We live in a world today where having a “franchise” is incredibly important for writers of every kind. Films are the most visible of this, especially in a post-Avengers world, but it’s also long been true of other forms as well. Writing a film that removes all possibility of a sequel or spin-off of some sort is generally a good way to get executives meddling in your work. Having a television series that couldn’t somehow generate a spin-off or be part of a “universe” is gradually becoming taboo. Comic books and video games are expected to be part of a long running series, sometimes to the detriment of both. And, even as an author of novels, someone who manages to land a book deal is signed for more than one book of the same series. In fact, one could argue that even if you only make stand alone projects, if they keep getting money – you are the franchise.

But that leads to the inevitable problem of prequels and sequels struggling to succeed. It’s well known that making a good sequel can be pretty difficult and making a good prequel is thought at times to be nearly impossible. More than once I’ve heard other writers and critics talk about how a good prequel is something that just can’t be done. And sequels, though recognized to be capable of being good, are generally approached with great caution. Yet, it’s impossible to ignore that some series of books and similar projects wouldn’t have been quite as good as a single stand-alone entry. Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and many others just wouldn’t have been the same without multiple entries building their lore. Though, a word to some, this doesn’t mean you divide a stand alone book into multiple films.

Still, despite these successes, you would be much harder pressed to find a prequel that everyone can agree is somewhat good. In fact, I’ve had prolonged conversations with people who insisted that prequels not only fail but tend to ruin or cheapen the thing they were a prequel to. Frankly, with Star Wars showing us how much prequels can be utterly loathed, you couldn’t blame someone for that idea. And yet, many who hated the Star Wars prequels have had to admit that they were pretty fond of… a Star Wars prequel.

So the question comes, just what exactly divides good prequels and sequels from the bad? When the topic comes up people tend to have a laundry list of things that a prequel or sequel needs to be “good”. However, the items on those lists are usually things you need for any story to be good anyway. So why would it be that it’s easier to write a stand alone than it is to write good sequels and prequels, and just how did the ones that pulled it off manage to do so?

In my opinion, it boils down to one thing: resolutions.

Frayed Edges

Everyone who has ever tried to write anything will know that any good story requires a beginning, middle, and an end. And, unfortunately, that means taht any good story is generally self contained and doesn’t leave open an opportunity for the stories that would spin off from that one. How is it you can write a new beginning to a story in a prequel if that beginning was already well established? How can you write a better ending to the story if you did your job and had the first ending wrap up to everyone’s satisfaction? It’s generally the thing that derailed sequels for years because it was incredibly difficult to make a sequel without undoing whatever you had done the first time around – leading each entry in a franchise to feel like the reheated leftovers of the last.

So to make a good sequel you have to do something that is difficult for most people to grasp intuitively – leave your resolutions alone. Your central plot in the opening entry of a franchise will have the most interesting plot you can think of at that time usually. It’ll be something that you felt the most attached to in that moment. So to make a new story with the same characters without that particular plot device can be difficult for people. But by unraveling that resolution and trying to tie it all back together again you would end up damaging the old story while making your new story seem boring, lackluster, and unoriginal. In essence, trying to recapture that original feeling will destroy the feeling in the process – and that’s not good for anyone.

Some would argue that it’s nearly impossible to create continuity between two entries without that recurring plotline, but they would be wrong. In general, the most successful franchises with multiple entries are the ones that do something others just can’t imagine doing themselves by promoting lesser plots to the main event. Consider for a moment that, for the majority of the franchise, Voldemort was actually the b-plot (sometimes even c-plot) of the Harry Potter franchise. He was there, providing continuity and constantly looming, but wasn’t really central to the events at that time until he came back. It was basically foreshadowing the plot of books and films that wouldn’t appear for years while allowing the central plot to run its course within each entry. The same even holds true for the Avengers – a franchise no one thought would work when it first started, but was almost literally tailor made for achieving this effect.

Like with Harry Potter, the most important plot devices to the MCU are not at the forefront of early entries in the franchise. The characters are vibrant and likable, the self-contained stories are serviceable, and the villains (while sometimes bland) are good at providing a foil for their time in the franchise. But the thing that really ties the MCU together is that what was a minor plot detail in one movie will become a major detail in the next. In fact, the surprise hit they got on their hands with Avengers was the culmination of three separate B-plots being woven together. Loki starts manipulating a member of the supporting cast of Thor to study the Tesseract from Captain America which results in a situation that forces Shield to activate the Avengers initiative they talked about through the first two Iron Man movies.

Is this the only way to make a good sequel? Of course not. Is it always going to work? There are no promises. But is it more likely to work than simply reheating an old plot device and destroying the resolution you had in the first place? Hell yes.

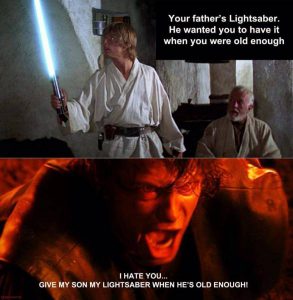

And preserving resolutions isn’t just about moving forward but also moving backwards. One of the greatest problems (if not the greatest problem) of prequels is that resolutions within those movies often mean absolutely nothing under most circumstances. Taking one of the most loathed prequels of our era into consideration, everyone knows from early on that Anakin Skywalker is supposed to become one of the most famous villains of all time, so it becomes difficult to watch him fumble through his more innocent days and even harder to sympathize with him when he starts to lose who he was originally. It’s not that the story of an innocent kid gradually being consumed by fear, grief, and violence is a bad story – it’s that we know the outcome before you even begin so it’s hard to buy the early part of his life. To the audience, the “original” was the villainous outcome while the good guy is the unbelievable aberration.

But, from the same franchise, we find that most people are much more pleased with Rogue One. The reason is simple: every important character’s fate in that prequel has an opportunity for an unknown resolution. Despite being a prequel (and a fairly direct prequel at that), each character arc within Rogue One has a complete beginning, middle, and end without interfering in anything that happens in the rest of the franchise. It’s self contained, despite leading immediately into the opening of the very first film of the franchise, and that makes all the difference.

This can be a bit of a hassle for some creators, but a necessary one. If your stories don’t reach their resolutions and remain somewhat self contained, they can’t support other entries in the franchise. And, while this is something a lot of people know on a level, the urge to try to get around this can be incredibly strong. Some writers will try to avoid violating resolutions by simply not having them – and this is a terrible idea. Generally people are savvy to when you’ve tried to prep for a sequel or the original by leaving a gaping plot-hole open or ending on a bizarre cliffhanger. This simultaneously prevents your next entry from having a solid beginning and prevents your first entry from having a reasonable end. In fact, sometimes the attempt to do it will make you look stupid as you behave like there’s a guaranteed sequel…

When your audience wasn’t too thrilled with the first.

(I write novels, I hope to have made each entry as self contained as possible, but I admit to ending on darker notes. In the meantime, if you want to see me make something really self contained, twitter only gives me 140 characters.)