One of the things you end up doing a lot of when you’re not feeling your absolute best is just taking in some media. Maybe there’s a book you’ve been wanting to read, a movie you’ve never seen but always wanted to, or a wiki that you’ve decided to memorize. Whatever it is, you’re probably going to get way too invested in it because you can’t really do much else. Sitting as a puddle that used to be a person under the influence of medications, I’ve watched some lackluster movies in the last few weeks. One day I may, haunted by my flashbacks, tell people about the time Bedazzled’s ending made me tear up because I was too gone to know better.

But one of these lackluster movies actually made me think about a real problem that real people have. A lot of readers and writers encounter a problem with a situation called the passive voice. The passive voice is when your characters are less actors in their own life and decisions and more passengers along for the ride. A lot of advice columns will tell you to avoid it like the plague and, really, there’s not a whole lot to say on that subject anymore. The best piece of advice for this is already on the internet if you’re willing to look for it: If the sentence can be finished with “by zombies”, it’s a passive sentence.

This advice was brought to you by Zombies.

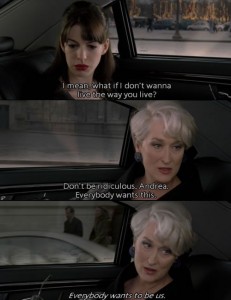

But during my lazy watching of lackluster movies I came across a unique case that needed to be pointed out: The Devil Wears Prada. In The Devil Wears Prada we see a rare (but not unique) situation… a passive-aggressive voice.

The Passive Voice Loophole

For those of you not familiar with The Devil Wears Prada, the plot is fairly standard. Andrea (Andy) is a recent college graduate looking to become a writer who has been applying to magazines for some time. After being repeatedly turned away by other magazines, she happens to land an opening at a major fashion magazine, “Runway”. This position is as the assistant of the magazine’s editor in chief, Miranda. The crux of the premise, and the namesake, is the fact that Miranda is the boss from hell. Andy has many problems with fitting in and all of these are exacerbated by Miranda’s demanding and unreasonable personality.

As the plot goes on, Andy is forced to change who she Is to try to fit into Miranda’s world and finds herself slowly being alienated from everything else she loves as a result. Before long she has made a habit of breaking promises, flaking on her friends, and eventually losing them, and her boyfriend, due to the stresses of the job which is consuming her life. As we reach the third act, she has lost almost everything of her old life and is now fully in Miranda’s world where she finds that Miranda is a miserable person who is willing to do horrible things to maintain what she has. Miranda seemingly cares about no one but herself, and she reveals to Andy that she sees the same in her.

According to Miranda, the decisions Andy has made make her no different than her. Confronted with this idea, Andy quits and returns to her old life, rejecting Miranda’s world and saving herself from going down that same road. Returning to her old boyfriend, Andy is forgiven and he implies there’s still a chance for them to continue their lives together in another city – a prospect Andy seems interested in.

The messages are clear. You shouldn’t sacrifice who you are just to fit in. You shouldn’t yield your will to other people. You shouldn’t put career ahead of everything else. And, most importantly, you shouldn’t allow yourself to be corrupted by the lure of a better life.

Just one problem: none of that is actually what you get. Despite her friends abandoning her and accusing her of having changed, Andy is never actually shown changing or being corrupted. She merely puts on new clothes and continues to do the same thing from beginning to end, right down to the final scenes. And what does Andy do, exactly, in the entire film? What everyone else tells her to do.

You see, while certain rules of writing are pointed out everywhere, those rules are often bent, broken, and ignored in the actual profession. For as many people as you see warn against the dangers of passive voice and passive characters, you’ll find just as many examples of these things existing in the professional market. And, while Andy was not written strictly with a passive voice, that’s merely because she was given a loophole. Andy is a character written in a passive aggressive fashion.

Almost nothing that Andy does throughout the film is actually her decision. In fact, for the most part, all conflict is generated by who gets to call her shots. Her friends berate her for most of the back half of the film for how much she’s changed – but all she’s really changed is her wardrobe. Andy is still the same person that gets told what to do by others and does those things no matter how unreasonable they may be.

In fact, even as we see her finally stand up for herself by quitting from Runway (one of only 3 independent actions she makes in the entire film), she’s next sitting across from her boyfriend who proceeds to make a decision for her again. Happily, he informs her that he’s going to go to work in a restaurant in Boston and implies that she should come along with him. Appallingly, she seems to think this is a great idea. Despite spending most of the film telling her how her career shouldn’t change her entire life, when he does the exact same thing it suddenly becomes charming.

