One of the big questions for building a world in speculative fiction is what languages these characters should be speaking. We’ve seen so many softer science fiction properties fall back on the universal translator concept, but that isn’t always the case elsewhere. Joss Whedon’s Firefly franchise made a point that everyone speaks two languages, English and Chinese, and that most of them usually cursed in the latter (to get around censorship). The film “Arrival” spent a great deal of time focusing on just how exactly you can understand an alien civilization with a wholly different way of thinking and writing. And for all the flak that Star Trek: Enterprise got, it was the first time in the franchise where no one could deny the communication officer’s job was damn near impossible at times.

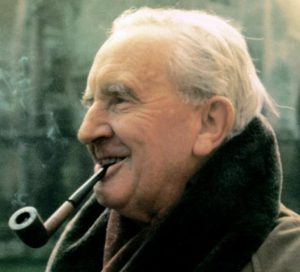

But in the fantasy setting the question gets even more complicated. These are ostensibly creatures that have lived on the same world we have and they’ve been trading linguistics with us for as long as we’ve known they exist. Few languages in the real world are entirely isolated from each other, loan words exist in almost every corner of the world. And even if isolated, languages have evolved to such a degree within our own history that certain languages would be completely unintelligible within no more than a millennium. Because of this, it’s hard to know what exactly Elvish, Dwarvish, or Orcish are supposed to sound like. In fact, while a lot of these have versions, the best example of someone coming up with languages for these races was done by a linguist who did this kind of thing for fun and had an obsessive compulsive need to world build.

But, if you think about it, you don’t have to be a Tolkien to come up with a believable fake language. After all, it’s supposed to sound like gibberish…

Communication Gaps

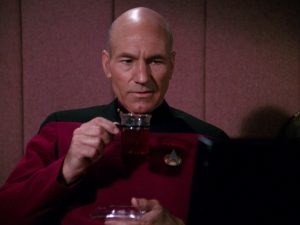

Within human languages there are so many distinct dialects that it would be impossible for any one person without the assistance of one of those “universal translators” to be able to understand all people. Yes, there are always likely to be translators available for people who speak one of the more prevalent languages, and more people learn certain languages than others. But the idea that there is a so-called “human tongue” as you find in many speculative fiction works is a little silly at best. In fact, one thing to bake your noodle is that, since all of them are using universal translators, Captain Picard may have always been speaking French while the universal translators just made him sound particularly British.

And, in fact, even when you are all speaking the same language it is incredibly difficult for people to understand certain dialects. While most people from the major English speaking countries of the world would have an okay time understanding each other, it’s generally accepted that any American tourist traveling the UK is going to run into at least one dialect they have no damned way of understanding. In fact, if you’re really unlucky, some sources say there are at least five you’ll struggle with.

So when thinking about other creatures that may live on our world there are a few factors that would make them even more unintelligible in their own tongues. Should they be using a language similar to one of ours it’s very likely that they would be using a completely alien dialect born out of being isolated from humanity for potentially generations to outright millennia. They could even be using a dialect of a language long dead to the rest of the world, last spoken in a time when they were closer to us, or be using one that they created all of their own. While it would be unlikely that their language sprang entirely independent of humanity’s languages, just given proximity alone, even some minor deviations in the past resulted in Indo-European languages becoming completely distinct from each other. For anyone who doubts that related languages could sound absolutely different from each other, keep in mind that Icelandic is in the same language family as English.

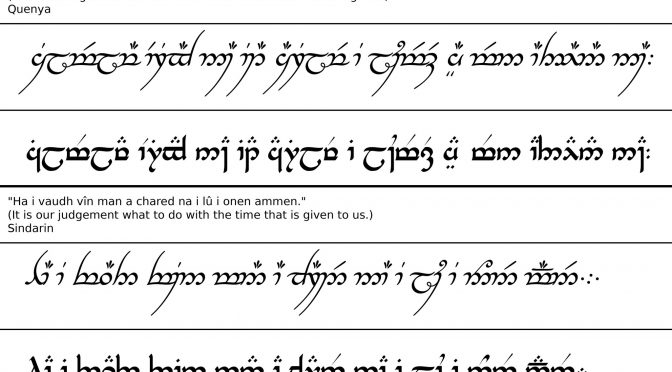

So, in the end, while Tolkien certainly did it expertly, the real requirement for making a believable fictional language is that it follows some basic rules, starting with making sure it does sound somewhat like gibberish to us. The most common mistake I’ve seen with people who try to cook up such fictional languages is that they start with a basic language that we have and then think that they can’t make it sound too distinct from ours. The idea behind this approach is that if there’s something still partially recognizable then that would somehow make it feel real. In actuality, it should be nearly incomprehensible, constructed in such a way that we’d be able to pick up only a few loanwords at best (and not necessarily loanwords they took from us). In fact, outside of those few recognizable words, the only thing it should sound like is itself, maintaining internal consistency while only having a passing resemblance to regular languages.

The second biggest factor is that sense of continuity. Within the language there should be a set of sounds which you hear with some manner of frequency. There should be rules to when they show up, how often, and what they really represent. To put it in another way, is that particular grunt the Orcish equivalent to a vowel? If it is, then it should show up as frequently as a vowel would. Constructing an alphabet in and of itself is easier than a full language (alphabets lack syntax) but would quickly give you a series of sounds that can be strung together to create that distinctive feel. Maybe it’s not the way a natural language would evolve, but it would, at the very least, be its own thing.

The more difficult parts would be to construct a vocabulary and a syntax, both more involved but still well within the reach if you’re doing only limited dialogue with it. Vocabulary is generally a matter of taking some time to work out a few choice words. Rarely do people know more than a couple thousand and generally most conversations make use of only a couple hundred at any given time in casual conversation. And, as for syntax, a little study into our own cultures can show the various ways we’ve done it and give you an idea on how to do it yourself. It wouldn’t have to be a perfect thing, you’re still creating gibberish, but the difference between a good fictional language and a bad one is taking the time to establish those kind of ground rules. Is it perfect? Not at all. But effort always shows.

Admittedly, it’s a weird thought to have, but I’ve noticed so many people who either half-ass it in an effort to avoid looking bizarre or convince themselves not to bother at all because they can’t match with the likes of Tolkien. Some resolve this by simply hiring a linguist, and those skilled few have made fantastic contributions to fictional worlds. Game of Thrones’ television adaptation, having only a few phrases from the original books to work with, hired a linguist to fill in these blanks. But it feels as though, for those of us who can’t afford to hire that kind of linguist, it’s not really such a crime to wing it with a little careful study and some effort to remain internally consistent. After all, given a few centuries…

The rest of our words won’t make much sense either.

(I write novels and dabble in screenplays, which haven’t had need for constructed languages yet. Meanwhile, I accidentally create a language through typos on twitter – though never as well as covfefe.)