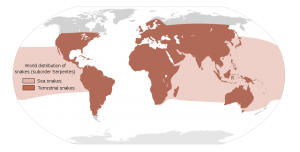

So far, my tour of world mythologies has been mostly about showing everyone a glimpse of the world outside of our typical fantasy genre offerings. And along the way it’s easy to notice similarities that abound. People try to explain the animals they encounter in the wilderness, they try to explain the weather, they share a fear of death or of the idea that the dead may remain. Some of them may combine aspects to become things such as a rainbow which is really a massive serpent, or a cobra which holds the earth aloft. Come to think of it, a lot of mythologies involve the general idea of “snakes”.

But the similarities make sense: our cultures have intermingled at one time or another throughout history. We not only respond to the world that we know, but the world others have known. Shared fears and shared concepts bleed across borders and vast distances. And, as I spoke of last time, at least one culture is so intermixed with every other culture around them that we hardly know them while still knowing almost everything about them. The Amazigh are, for all intents and purposes, the Beatles of Mediterranean mythology.

But what happens when you take a culture and stick it in a place where there’s nothing to really interact with. Put people on a set of small, tropical islands off the west coast of Africa, away from the empires and constant movements of the Mediterranean seas, and what do you get? Well, you get people who have the most distilled essence of what mythology looks like when there is no need to explain the gods of other people. You get a people who have no Mongols, Hippos or invading drunken barbarians to worry about. In fact, while it remains true that a major driving force behind mythology is what scares or confuses people, only one thing has ever really scared or confused the aboriginal natives of the Canary Islands:

A fucking volcano.

So, of course, the only real story I have from the mythology of the Guanches of Canary Islands is one explaining eruptions. It’ll do.

Guayota: Not Fucking Around

Once there was only the sky, Achamán, who was the creator of all things in the world and father to all living beings. He crated the waters of the ocean and the land that the people lived on, brought fire to the world and filled the air. He sat aloft in the heavens, overlooking his creation and bringing them rain as they needed and clear weather when they did not.

And in the domain of Achamán’s creation there were many supernatural beings who lived alongside the people. These entities were known as the Maxios, nature spirits who were embodiments of the natural world and spirits which could commune with the people, acting as messengers between the mortal realm and the realm of the gods. They would often be found wandering the hillsides, drifting down along the slopes so they could receive the prayer of the people and translate them to the heavens.

The gods who would receive this worship lived in these mountains, gateways to the other world, where they would emerge from time to time and descend once again when the time came. One of the chief of these gods was the sun herself, Magec, who would also be known as Chaxiraxi, the sun mother. Magec brought the people warmth and light throughout the day, rising from the horizon in the morning and setting behind the horizon again at night. As she did, she would sometimes transform and become Achuguayo, the moon, a male deity who would continue to shine down light on the people at night so they could see through the darkness.

But while the Maxios and the gods lived in harmony with the people, not everything in Achamán’s domain did. Beneath one mountain in particular, Mount Teide, there was an evil demonic force known as Guayota, the king of darkness and the underworld, leader of the Tibicenas, woolly dog-like beasts of fire and smoke. Guayota and his followers were destructive and malicious towards the world of the living and the other gods. At night, under the cover of darkness, the Tibicenas were known to wander the land of the living and take people and their livestock in the night, attacking them and potentially dragging them back into the underworld. But in the daylight hours they would retreat once again into the mountain, hiding from the world beneath Teide, which the people knew to be a gateway to the underworld.

Achamán was normally unconcerned with Guayota and his followers. Though they attacked people in the night, so long as Magec rose in the morning she would scare the beasts back into their mountain and force them to hide from the world. So long as Magec and Achuguayo were in the skies, the people could be unafraid of the terrors of the deep.

But Guayota was not happy with this fact. In Guayota’s opinion, his followers should be free to reign terror on the mortal world and bring darkness to the surface. Though the sun often drove his dog-like minions back into hiding, Guayota was growing tired of bending to her will. And so, one day, Guayota decided to make his move.

There was a terrible sound and the gateway of Teide split open, ushering forth Guayota and the Tibicenas into the skies as they attacked Magec. Overpowering her, they soon took Magec and dragged her into the depth with them, forcing Magec under Teide and trapping her in the underworld, forcing the world into an everlasting darkness.

The people prayed to Achamán to save them from this fate. Without the sun they couldn’t survive and in the darkness the Tibicenas were free to terrorize them unhindered. And with their pleas, Achamán decided that something had to be done with Guayota. Coming in the form of rains, Achamán purged Guayota and the Tibicenas from the world and pushed them back into their domain beneath Teide while bringing Magec back out from below and setting her free, allowing her to flee to the heavens where she belonged.

The people thanked Achamán for his deeds and worshipped him as the one who would protect them from Guayota should he ever try such a thing again.

And that’s the one story we really have from the Guanches. Everything else we know of the peopleand have learned of them has been what was adopted there after they were exposed to the world of the Abrahamic religions. Chaxiraxi, the sun mother, eventually even became identified with the Virgin Mary, who the Guanches believed was an embodiment of their sun mother.

But before that cross pollination, we can see a pretty basic idea of how all mythology formed. If you decide that you don’t want to draw from an existing mythology, follow the basic frame work of the Guanches. Find a natural phenomenon and give it a face, whether it be the rain, the sun, the moon or mist falling down a mountainside. Because that is how all mythology really began, people seeing the world around them and giving it a name. Before there were angels and virgin births in the Canary Islands, there were gods living in the mountains and demons living in volcanoes. And it’s all simple, in the end, because if you ever looked into the mouth of a volcano or watched it erupt…

You’d be pretty sure there were demons there too.

(I write books. Next up, I’ll present a little view into the fictional history of that world with the first entry in the Alterpedia Historia and Alternative Mythologies tackles West Africa in a multi-part series.)