Recently I wrote about the potential drawbacks of immortality and, funny enough, I haven’t stopped thinking about mortality since. We’re the only animals on this planet that understand we’re here for a finite time. From the day we first learn what death is, we know on some level that it’ll eventually be our turn. When we’re young, it doesn’t quite occur to us day to day, but we still feel it on some level. And when we’re older – well some of us can’t stop thinking about it. The fear of death, in one way or another, shapes our very lives as we decide how we want to spend what little time we have here.

And a result of this, as I mentioned last week, is that the very idea of religion is often an attempt at finding a way out. Mythology has often dealt with the ideas of the natural world and explaining what’s around us. We have gods of thunder to explain why lightning streaks across the sky and the world rumbles like the clash of a mighty hammer. We tell stories of how all the world’s ills came from a box opened in a moment of curiosity or eating the wrong fruit. It’s in our nature to personify the forces of the world around us. But your religion, if you’re honest with yourself, is almost always about your mortality – a fact I forgot to mention when writing on how to go about treating the faith of fictional characters.

Many would say that your religion is what you believe in, but there are systems of belief out there which are fairly anti-religious. Others would say that a belief in a god of some sort is required, but there are forms of Buddhism with no gods to speak of. And, of course, some would say the rites and rituals are what make a religion and that you’re otherwise just spiritual – but once again I don’t quite agree. I’ve personally interacted with people who aren’t Wiccan but will still practice some of their rituals. To them, it’s simply a mythology, even if it’s a religion for someone else. And we’ve all known people who hold a religion but don’t stick to the traditions. In fact, many think that someone who does try to stick to all of their traditions zealously is not of sound mind.

So, while these religions may have all of those beliefs and rituals, the one thing holding them above simple mythology is that people believe in their version of the afterlife. And the funny thing is, because it’s so important to these belief systems, that afterlife says a lot about the people that believe in it.

The Next Step

Whether someone believes in heaven, hell, reincarnations, or none of the above – most belief systems establish what’s supposed to happen and why. Someone who has accepted Christ is supposed to go to Heaven in Christianity. A Buddhist who has found enlightenment ostensibly goes on to Nirvana to be released from the cycle of reincarnation. The number of paradises described for the “worthy” are too numerous to count. And, if you’re not the best of people, most religions also have a place for you too.

But while this is something that influences how the people behave in those cultures, it also reflects how they think most of the time. If you believe in an afterlife, you generally believe that people deserve to go there. And the reasons why you think they deserve to go there are a big part of your philosophy because, if you’re an honest player, you think the same rules apply to you. As a result, even if it doesn’t necessarily cover the individual’s behavior, the afterlife does reflect the philosophy of the religion as a whole.

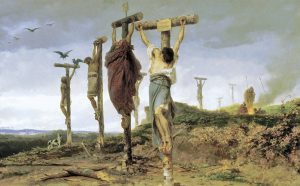

Christianity, though founded on the teachings of a man preaching forgiveness, rose during a time when persecution at the hands of a higher power was pretty common. Through both a hardened world view and a deep desire for some form of retribution, the Christians introduced a much harsher form of Hell than the Jewish faith had before. In fact, ironically, the Jewish form of “hell”, Gehinnom, is temporary for people as their soul is cleansed and they eventually proceed to Heaven. Does this mean that the Jewish are more forgiving than the Christians? Not necessarily. But the early Christians were an understandably militant bunch and felt embattled through those first few centuries when they codified their beliefs.

Not far away (though much more ancient), the Egyptians also had a unique view of the afterlife that reflected several things about their culture. Though we today often argue that you “can’t take it with you to the grave”, the Egyptians not only believed it – they encouraged it. On top of the mummification that would preserve the body for use after death, many tombs would be filled with possessions to be used as well. This wasn’t merely decorative, either, as the Egyptians demonstrated a belief that the afterlife was more of a continuation of this life rather than a distinct existence. The body, the possessions, and the tomb were there to be used by the deceased for the rest of their eternity. Each tomb acted as a connecting point between our world and the next and it would act, in part, as the home of these people should they not push ahead.

The act of mummification was telling in a few ways. In trying to preserve the body, anything they knew would decompose quickly would be removed. The brain, lungs, and many other parts would be extracted, dried out, and put in containers – but the heart would be left behind. The reason for them to leave the heart behind was that the Egyptians believed the soul, and thus a person’s intelligence and emotions, was kept there and that it would be needed in the next world. The soul, still within the body, would be needed to get to where they were meant to be, because in the next world your work still wasn’t done.

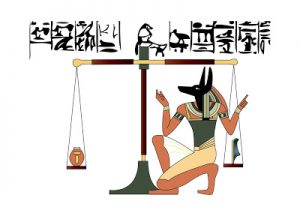

Carrying their soul through the underworld, past monsters and strange phenomenon, Egyptians were to meet with Anubis and have their soul weighed against “truth” and “justice”. If their hearts were too heavy, full of sin and doubt, they would end completely at that point. However, if their hearts were balanced with that truth and justice, embodied in an ostrich feather from the goddess Ma’at, they would be considered worthy to continue on. Given permission to pass, they would then take a perilous journey further into the lands of the underworld before reaching a paradise ruled by Osiris. Thus, while many would take this journey, others would stay close to their tombs and avoid the danger of trying to reach this paradise.

It’s telling because it means that the Egyptians felt that death wasn’t really the end of their trials, but the beginning of new ones. Those who had much to take with them to their tombs could be comfortable there, but the others were generally expected to undergo great danger to get to a better place. They would be judged for the way they lived their lives, subjected to frightening things, and then expected to continue on even after being found worthy. And all of this shows a culture that valued not only a sense of right but perseverance and dedication.

And this is the sort of thinking that really goes towards shaping those cultures we create (both in our world and our fiction). It’s not simply enough to create gods for our fictional characters but also create a concept of the afterlife. And, more importantly, that afterlife has to make sense in a real world context. I mentioned during that post on fictional faiths that the Klingons were explained by a desire to achieve glory to go on to what amounts to an alien Valhalla. And many would say this makes sense because we know that the Vikings did the same – but rarely do we stop to ask why the Vikings believed what they did.

Seen as people who pillaged, raided, and razed villages to the ground – it’s easy to understand that people would see Vikings as simply war-like. But for all of their aggressive acts, Vikings weren’t particularly known for conquering. And, in fact, while dying in battle was a method to get into a glorious afterlife, there was another that gets overlooked – drowning. Though they did worship a god of war, Odin, he was also a god of wisdom and they weren’t the only ones. Yahweh, before becoming the supreme deity of Judaism, was seen as a regional war god for a time and yet no one holds that against them. So, the fact is, when stepping back and looking at their afterlife and their behavior, the Vikings didn’t necessarily value the violence but rather the cause. These were people who lived in a place where it was hard to survive and they honored the people who were willing to leave their homes and potentially die for the good of their villages.

Bringing that back to our fictional comparison, it raises some questions about why the Klingons became what they were. The Vikings had a reason for becoming dedicated to the idea of Valhalla, it was their attempt to survive harsh conditions. But what brought the Klingons to their place? What made violence a virtue? Audiences generally don’t ask these questions out loud, but they’ll feel it on an instinctual level – the fact it doesn’t quite feel natural. Individuals may be looking for thrills and adrenaline, but no society is into violence just for the sake of violence. So while it’s not completely necessary, it wold be beneficial to keep such things in mind. Because, otherwise…

Fictional cultures might be missing some context.

(I write novels, which will hopefully outlive me. I also tweet, they will last for the 5 seconds they stream by your feed.)