Pacing, it’s vital to your stories and it will often determine how well received it’s going to be. Even the worst ideas can be received well if you have the right pacing, while the best will often tank because “it dragged in the middle”. This, of course, is a bit of a problem for people when they’re first starting out. Pacing is actually one of the most covered subjects in the writing world, but often we still don’t get it right. The three act structure, for instance, is taught almost universally – but translates poorly to some fields and often leads newer writers astray by having them mechanically plot out their beats without any real sense of flow.

So, of course, we’ve figured out ways to make it even more complicated in the modern day. Because we’re masochists…

Modern Pacing – A Double Edged Sword

Many seasoned writers are quick to point out how much has changed within their own lifetimes. Release schedules for books are far faster than they once were, independents are more likely to have a strong showing, and some media has been completely changed by new platforms.

Television is probably the greatest representation of that last one. Once, the pacing of Television was based largely in a 3 to 5 act structure based on commercial breaks and the need to finish a story arc in a single episode. You would have overriding themes over the course of the series, or plot elements that wouldn’t be answered until years down the line, but you would always write towards the idea of making sure that each episode was a complete story on its own. However, as many of you know, the audience of today is prone to binging an entire series in a single sitting rather than watching from one week to the next. You’ll see very few people actually keeping up with a particular series during their weekdays but instead deciding to dedicate a weekend to watching the whole thing in one go. This is something television has never experienced before.

So a trend began where writers, at least those willing to adapt, began to write stories that would be worthwhile for someone who was about to watch 13~24 episodes in a row. Two things became immediately different as a result. The first major change was that it is far more common today for a series to have only 13 episodes per season than it was before. The orders from studios are still roughly for the same number of episodes, but you’ll notice there’s a very common trend for interesting series to take a “mid season hiatus”. It’s a marketing trick, of course, as each half season still produces a roughly contained arc that leaves a cliffhanger for the half season to follow and the executives simply don’t want people to be under the impression they got “less”. But the second major change is where things got really interesting, and a lot harder to navigate.

In the old days of television writing there was a tendency for each episode to potentially have three plots. The A plot, which ran in the foreground, was the major plot of the episode and was the thing that had to be resolved in that single episode arc. This was usually the monster/mystery/drama of the week that was central to the characters for that one case/client/encounter. The second would be the B plot, a secondary situation which happened along side the primary plot but didn’t necessarily interact. This often times featured stories which would flesh out characters who were always present but didn’t have time to be shown to the audience in the A plot scenarios. But then some shows had a C plot, a story that happened not within a single episode or as part of an isolated incident but instead would connect many different events over a relatively long period of time. The thing that throws people off in the modern day is that, for the first time ever, the C plot may become the primary plot as the A and B take a small step back.

A lot of older writers don’t know how to deal with this and younger writers don’t even know where to start.