The reason is because Andy is everything a character written in the passive voice would be. Andy doesn’t really do anything, she has things done to her. Even her successes are largely based on the work of others, with the turning points in her career being the result of actions from supporting characters. Andy’s one true success is knowing who to ask for help as she flounders and flails around wildly in frustration. Of all the things that Andy did in the film, the only thing that actually involved her making the decision, executing that decision, and providing results for herself… was walk away.

And that’s a passive voice character, that’s as passive as you can possibly get. Everything but quitting can be described with “by zombies”. Andy is given a job unexpectedly… by zombies. Andy is berated for not fitting in… by zombies. Andy asks for help and is rescued from her situation… by zombies. Andy is kissed… by zombies… and caught… by zombies… and told she has “changed” and has become an unrecognizable person… by zombies.

One would have to assume that the book it was adapted from features an actual insight into her decision making. It would be almost impossible not to show your protagonist’s motivations across a full length novel, even if you tried. And for the most part, I like to believe that such a novel (where we never see the character’s motivations) wouldn’t have seen the light of day or been given the attention it received. So I just have to assume that we know the inner workings of Andrea and see her make actual decisions in the book itself. But the character we get in the film is a perfect example of the “passive aggressive” loophole.

In the passive voice, things simply happen to characters and they rarely show agency in their actions. But to try to get around this, some writers, even professional screenwriters it seems, use a little loophole. They resolve this by amplifying the reaction of the characters around the passive character to artificially inflate their culpability. In Andy’s case, while she never actually did anything proactive, every character around her behaves as if she has been doing these things of her own volition. The result is that the character, while still incredibly passive, is being presented as though she was acting independently. This creates an inflated, artificial sense of conflict, which doesn’t really pan out.

One great example of this is in the third act of the film as Andy is taken to Paris by Miranda for a major event. Emily, Andy’s coworker and sometime antagonist, was preparing for this trip throughout the first half of the film and was set on it with every fiber of her being. Due to a set of events (which Andy had no part in), Emily loses Miranda’s faith and is taken off of the trip. Having decided Emily isn’t going, Miranda then tells Andy that she’s going to take Emily’s place. This is presented as if there is an actual choice here, that there is a decision which is being made by Andrea to take this opportunity – but it’s not an opportunity Andy shows any sign of wanting at all and, when she initially resists, Miranda uses leverage on her to make her go.

This one moment is then used to completely derail Andy’s life and demonstrate she’s “gone to the dark side”. Everyone around her immediately begins to treat Andy as if she has done something. But the fact of the matter is, the choice was artificial – either she’d gone, or she’d have lost her job. In fact, even if she had decided to simply be fired, the moment she’s ordered by Miranda to tell Emily that she’s going in her place is broken up by Emily being run over by a car. Not only did Andy not have to make a choice, as there was no real choice to be made, but the situation(s) that resulted in Emily not going were completely beyond Andy’s control.

Her coworker was run over by a car… driven by zombies.

To an outside observer, it’s perfectly clear that Andy has not only not done anything wrong – she’s done nothing at all. Her greatest sin in the entire film was saying yes instead of saying no. But this is enough at this point to have her boyfriend decide to leave her, her coworker decide she’s a backstabber, and Miranda to (and this is where even my drug addled brain lost it) claim that Andy was “just like her”. Towards the end of the film, as Miranda has done something completely atrocious, Andy questions how she could do such a thing and Miranda responds “you’ve done the same… to Emily.”

The problem here is that the conflicts come across as completely artificial because of Andy’s passivity. While every character around her insists she’s gone to the dark side, she really hasn’t done anything except what she’s told. This sort of conflict isn’t completely unwarranted, she could simply reject this notion and stand up for herself at some point in the story. But by the end of the film, not only does it come across that Andy has accepted this narrative, but we’re supposed to accept it as well. During her last conversation with the boyfriend, Andy muses that she didn’t know why she stayed with the job so long and her boyfriend (real charmer) says she did it for the clothes, the shoes, and the lifestyle.

Andy doesn’t even try to challenge this, and implicitly, we’re not supposed to either.

Writing a character who is passive is not, in itself, a sin. However, writing a character that is passive and then trying to make it appear as if they have actually done something, that is. Your conflict will become artificial, your character interactions will become forced, and, if you’re truly unlucky, your audience is going to catch on and reject the whole thing. There’s a trope out there known as a wall-banger – a moment where a story has frustrated you so much that something has to be thrown or slammed into the wall. And, in my opinion, if you spend the entire story representing how lacking of a will your character actually has while simultaneously having every character insist they’re acting on dark desires…

A wall might not be enough.

(I write novels. My characters have agency. I’m petty sure the book version of Andy probably did too, but I can’t be sure. If I’m wrong, be sure to tell me on my twitter account.)