After relaunching the blog, getting a few cute holiday articles out of the way and getting past one hell of a seasonal health problem, I’m back and ready to dig back into the mythologies of the world.

For those just joining, the premise is simple: our fantasy genre, especially epic fantasy, is determined in large part by the mythologies that originated out of countries touched by the crusades. The dragons and ghouls that grace our pages are essentially just one version of thousands we could be drawing from. So, in an effort to inspire some diversity in the stories we tell, I’ve made a point to start learning about new religions and then take some time to shine a light on the alternatives I’m finding along the way.

As we last left this series, we were deep in the mythologies of the major West African cultures with the Efik and their not so friendly creator deity Abassi, may he never notice humanity has invented the internet. The Efik, as a result of their beliefs, have had some rough relationships with other cultures. And one of the cultures most impacted by the Efik in this region were their neighbors…

The Igbo

Despite proximity to a culture with a god like Abassi, the Igbo people have one of the most mellow outlooks on the world to be seen. Much in the same fashion that many West African cultures mirror the religions of Judeo-Christian origin, the Igbo have parallels to cultures somewhat further east in the likes of Jainism, Hindusim, and Buddhism. According to the Igbo religion, Odinani, humanity’s chief responsibility is to find peace with each other and their surroundings.

Those who follow the Odinani faith are to find spiritual enlightenment through a deep connection with their personal spirits and, in turn, with their Panentheistic god. It is the belief that, while they cannot commune directly with this god, working through their personal spirits, the Chi, will allow them to connect to this god and the universe itself. To achieve this connection they are allowed to take any path that will help them find it, including other religions – a factor which lead to many of them adopting Christianity with little difficulty.

To understand how this works, first we have to start at the top with…

Chukwu

The first thing to understand about Chukwu is that you can’t understand Chukwu. Like a blackhole (and many other supreme gods in the world), you aren’t capable of seeing or conceiving the true nature of Chukwu, only the impact s/he has on the universe. Chukwu is genderless, formless, and as a panentheistic god is unified with the entirety of creation. However, this is not to say that s/he is without any form. Chukwu can be understood, like that previously mentioned blackhole, indirectly through the aspects of Chukwu that permeate the universe.

The first aspect of Chukwu is the concept of “Chukwu” itself – the power of creation and the existence of all things. Chukwu is believed to extend into all of the different elements of the universe and into every spirit, essentially being tied into all things and existing as all things. This is a familiar concept for many other panentheistic religions, including Christianity, and thus it’s easy for the believers of Odinani to adopt new religions and accept that Chukwu can be used as a name for any god they may eventually worship.

The second aspect is Okike, the laws that govern the universe – both visible and invisible. Chukwu is what drives all things, as they are a part of him, and that means that the rules of how the universe works are determined by his actions. These rules and what happens are set in place without his direct interference, allowing him to be an unseen force, essentially giving him control over the world without having to directly interfere in it.

The third aspect is Anyanwu, the sun and the source of all wisdom and knowledge. The believers in Odinani believe that light reveals all things and that Chukwu, through the sun, shines knowledge down on the world. It’s in this guise that Chukwu is believed to be the one who creates all wisdom and distributes it to the people and the spirits.

But from there, Chukwu’s aspects become more intimate with the world of the mortals. First, Chukwu connects to the world through the aspect called Agbala, the fertility of the Earth, and through Agbala we come to the…

Alusi

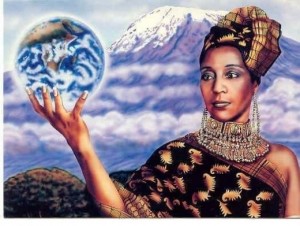

Though known as Agbala when considered an aspect of Chukwu, the Earth itself has a personification of its own by the name of Ala. Ala, the goddess of the Earth, is still an incarnation of Chukwu as well, along with her husband, the god of the sky, Igwe or Amadioha depending on who you ask. But, through Ala, the goddess of fertility and creativity, all other things are born – including the spirits which govern the day to day activities of the world. These spirits, along with Ala, are known as the Alusi.

From an outsider’s perspective, it would seem that the Alusi are “gods” in a pantheon. However, the truth is that each of the Alusi, like all other things, are incarnations of Chukwu, forms which s/he has taken for the sake of taking more direct action in the world s/he created. Essentially, while all things are Chukwu, the parts of Chukwu called the Alusi govern the world in a more intimate fashion than the more abstract force of creation they stemmed from.

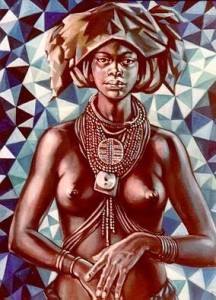

As incarnations of Chukwu, an entity which is formless and unknowable, there is no specific description for what an Alusi may look like. Male, female, visible, invisible, tangible or intangible – the form of an Alusi is determined by what they need to be. Many of them are simply considered the spirit driving the natural elements and thus considered to be made of what they control. Meanwhile others are thought to be more concerned with the actions of the living or the deceased and need to commune with those people as a familiar form. The only thing that they really have in common is that they all stem from Chukwu through Ala, who does have a known form of a loving mother to all things.