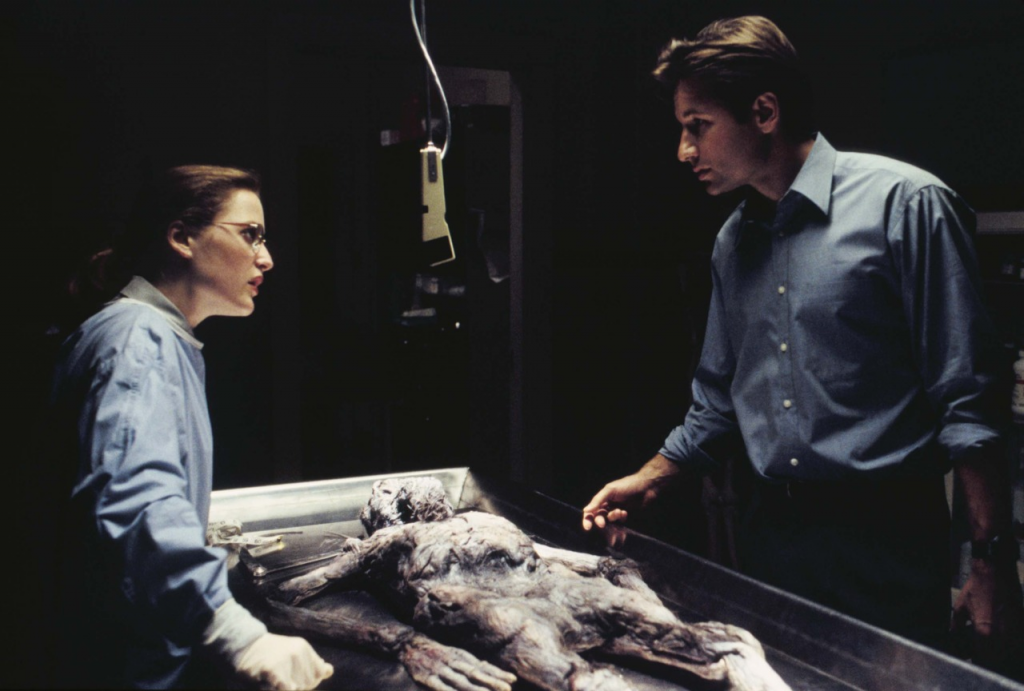

The reason for this is simple. In the old days the C plot was there to provide set up for future episode ideas or to put some aspects of a character on the back burner until someone could come up with a good story using that element. “What happened to Mulder’s sister?” “Who is the Smoking Man?” “What is up with the island on Lost?” “Will Ross and Rachel ever truly be together?” These were all “major” stories that really didn’t matter too much to a single episode’s plot but gave the audience something to anticipate. The issue today is that the audience is going to watch a series in almost a single sitting with no problem. This required the C plot to become the thing that bridged all of the episodes together so that the viewer still had a complete story arc in their one viewing.

There are a lot of ways to pull this off well. The most common right now is to make use of the A plot and B plot elements to continue the C plot. It was once a case that every one of these plots was isolated and insular, an episodic moment in the lives of the characters that they moved on from. However, with careful fusion of the As and Bs with the Cs, you often find a compelling result that keeps viewers watching with great interest. It’s currently one of the leading causes for what some have been calling the “new golden age” of television.

But that’s not to say it’s without its problems. The C plot was once used as something of a tease to stall for a while until someone could come up with a good story to fill the blank. Today, a strong C plot needs to be planned out well in advance or there will be many who realize you don’t know what you’re doing. It also used to be possible to hang a C plot and leave it unanswered for years without worry. But leaving a plot element unanswered for years isn’t possible when your C plot is now the new driving force.

Some would say this makes modern pacing much more rushed and hurried, requiring instant gratification for things that used to be relatively minor details. But it’s not so much that the pacing has become rushed as the emphasis has shifted. Modern pacing worries less about the quality of the plot of each episode and now focuses on the quality of the plot which unites the whole. This makes some things seem much faster, but that was really only because those details were left blank until someone could come along with a good idea. In essence, it requires more methodical planning to achieve a good result now than it did in the past – less about instant gratification than it is about ensuring the audience is invested in your payoff.

