The time of year has come once again, the world has turned autumn shades and winter is coming. A season of holidays, ranging from thankful to solemn, now begins to stretch over the dark months. And to open these we celebrate Halloween, the days of the dead, or variants thereof. Long made a family friendly holiday, there was once a time that All Hallows Eve was seen as a very serious and solemn time, marked with a time of worship and reflection that would help the Catholic Church convert the pagans in Northern Europe and give them an opportunity to celebrate their own rituals within the framework of Christianity.

Of course, many people today know of Samhain, the Celtic festival devoted to the time when the veil between this world and the next would be thinner. Every year, you’ll hear at least one person tell you of how Halloween was all based on this one holiday, that the various traditions we’ve lost the meaning to once held an important place in the Celtic celebrations. But few people actually take time to make note of the fact that Samhain was also the celebration of the New Year, a time when one year was coming to an end and the next year was about to begin. And fewer mention the fact that the Celts and Gaels weren’t the only ones with a celebration this time of year.

Because this was also the time of the Norse New Year, the Vetrnætr, the “Winter Nights”…

Out With The Old, In With The New

Despite the fact our current calendar now marks the beginning of a new year in the middle of winter, this wasn’t how things have always been. Cultures throughout Europe based their year on seasons and specific days of the year, such as the solstice. And, while often overlooked, the Samhain celebration was also not just a celebration of the changing of seasons but actually a celebration of the changing of years as well. With the end of harvest and the beginning of winter, the Samhain time was the end of a year’s worth of work and thus an end to the year as far as the people saw it. In fact, one important tradition of the Samhain was to ensure that you completed any unfinished business and could enter the new year with a clean slate. This would be the time you put old problems to rest so that they wouldn’t burden the new year.

But the Celts weren’t the only one to observe this sort of tradition. Even further north in Europe the Norse were celebrating something similar to this: the Vetrnætr, “Winter Nights”. This celebration, lasting for several days and nights, shared much in common with the Samhain but took some aspects even further. Like the Samhain, this was also the time to put to rest old problems and to finish your year’s work. With the harvest coming to an end, the winter about to come, and the world about to get very cold, the Norse were more than happy to have one final hurrah before it became too cold to even think. And so, the Vetrnætr was a time that some have described as essentially the Viking Carnivale – marked with colorful celebrations and revelry.

This was indeed the time when the world was coming closer to death and the barrier between worlds was weakened. But while the Celts saw this as a more passive affair, the Winter Nights were marking a whole other event for the Vikings. At this time, as the seasons were beginning to change, the Wild Hunt would begin. Starting in late October and lasting until the return of spring, the Wild Hunt would be the time of the year where Odin would ride through the lands, hunting for various prey and taking anyone who saw him along on the ride. Together with Odin, these people caught up in the wild hunt would ride at his side as ghostly riders in the sky, lighting up the long winter nights as they crossed the heavens.

To mark this, the Vetrnætr was a time when families would come together to both honor their ancestors and their gods. With the veil between the worlds thinning and Odin about to ride once again, this was both the best time to show their appreciation and commune with the world beyond. To celebrate this, along with their great feasts, this was also a time of sacred rituals. Two of these rituals in particular were sacrifices to be held on specific nights known as “blóts” or “neuters”. These nights were held as sacred times for specific ritual sacrifices, which would both put the old to rest as the Celts did in Samhain, and ensure that the new year would be full of good fortune.

The first of these nights, the Álfablót, was a sacrifice to the elves in a private ceremony held at a family homestead. Waiting for the end of the harvest, when all of the crops had been gathered and the animals were most fat, this sacrifice’s meaning was somewhat shrouded in mystery. Due to the nature of Elves in Norse cosmology, some believe this night to be dedicated to the memory of their ancestors. However, the details of this sacrifice were few and far between because it was held in a very private fashion with only the family invited to attend. In fact, the few stories told of the Álfablót are dedicated to this privacy, with people being warded away from interfering in the family’s time.

What is known is that women were likely the ones to carry out these rites. The Norse had a fairly progressive view of women and saw them as the keeper of the household and the ones who could commune with the world beyond. Norse ceremonies and religious practices were generally carried out by priestesses and, because of this, even the private ceremonies like the Álfablót were likely conducted by the women of the homestead. Along with this, we know that it was a time when Odin may have been invoked, as it was the time when his hunt was to begin, and some ceremonies held in the Vetrnætr were also dedicated to the Valkyrie, who would ride with Odin alongside the others swept up in his wild hunt.

To the Valkyrie, however, a more public ceremony was to be held as well. The Dísablót was a night of public sacrifices dedicated specifically to the female deities of Norse cosmology. The Valkyrie, who were the embodiment of the forces of life and death, were among those honored in these ceremonies – likely to help ensure that the fallen had reached the proper place. But, along with the Valkyrie this was a ceremony held for the likes of Freya as well. Being a goddess of fertility, Freya and others like her were invoked during the Dísablót to bless the work of farmers. Because of this, the ceremony is thought to have been held at two different times. If held at the vernal equinox, this ceremony was to bless the planting and growth of crops to ensure a good harvest. However, when held during the Vetrnaetr it was to serve two functions: to thank the goddesses for having blessed the harvest and/or to ensure that the next years would be just as good or better.

While some stories have identified men of important standing doing the Dísablót, this too was most likely handled by priestesses instead. In fact, outside of the revelry of the three to five day celebration, most things done at this time were carried out by the women of the community. But not all things to be done at this time were handled by priestesses or the woman of the house, some could be done as a personal rite. Of these, the most popular of rites was for a personal divination of the future. While the Celts saw the Samhain as a time to put to rest the year before, the Norse were more interested in looking ahead (as few get through the winters of the far north without a little bit of hope). As such, divination of future events was a popular event at the time, and getting such powers was something thought to be possible for anyone with the fortitude.

Should one want the powers of divination, they needed only to sit on a grave throughout an entire night during the Vetrnætr. This person was then thought to be tormented by various visions and spirits as they made their attempt, many said to be driven to madness. But it was believed that if someone could actually sit through this torment without losing their sanity they would be granted many powers by the experience. Of these, they would gain great insight not only into their own future but the future of others and of their environment – able to predict personal outcomes and possible harvests in the future.

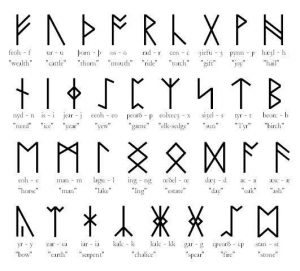

The act itself, considering the belief the Wild Hunt was about to begin, likely derived from Odin himself as his own powers were gained in a similar fashion. Odin’s powers of wisdom, magic, and writing were gained through personal sacrifice or negotiations with other deities. Of these sacrifices, one that Odin was best known for was impaling himself on the World Tree, Yggdrasil, and leaving himself hanging for several days. In the process of hanging there, the knowledge of the tree entered him and gave him the knowledge of Runes, writing, and their true meaning (which was thought to have a magical power).

As a result, the time when the barrier between worlds was thin and Odin was to come must have seemed a perfect time to attempt similar – sitting on a grave rather than hanging from a tree. Probably most telling of this connection was the belief that one of the powers of divination granted to the person was “bardic” power – the gift of story telling and crafting words. To the Norse, words had great power.

And, while being a bard may not seem as “powerful”…

To the Norse, it was a treasured talent.

(I write novels. I also have family who look fairly Nordic. And, I have the power of words – I even spell whole words on twitter. It’s a miracle!)