In a time when every studio needs to have their own franchise of interwoven properties, Universal studios came to answer it with their “Dark Universe“. Starting with The Mummy (a decision they may be regretting given the reviews), the plan was to have Universal bring together all of its major “movie monster” properties in the same way that Marvel and DC had been doing over the last few years. Bringing together the likes of The Mummy, Dracula, Frankenstein, and several other properties, the hope was to create something with the kind of cross promotional marketing power as an Avengers or Justice League.

But, while these properties are essentially chosen for their iconic status, they’re also chosen for being ostensibly within the same genre. They are, after all, old school horror icons which have been part of the cultural mindset for generations. Each of them, a movie monster that had been in film since the days before color, represent something with instant brand recognition. And for the longest time all of us have grouped them within our minds as being essentially a part of a single genre.

But this has always been something I have a bit of a problem with because, outside of the films, Frankenstein doesn’t really belong…

Universal’s Monster

Since before many of us were even old enough to be able to read the original books several of these properties were based on, we knew these monsters. Dracula is as iconic as a figure in literature and film as you can get and everyone has some idea of who he is, likely rivaling the recognition of any fictional character you could find but rarely included in such polls. The idea of a Mummy’s curse has been around for as long as we’ve realized the Egyptians buried their dead in that fashion, with several instances of real world archaeologists coming to strange ends due to opening a long sealed tomb. And, of course, everyone knows Frankenstein – even if they sometimes forget that wasn’t the name of the monster.

And since all of these creatures exist strongly within the public domain they’ve been used in stories across the board. You can find these creatures in movies, video games, comic books, novels, and television shows throughout the last century and all strongly influenced by the iconic images that Universal put forth so long ago. The Dracula most often found in the cultural mindset, the one that we base costumes on and the terrible accent we’ve all made an impression of at least once in our life, was distinctly a creation of Universal. Similarly, the very look of Frankenstein that springs to your mind when you think of that word – the green skin, flat topped head, bolts in his neck and the lumbering motion – that was all on Universal too. But the thing that Universal really changed about Frankenstein, in the end, was the genre we associate it with.

And, at first glance, it would just seem that genre would be “horror”, but it’s actually a little more defined than that. Every one of those adaptations that includes Frankenstein’s monster with other creatures puts him roughly in the same field as creatures of fantasy. He’ll generally be portrayed coming into conflict with vampires, dealing with mummies, or encountering witches. He is, as far as most imaginations are concerned, a dark fantasy creature – a flesh golem brought to life by an act of necromancy, who has more in common with the undead than with the living. And this is fair, because the very concept behind him is fantastic in nature. But as I often like to point out, just because it looks fantastic doesn’t necessarily mean it’s not scientific. And, while our imaginations may put him in a dark fantasy, the original book was a soft science fiction novel – one of the very first. In fact, it could be argued to be one of the most validated soft science fiction novels ever written.

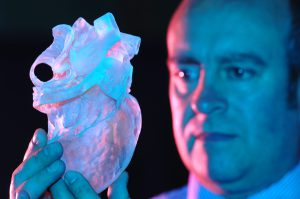

Though lacking the hard realism that we often identify with science fiction, Frankenstein’s softer approach to science fiction has proven to have some mileage in the modern day. Though missing much of the details and complexity in the work that wold make it seem more real to us, the truth is that we’re growing ever closer to a world where such a creature could be created. As unreal as the premise itself has sounded for so long, we lie in an era where transplant technology is growing in complexity and reliability almost every day. Great strides have been taken to ensuring that transplants are being rejected less, getting better, more consistent results, and that more complicated things such as hands and faces are being transplanted as reliably as organs. And, when something like a heart is finished being transplanted – we restart it with electricity.

In fact, even the most extreme and bizarre elements of the concept are becoming possible over time. Giving the creature a brain, the least possible and most unrealistic of the process, is slowly becoming something that people think may be possible, In fact, though much of the medical community believe him to be completely misguided, a doctor is currently working towards doing complete human head transplants and experiments have already gone into transplanting the heads of rats. Though we’re miles away from actually achieving it (most of the medical community agrees it’s way too early for him to even try), it’s something that people are working on for a variety of reasons.

In fact, what Mary Shelley’s monster lacks in realism is in the details that soft science fiction isn’t generally held accountable to, details she likely couldn’t have known in her time. The first is that brain death is the final note and that you can’t simply transplant the brain of a dead person into this new body because the brain’s degeneration after death is irreversible. The second detail she missed was that transplants are more complicated because of the potential of rejection and structural issues. And getting that new limb moving requires connecting each underlying piece of it in exacting detail from the blood vessels to the nerves and all of the connective tissues. Essentially, while the actual act of constructing a body from the individual parts is becoming more feasible, the thing she missed was the exact methods in which you would do it. In fact, as we continue to improve those methods, the only reasons why something like a Frankenstein monster will never be created are the ethical concerns and the fact that it will be unnecessary once the technology is ready to do it.

In a stroke of irony, the very technologies that would make the monster possible are the same technologies required to make such a creature unnecessary. As we move forward in learning how to repair the nervous system, keep organs viable for longer periods of time, and fill in the spaces between damaged tissues, we’re getting closer to simply being able to grow new tissues almost from scratch. The use of 3D printed organs is becoming more possible over time, stem cell research is leading towards the ability to simply repair some organs on site, and we’re quickly getting closer to the day when you could simply clone a new body to transplant that brain into. And, while some of these techniques present some ethical concerns, they would prove to have better results than the monster created in the book of lore. In fact, one of the greater ethical concerns is whether or not a completed clone would be a living thing of its own.

So, in the end, ‘while it is a softer sci-fi, the idea that Frankenstein is considered a work of fantasy in the minds of so many has always bothered me a little. Though I’ve always felt that there was room to have such things cross over (obviously as a sci-fantasy writer myself), it feels as though the science of Frankenstein was waved off as simply magic a long time ago, turning a creature of questionable medical and scientific ethics into yet another kind of undead. And, frankly, in our modern culture, where the undead have become such a saturated market, it almost feels like we need to recognize there was always more to Frankenstein…

Than a quotable scene and a slew of hand-waving.

(I write novels. There is actually a sci-fi take on some of these concepts in one of them. I also write tweets, which are also written by a reanimated corpse.)