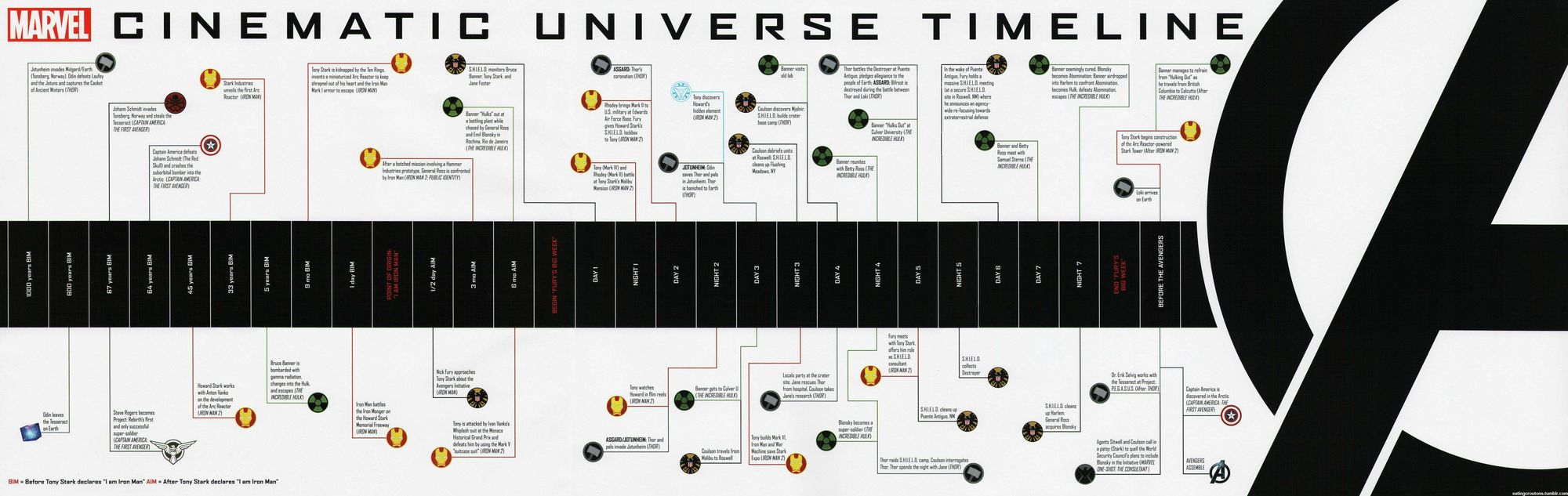

But another problem arises which could be more dangerous to the way we write stories today. The binge viewing pace isn’t unique to television and it actually isn’t even the first medium to adopt it. Novels have long taken a more serialized approach for a variety of reasons, from the fact it’s easier to sell a series to the need for publishers to ensure that they can have more of the same at a steady pace. Film is recently dipping its toes into the water since the success of the Marvel Cinematic Universe made it clear that you could weave together many films into a single shared world. But the MCU got that idea from the place that started this kind of story telling: comic books. And, unfortunately, that’s where we can see some of the dangers of this sort of pace as well.

Years ago comics were built largely on the idea of each issue being a contained story, much like television episodes of the time. But as time went on there was a discovery that radically changed part of their business model. Monthly sales for some issues would be soft, but executives discovered that there was an ability to resell these stories in a trade paperback collection which would sometimes show better sales figures than the month to month sales. The emphasis on trades started to grow rapidly, especially in the first decade of the 21st century and, unfortunately, this inspired a form of pacing known as “writing to the trade”.

