfying then even a predictable outcome can be satisfying. But if the pay off is simply run of the mill, then you run the risk that it’s boring instead. And, if that predictable outcome is boring, you’ve got yourself a cliche.

So this comes back around to figuring out which expectations you meet and which ones you subvert. If you step back and really assess the course of your tropes are taking, you should be able to get a pretty good idea of which expectations are working for you and which expectations are working against you. A good trope should have a feeling of catharsis from being there, it should feel like you’ve properly built the audience to this moment and that they’re going to want that result to happen. A properly built romance will result in a kiss, a properly built conflict may end in a fight, and a properly established mystery will result in a satisfying answer. However, if the beats leading up to and out of your trope are kind of a straight line that don’t really build up to anything but just kind of happen because they’re supposed to, you might be in dangerous waters and it may be worth subverting that trope. Because a good subversion of an unwanted expectation is just as cathartic as meeting with a positive expectations.

Now that’s not to say that making these judgments is particularly easy. Even identifying which ones are predictable can take some practice and figuring out which of those happen to be mundane is even harder. In fact, despite your best efforts, you’re not going to subvert all of your cliches. But even the effort to do so can go a long way towards leaving a mark on your audience. Done well, a series of good tropes and a couple good subversions will make your audience feel like you met every expectation even if you purposefully dodged a few. It’s just a sad truth that even after all of that, you won’t catch everything and some of your subversions may not hit with everyone. Fortunately, no one’s perfect and those mistakes will be made by everyone – including major successes.

One of the biggest examples of subverted expectations I saw in recent years was Marvel’s Thor: Ragnarok. Though you could find other successful examples of subverted tropes in the likes of Game of Thrones (which deftly destroys any idea of a hero bubble), many of these other examples just subverted one major trope and still did their best to meet other expectations. You expect to see those dragons eventually, damn it, and when you do you’re going to enjoy them. But in the case of Thor: Ragnarok it was like the creators took the rulebook established by the previous two films and threw it out the window.

Most of the time this worked incredibly well. After two films of meeting the expectations of other kinds of tropes, the sudden flip to a different atmosphere with almost completely different genre trappings made the franchise feel revitalized to many. However, despite overwhelming praise, there were still some mixed results in there. Some felt that the subversions went too far. While no one was particularly against the idea of having more fun with the characters or with going on fun space adventures, there were points where the creators seemed to be too invested in subversion. And, while the majority of critics and a large portion of the audience were willing to overlook these moments, there were still some who felt like they had been robbed of that previously mentioned catharsis in some of the most important moments.

One moment in particular is near the end of the film as all of the major battles are going on and things are reaching their climax. Bruce Banner, the Incredible Hulk, sees a need to become the Hulk despite the fact there’s a chance he may never be able to return again. To some, this moment had a weight to it, an expectation of not only an epic scene but a heroic sacrifice as Bruce may very well be sacrificing his very identity. Accepting his possible fate and deciding to put the needs of others ahead of himself, Bruce stands up, says a few final words, and takes the leap…

And, as funny as it might have been to a lot of people, I’ve known more than a couple who wished for the catharsis instead.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays. If you want to know what to expect of me, I recommend you follow me on twitter.)