As for Ala herself, she is one of the most sacred of the Alusi for many reasons. She is known to be the one who gives birth to all life and spirits, but she is also where all things return when they die. She carries the departed ancestors within her womb, and is thought to be capable of swallowing up those who have wasted their time in the living world. This act of swallowing is because Ala is also the goddess of morality, and a judge of the living and what they have done. Those who commit a great crime are said to have desecrated Ala since the crime was committed while standing on her Earth. She is especially concerned with the protection of women and children as, unlike their neighbors the Efik, the Igbo believe that having many children is a blessing from the powers that be. So those who would bring harm to these people need to be greatly worried of where they tread.

In fact, Ala’s importance spread even to their neighbors, the Efik, as they felt Ala’s judgment and compassion for humanity was a bit more forgiving than that of their gods Abassi and Atai. While Abassi and Atai held judgment of humanity as well, Ala’s treatment of the dead was far more welcoming. On top of this, another thing that was particularly important to all was that Ala was not just a goddess of death, but a goddess of birth as well. Because of this, it was seen by many Efik that the Igbo’s goddess Ala was a more benevolent mother to their people.

And as the mother goddess, Ala was also responsible for giving birth to the spirits which are attached to every living person, spirits which go by the name of…

Chi

The final aspect of Chukwu, Chi, is arguably the most important in Igbo life and religion. While many religions have a dualistic view of human existence (being one part body, one part soul), the Igbo believe that people are made of three parts – body, soul, and Chi. The Chi is a spirit attached to each person as they are born which is given the tasks which they must carry out in life. They are, for all intents and purposes, your destiny.

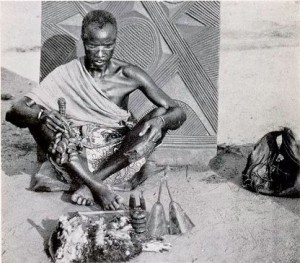

Dealing with your Chi is the most important task of the life of someone who follows Odinani. Your Chi controls not only your destiny in the living world but also your destiny beyond. If someone is not in tune with their Chi, they will often be going down the wrong path. Because of this, it’s important for all believers in Odinani to undergo a spiritual journey through any means necessary to commune with their Chi, identify what it wishes from them, and then do as it wills. This journey can be accomplished in many ways, including other religions, and it is encouraged that believers in Odinani use other faiths in an effort to understand their own place in the world and achieve harmony with it.

The first reason communication with your Chi is so important is that you cannot have a good life without knowing what your Chi wishes from you. It is impossible to act against the will of your Chi successfully, even if you’re attempting to do something “better” than what your Chi would have you do. As a result, any misfortune that befalls you in life is thought to be caused by your Chi being displeased with your actions. If you’re meant to be a simple farmer who takes care of the village but you instead try to become wealthy, your Chi may find ways to ruin your fortunes until you start learning to plant crops. Because of this, communing with the Chi, learning its name and what it wants from you, is an important task for your life on this Earth.

More importantly, in the grand scheme, is the fact that your Chi is also how you are to commune with the spiritual world and achieve what the spiritual world wants from you. According to Odinani, people are incapable of being in harmony with the world around them without help from the Chi, as only their Chi are capable of being in harmony with Alusi and, through them, Chukwu. This task can’t be achieved without the Chi and, as a consequence, failure to meet the demands of your Chi and achieve harmony with it will cause you to have greater misfortune not only in life but in death.

As a person dies and returns to Ala, they are judged by whether they led an honorable life and if they received a proper burial. Those who have lived life according to the desires of their Chi and have carried out an honorable life are then granted the right to join the ancestors, the Ndichie, in the realm of the ancestors. From there, they can keep watch over their people, both their family and their village, and grant the living with the blessings of a good, long life and everything they will need to make that happen. Essentially, by achieving the goals of your Chi, finding harmony with the world around you, and spreading love, harmony, and peace – you go on to continue doing the same for all generations to follow.

While I rarely point out exactly how these religions could be used by a writer to create a solid fantasy story, I feel compelled to point out that this is the first time I’ve seen a religion that has the Hero’s Journey practically built into their fundamental religious beliefs. The Chi, and the need for a person to achieve the goals of their Chi, mean they must take a journey, either spiritually or physically, if they intend to return to the ancestral domain in Ala’s womb. This also means that the Igbo try harder than anything to be a positive force on the world around them and everyone they meet to the best of their abilities. This gives them a generally good outlook on life and make them the kind of people who would go out of their way to achieve something for the greater good.

Because of this, while their neighbors the Efik were known for being somewhat discontent and under the belief that their god chose to punish them with war and death, many Igbo ceremonies and rituals are known to have a more celebratory nature. Common Igbo names have meanings like “a child is worth more than money”, and they believe the generations of the future are a blessing, rather than a curse. They even find women who have had multiple children to be sacred, celebrating their hips, of all things. And, as a result of this outlook on the world, despite some dark events that befell them in the fairly recent past…

The Igbo haven’t lost their ability to party.

(I write novels. Hopefully that’s what my Chi wants me to do, but sometimes the sales figures disagree. I’m sorry Chi!)