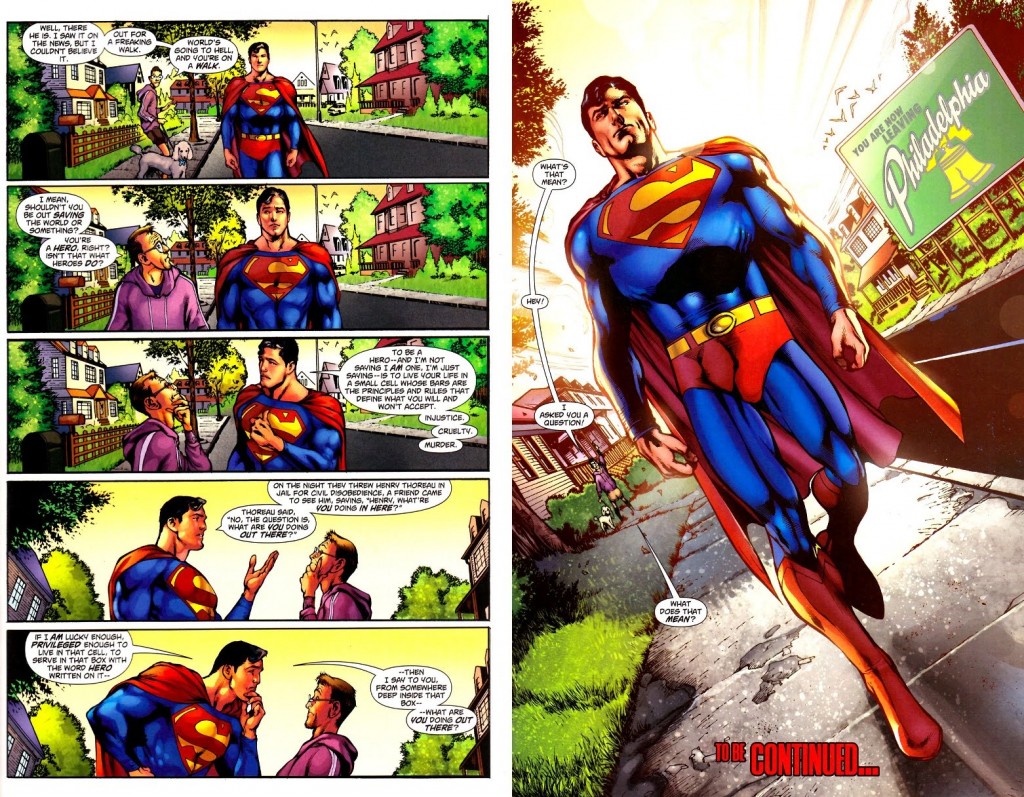

What ended up happening was that the A plot was replaced entirely by the C plot for many of these stories. Rather than there being a connecting thread that would work through one issue to the next, you would instead have the primary plot stretched for 6 to 12 issues. When read in the eventual trade, this was usually a compelling story that was worth reading. But the monthly stories were practically unreadable as a result, fragments of a greater whole that amounted to nothing from one month to the next. In essence, they weren’t just slow, they were slow to the point of making some people decide they wouldn’t even try to keep up with the series until the collection released. One of the worst examples in recent years was a story by J. Michael Straczynski known as Superman: Grounded which spanned 14 issues.

In Superman: Grounded, Superman decides that he has lost touch with humanity and decides to walk like a regular person from one end of the country to the other. He walked, encountered people, had conversations, and walked some more. In essence, he did a slow version of that running scene from Forrest Gump. Except, while the Forrest Gump section lasted a few minutes, Superman: Grounded took over a year to complete. Imagine that for a moment, Superman walking for a year, and then realize that J Michael Straczynski is best known for being the creator and show runner of Babylon 5 and many others. That’s right, Superman walked for over a year under the helm of a guy who writes for television.

So apply that to other things you enjoy and consider how harmful that could be. Imagine if you watched a series that was written specifically for people who were going to watch it entirely in one go and the first act of the story took about 3 or 4 hours and things didn’t get really interesting until around episode 10. To any rational person this would seem like a really stupid idea and not something anyone would ever possibly green-light. But, then again, most rational people would scoff at the idea of trying to stretch one book into 3 movies.

One of the writers of the X-Files said in an interview that they didn’t think the X-Files could be done in today’s climate because the big secrets of the show would be revealed too soon. I propose a completely different problem that may arise from the way we currently write: that the secrets will take the same length of time to reveal but become the only plot available. We run a risk as writers, if we’re not careful, to start producing novels that have nothing in them, films that are mostly padding, and episodes that play out more something that would happen between one commercial and the next than a complete episode. It’s hard to imagine, even harder to accept, but the truth remains that we’ve seen some people already try to sell a show on almost nothing happening and only one of the two meant it as a joke.

The other? Some people still don’t know what the hell happened after 121 episodes…

So imagine what that would have looked like if less talented writers wrote it… and understand my fears.

(I write novels. They are in a series and they have a C plot, but each of them is a stand-alone story. I also have a twitter account, there is also a C plot there, but it takes a while in 140 characters.)

I feel completely the opposite: shows are dragging from episode to episode with nothing happening. A whole 13 episode season and you have just the beginning of the beginning of the intrigue…. Like we all have soooo many hours to spend.