In today’s era it’s fairly well established that everyone understands the importance of a suspension of disbelief. Long ago it was a bit less likely that someone would be compelled to stop reading or watching a story in the middle because of their lack of belief. The reason for it is fairly simple: most fiction at one time was thought to reflect the real world and how it works. Even the most fantastic of stories from those eras was, in part, believed to be representative of the world as it was. The earliest plays to feature gods and monsters were telling stories from the religions of the era. Works like Dante’s Inferno were, at the very least, thought to be a theory into what the afterlife might actually have been. And Shakespeare, while pushing some boundaries and making up some shit as he went (particularly words), was generally writing about events that everyone believed could happen – witches included.

So it often gets overlooked that suspension of disbelief, in its current form, is really a fairly new concept in the grand scheme. Sure, there was always a need for the audience to believe irrational behaviors, but the scenarios were generally plausible. This really applied to almost everything, no matter how silly or believable it may sound to us in the modern day. Two families bitterly feuding with each other and tearing young lovers apart? Happens all the time. Zeus getting frisky with a village girl in the shape of a bull? According to the things people used to believe…apparently that happened all the time too. So what we have as “suspension of disbelief” today is not necessarily what they used to have in the days of yore.

And this is a problem for writers and even audiences because that means, at times, it’s hard to gauge just when suspension of disbelief is going to become an issue. It’s especially true in speculative fiction genres that push some limits because we often find that audiences will reject something even after they’ve accepted something far less mundane. We’ve all encountered a situation where someone will believe that a character can fly, but then seemingly become irrationally upset with how believable another element of the story happens to be. As you’ve likely heard before, “you believe that man has superpowers, but this is where you draw the line?”

As far as suspension of disbelief is concerned, you would think that the more ridiculous premise would be the part rejected, not the more mundane aspects. For a long time I couldn’t quite reconcile these concepts myself. But recently something clicked for me that hadn’t in the past as I came to realize that there was something other than suspension of disbelief at play here. Because it’s ostensibly part of the idea of “suspension of disbelief”, it often gets overlooked as being something of a distinct phenomenon. It’s the root cause of those weird moments where someone will believe in a talking dragon but not in a character’s actions.

I call it…

“Bullshit Tolerance”

The thing that had escaped me for a long time is that while people are more than capable of believing seemingly unbelievable things, that may not necessarily mean they accept it. Though it seems like those two things would be the same, they’re actually quite different when you really stop to consider. The ability to believe something is the ability to reconcile whether or not it makes sense, whether you can find it reasonable and logical (even if not everyone may agree). On the other hand, acceptance is not about what you are able to reconcile but rather about how you feel about it. Suspension of disbelief, as it says on the tin, is all about what people are willing to believe while “bullshit tolerance” is about what you’re willing to accept – and that’s exactly where the line appears.

When someone’s sitting to read a comic, play a game, watch a movie or lounge around with a book, they’re going to make a choice about whether or not they buy into the premise of that world. Provided you’re willing to believe that premise, suspension of disbelief is all about whether or not something makes sense within that specific world. If the world says that it’s possible for people to fly, so long as it keeps that rule consistent, you’ll believe it as far as it pertains to that story. Whatever hand-waves or magical nonsense has to be provided to make that click, it’s still an exercise in logic and reason. You will learn those rules, see what is happening, and judge the events based on the rules as you understand them. But sometimes something that makes sense can still be unacceptable. Case in point: the real world.

Look around and you will find a lot of real world examples of people having hit a bullshit tolerance in their real world lives. In fact, though I use an example from the most recent election cycle, every major national election has a touch of this. The losing party, regardless of who it may be, will generally be up in arms about the legitimacy of the winning party’s victory. Though people can understand that it’s really happening and know that the unpleasant situation for them is still reality, that doesn’t necessarily mean they accept it. For whatever reason, while they are perfectly capable and willing to understand what has happened and believe it has happened, the event in question has not only subverted their expectations but gone completely counter to them. In fact, often, these outcomes derail the very reason these people were invested in the situation in the first place. And, while it may feel silly to make such comparisons to fiction – it is exactly the same phenomenon.

This event above, from Man of Steel, was a line that a lot of people couldn’t tolerate crossing. It was the point where a lot of people asked that question: “you believe a man can fly, but that’s where you draw the line?”

They were willing to believe that a man could fly, but they weren’t willing to accept that man was capable of certain violent acts. Some responded to this by pointing out that Superman had killed in previous incarnations, sometimes quite openly. Some had even pointed out that the no killing rule was something Batman had imposed on himself, not Superman. But no amount of logic, reason, or evidence could make that lack of acceptance go away because it wasn’t about understanding the event but rather the feeling. People know that Superman is capable snapping someone’s neck, they are even capable of understanding why he would do it. But, years ago, when people had a fit over the action happening they were demonstrating an emotional attachment to the idea that he wouldn’t. And that’s bullshit tolerance, because bullshit is completely believable but will always be “bullshit”.

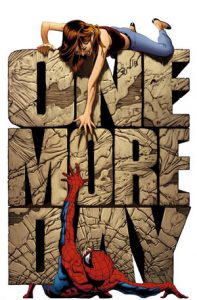

Think about it: while you use the phrase “bullshit” for things that you don’t believe, or jokingly about something you know isn’t actually true, you’re more likely to use it for things that you don’t want to believe. Your insurance rates are skyrocketing? That’s bullshit. You got a flat tire on the way to work after getting new ones? That’s bullshit. Sherlock Holmes falls to his death while fighting Moriarty? Bullshit. Spider-man traded his marriage with Mary Jane to Mephisto to save Aunt May from a bullet wound that even Doctor Strange somehow couldn’t fix?

And when you really think about it, these are the more dangerous breaches of “believability” than your average issue with suspension of disbelief. Someone lacking suspension of disbelief will put down the book or turn off the TV before you’ve even had a chance to make them truly invested. But these events, the moment where you violate a person’s bullshit tolerance, that’s where an emotional reaction is most likely to arise. Someone who doesn’t believe your story is going to brush it off because it’s not real or important to them. But someone who has been reeled in and has become invested enough to scream “bullshit” at their screen or the book in their hands is invested enough to reject you violently. In the gaming community this is what we would call a “rage-quit”.

The real trick for creators is to create something that will make someone invested enough to care but not so invested as to become upset if it goes the wrong direction. It’s not something you can really determine in abstract because it’s not about logic. Each person’s bullshit tolerance is subjective, determined entirely by their emotions and their state of mind. And, unfortunately, that means it’s true when people say that it’s impossible to please everyone. Instead you have to find a happy middle ground between the story you want to tell and how far most people are willing to go with you.

This means understanding your audience, first and foremost. Though even audiences are made of individuals and everyone will be just as subjective within, the fact they’re united around a single interest will usually give you a chance to make some assumptions. And, if they share the one interest, usually you can track it back to other interests and places where they shared those interests. If you’re a beginning writer it’s pretty likely you’re going to find an audience within an already established fandom for someone else. This is a good thing, because it means that you can study that audience and see where their bullshit tolerances may currently lie. Though such readings aren’t perfect, trying to understand your audience in any fashion will give you some idea on just where their threshold for bullshit actually lies. Fandoms generally create a pretty complex picture of what their average member is really like if you take in enough of it. And, regardless of how incomplete that picture may actually be, if you look closely enough…

You’ll probably see some signs on where they stand with “bullshit”.

(I write novels full of unbelievable things. I also tweet, feel free to call me on my bullshit over there.)